04 Dec In the tsunami of media tech, which tools do you need and how should you use them?

There are more shiny new things to distract you than ever before. Figure out which ones help you meet your readers’ needs, and double down on those alone.

Prepare to be overwhelmed. Again.

In the “good old days”, we could go for decades without a disruptive new technology. Think about vinyl records: Introduced in 1888, they were undisrupted for almost 80 years until cassette tapes came along in 1963. Cassettes enjoyed almost two decades without disruption until CDs arrived in 1981.

Today, we have new audio technologies pop- ping up every time we turn around. Consumers can get music on desktops, laptops, smart phones, headphones, tablets and voice-activated personal assistants either by downloading or streaming or just saying to your so-called smart speaker: “Hey, Siri, play Beyoncé’s ‘If I Were a Boy’”…

And that’s just music.

Tech in media now includes:

• Augmented reality

• Virtual reality

• 360-degree photos and videos

• Messaging apps

• Artificial intelligence

• Chatbots

• Device graphs

• Sophisticated analytics

• Beacons

• Group collaboration tools

• Automatic content creation tools

• Micropayments

• Voice-activated personal assistants

• Sophisticated content management systems

And just over the horizon are some media tech you may not have even heard of yet (look’ em up and get ahead of the game!):

• Volumetric displays

• Gesture-controlled devices

• Affective computing

• Personal analytics

• 4D printing

• Smart data discovery

What’s a media company to do?

Well, certainly not embrace every shiny new thing that comes down the road.

There are certainly plenty of hot new things to tempt you. And plenty of so-called experts predicting the sure-thing future of each.

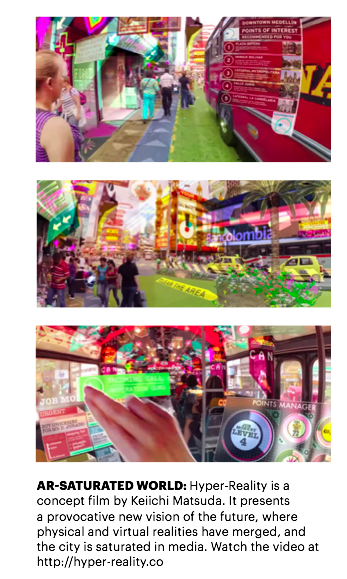

Virtual reality seems to be this year’s darling, with its proponents conveniently ignoring the staggering costs and equally staggering low numbers of adopters. Google glasses are back, but in the guise of Snap Spectacles. Is second time round the charm? Everyone’s talking about messaging apps and chat bots.

There is already a wide array of new technologies offering media companies new formats and platforms for delivering content.

“Media have spread to an array of internet-connected devices for the home, car and other personal spaces,” wrote Zach Seward, senior VP/ product and executive editor at Quartz. “These are taking the form of messaging applications, voice interfaces, smart gadgets and other technologies that personalise your experience based on context.

“Some of these platforms are already huge: messaging apps such as Slack, Skype, WeChat, Kik, and Facebook Messenger; and digital assistants such as Alexa, Siri, Cortana and Google Assistant,” Seward wrote on the Knight Journalism Foundation blog.

“At the heart of this new era are two broad fields: bots and artificial intelligence. Bots are software you can talk to… And chatting with a bot… requires a level of smarts that has come to be known as AI [artificial intelligence]. That includes more specific fields such as natural language processing (to understand human input), machine learning (to personalise based on user behaviour), and information processing (to glean insights from large data sets).”

To digest all this and have it make sense for your media company, you first need to step back and decide exactly who your target audience is. That might sound insulting (“Of course we know who are audience is!”) but I am constantly amazed by how many media executives and editors we consult with who cannot describe plainly and precisely in a sentence or two who their audience is!

Second, figure out what types of information your audience wants, where they look for it, and at what hours of the day they consume it. Then, and only then, are you ready to choose the tech tools that make sense for you given what you’ve discovered about your audience.

Because no two media companies are alike, we cannot prescribe a single course of action for tech. Instead, we offer below a smorgasbord of options. The categories and examples of new technology covered in the rest of this story are not even close to being exhaustive. You could write a book about each. Instead my aim is to inspire and provoke your curiosity, giving you enough information to make a decision to pass or to explore further on your own.

1) Advertising tech

In a troubled industry, perhaps the most troubled sector in need of assistance is advertising. Ad blocking, ad fraud, industry dominance by Google and Facebook, abysmal click-through rates (CTRs), and viewability all plague every media company.

Ad tech itself is in trouble with too many platforms, too much data, no consolidation, under-performance, misinterpretation and misuse of data, and a daunting difficulty of use.

Chris Altchek, chief executive at digital publisher Mic, told the Wall Street Journal that their frustration with ad tech has led them to not use “any programmatic whatsoever”, relying instead on traditional sales strategies. Others, like BuzzFeed, are putting all of their revenue eggs in the native ad basket.

But one media company, the Washington Post, has decided that the way to solve the ad tech problem was to build a better mousetrap themselves. And then sell it to other frustrated media companies.

To date, their SaaS (Software as a Service) arm, Arc Publishing, offers 18 products that can be licensed.

“We can no longer rely on partners or vendors to solve problems that are so core to our business,” Arc head of ad product technology Jarrod Dicker told WAN-IFRA. “Right now, the way advertising works isn’t as efficient as it could possibly be, and the mentality has been, ‘Well, that’s just how it is.’”

But that’s not how it should be, nor will readers tolerate it. With Facebook Instant Articles and Google Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP), readers are getting accustomed to speedy load times. “If users aren’t going to wait more than four hundred milliseconds for content, why would they ever wait for an ad?” asked Dicker.

While media companies have worked on improving editorial load times, Dicker said less attention has been given to improving the ads that bring in the revenue.

Decker’s team created a tool to solve that problem. Called Zeus and released in the fall of 2016, it dramatically speeds up page-loading times by employing different loading and caching techniques for third-party programmatic display ads. Decker claims to have achieved a “75 per cent decrease in latency.” Zeus uses both “lazy loading” and software that will reject all programmatic ads that are too data-heavy.

“We can talk to an [ad] partner and say, ‘This is how fast our content is, and your tech is slowing things down,’” Dicker told AdExchanger. “Now that we are actually doing it, partners are coming to us with solutions.”

“We focused not just on improving speed, but also producing a scalable product that could help solve problems for industry wide issues like viewability, ad fraud and ad blocking, and we’re excited to offer this technology to other publishers as well.”

Zeus also offers:

• Smart scrolling protection: ad call and rendering based on swiping behaviour

• Heavy ad protection: real-time log of creative size to optimise delivery based on weight

• Prioritised loading: ad delivery is prioritised based on viewability

• Predictive viewport loading: creatives load based on viewport to eliminate fraud and extraneous background script loads

• Intelligent caching

“Zeus has improved our advertising performance exponentially in both viewability and engagement,” Dicker told AdExchanger.

But Zeus only solves problems with programmatic advertisers.

What about ads sold in-house?

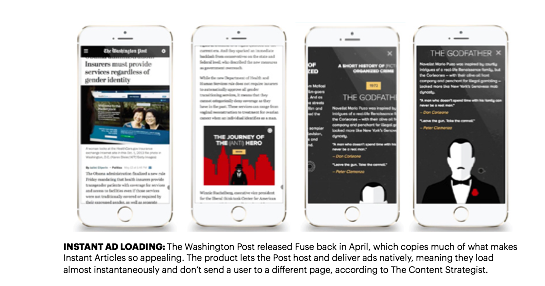

Enter Fuse. Launched by the Washington Post in April 2016, Fuse is a tool that enables the hosting and delivery of ads natively so that the ads load instantly instead of forcing the user’s device to go elsewhere to be served the ad. Another ad tool, Prism, was launched by the Post back in 2013 and was developed as an integration into the CMS, not as a separate entity, like many ad servers. Ads load at the same time as content, resulting in an uninterrupted user experience.

Other media companies, including Vox, BuzzFeed, and the New York Times, are also taking the DIY approach and building their own ad tech tools, but they have yet to license their software to others.Here’s one last ad tech tool to consider: a device graph.

A what?

Because cookies don’t work on mobile devices, it has been a challenge to track users across devices. As a result, the impact of mobile ads has been hard to gauge. A device graph is a map that solves the identity management problem. It links individual people to all the devices they use, from their office computer to their laptop to their mobile device. So, instead of counting each device as a different person, media companies and advertisers can track an individual’s total media behaviour, eliminating duplication.

With a device graph, an advertiser can see what time and on what device a user was ex- posed to their ad, assisting in determining, for example, the role a mobile ad had on an action such as a purchase.

Device graphs come in two flavours: deterministic and probabalistic. Media companies and advertisers need both. Deterministic device graphs look at log-in data like Facebook can do, as well as situations when users are asked to enter their email addresses. Probabalistic graphs employ location data to match devices to individuals.

“Some vendors claim they get around 80 per cent accuracy on this,” ZenithOptimedia head of data and ad tech Samir Shah told Digiday. “It used to be 40 per cent.”

The benefit to both publishers and advertisers is clear: If advertisers get proof of an ad’s contribution to a desired action, they’ll buy more advertising. “The CPM on mobile isn’t low because of the ad format; it’s because of the tracking. If buyers can link the value of mobile to the overall path to purchase, the price should go up,” Adform’s chief strategy officer Anthony Rhind told Digiday.

The only fly in the ointment is device sharing. Presently there is no way to detect if a son or daughter is using their parent’s home computer or smartphone. But most media execs and advertisers should be happy with 80 per cent accuracy after living with far less.

2) Analytics

To paraphrase an aphorism, you can’t improve what you can’t measure and interpret.

And we already are measuring almost everything about magazine media. No one complains about having too little data. But many media companies don’t know how best to analyse their data and use the conclusions in planning and publishing content and advertising.

“There is much more to editorial analytics than big screens with numbers that go up and down,” Federica Cherubini, the co-author of the Reuters Institute 2016 Editorial Analytics Report, told NewsWhip.com.

“Tools are, of course, the first step. But even with the best available tools and a strong analytics team, a newsroom that doesn’t underpin those with a culture of data use will fail to realise its full potential. Equally, a newsroom can have good tools and a culture of data, but with no in-house analytics expertise it will struggle to do in-depth analysis and use analytics systematically.”

Data analytics software has been around for a long time. Everyone uses Google Analytics or Chartbeat and many use KissMetrics, Omniture, ComScore, NewsWhip, or parse.ly. Some media companies, frustrated with the limitations of off-the-shelf software, have created their own tools.

But even at media companies using the analytics tools, most editorial departments just receive raw numbers reporting individual metrics (page views, unique visitors, etc.). Editors and reporters do not receive any sophisticated analysis of what the data mean and how to use them for everything from story selection and presentation to publication timing and platforms.

“A monitoring of performances and achievements is indeed happening, often in the form of periodical or even daily emails, but these numbers rarely inform editorial decision-making,” according to the Reuters Institute 2016 Editorial Analytics Report. “They are numbers without meaning and without consequences. Short-term day-to-day optimisation of articles on the homepage and posts on social media are not uncommon, but there is less longer-term strategic use of data to shape editorial priorities and underpin organisational objectives.

“When this occurs, it often stays within the team handling the job (often not in the news- room) and is not spread across departments and the whole newsroom,” the report continued. “The kind of ‘democratisation of data’ associated with open and user-friendly dashboards like Ophan [The Guardian’s proprietary data analytics tool] or clearly communicated metrics like Die Welt’s article score are rarely found in organisations with a more generic or rudimentary approach to analytics.

“If data are taken seriously as one of several factors informing decision-making, evaluations of performance, and the development of work- flows and new editorial products, the culture does underpin editorial analytics,” concluded the report’s authors.

Two media companies, Die Welt in Germany and The Guardian in the UK, have created their own data analytics tools, both of which de-emphasise clicks and reward engagement and social shares.

At German daily newspaper Die Welt, the system looks at six data metrics to come up with an Article Score (the name of the system). The six measures are: pageviews, time spent on the article page, video views, social shares, bounce rate, and how many subscribers the article generated.

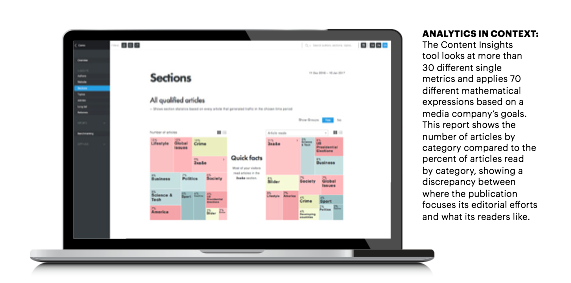

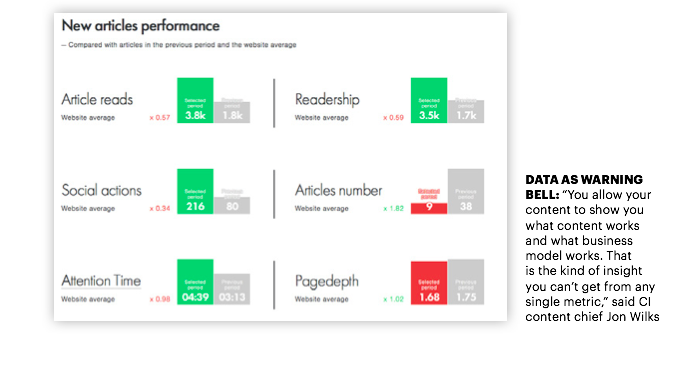

An analytics company, Content Insights (CI), built by former journalists, takes the process to the next level. Like Die Welt’s Article Score, CI looks at multiple metrics, but CI goes well beyond Die Welt’s six metrics and considers the relations between more than thirty different single metrics. Then, CI goes even further and applies 70 different mathematical expressions based on a media company’s goals. The algorithm is called the Content Performance Indicator (CPI). The result is a score that reflects true engagement, and loyalty, and helps writers and editors with short and long-term editorial strategy.

“We are strictly against a single metric as a descriptor of human behaviour,” CI founder and CEO Dejan Nikolić told me. “The idea that ‘returning visits’ equals loyalty couldn’t be further from the truth. It’s not even close.”

Over the last decade or so, data analytics and media companies have been “relying on a different metric and they keep changing the metric, proving each time that it didn’t really work,” said Nikolić. “We went with a ‘no-no’ in the world of analytics – we decided to use many metrics as an index. We collect a bucket of metrics and sort them out by the behaviours they describe. “Why? Because what counts is the relation- ship between metrics – that is what is actionable and describes behaviour,” Nikolić said. “That is the eureka moment!”

“So, we take clickstream and social metrics and look into the relationships between them and then weigh them and score them according to what is important to the website or publication,” he said.

“The result is an indication of how well con- tent is performing relative to the goals of the website or pub,” he said.

“The leading data analytics systems – Google Analytics and Omniture – were both set up by marketers,” Nikolić said. “They show the sales funnel and conversion journey, but if you are trying to judge editorial performance, they’re not as useful.”

What most existing analytics services do is “overstate the importance of real-time analytics, which — to a journalist — is like a cross between seeing their name up in Beatles-sized lights whilst at the same time being offered a free smorgasbord of class-A drugs,” said CI content chief Jon Wilks. “Sure, they get to delight in how wonderfully their latest piece is doing, but that horribly addictive adrenalin hit will be short-lived and leaves them wondering which of their journalistic values they have to flog in order to get more of the same.”

Real-time analytics “tend to confirm a strategy rather than inform it,” Wilks said. “This ‘confirmation bias’, as we call it, shows only that what you’ve created has had some form of instant effect, and highlights the platform that your audience tends to be arriving from – both of interest in the short-term, but unlikely to give you much in the way of insight that could be used to build a long-term strategy. What real-time analytics do very well is encourage the pursuit of clickbait.”

CI wants to move editorial analytics from the largely decorative screens on the walls celebrating the momentary success of a story to the editorial meeting rooms to inform the discus- sion of short- and long-term editorial strategy. “The major breakthrough is [giving editors the] bigger picture so that your audience and content are allowed to drive your business model,” Wilks said. “You allow your content to show you what content works and what business model works. That is the kind of insight you can’t get from any single metric.

‘We need to be measuring content with more editorially-focused tools and measurements – we need to move away from vanity metrics and get a lot better at knowing what action to take when the analytics point to problems,” said Wilks. “Editorial analytics are at their most useful when sounding alarm bells rather than massaging your ego.”

“Our goal is to save editors and reporters time and provide them what they need,” said Nikolić. “We help editors integrate our product in daily workflows and understand and know how to act on the results. We don’t offer conclusions; we don’t want to replace editors, but just lower a bit the reliance on gut feelings in decisions.

“The CI mission is to give editors and reporters critical strategic information and analysis in a tight, quickly and easily digested package so they can learn from it and get back to their real jobs of creating great content,” he said.

3) AI

AI, or artificial intelligence, burst onto the media’s radar in 2016 with a sudden frenzy of chatbot launches.

Perhaps the most pivotal event came in the spring when Facebook announced it was allowing developers to create chatbots for their brands or services to enable consumers to conduct some of their daily activities from within the Facebook messaging platform.

After that, it seemed that everyone was launching a chatbot: Pizza Hut, Sephora, UPS, Lufthansa, Nordstrom, Starbucks, the NBA, MasterCard, and even the White House.

There is even a chatbot to help drivers contest parking tickets in the US: “DoNotPay”. Of the 250,000 drivers who used the bot, the AI “lawyer” won 160,000 cases, a success rate of 64 per cent appealing more than US$4m of parking tickets.

Not to be left out of the party, media sites also launched chatbots, and we cover those in depth in our chapter on Messaging Apps and Chatbots elsewhere in this book. In addition to chatbots, artificial intelligence has other impacts in the media world.

Some media companies, such as the Associated Press, are using machine learning and natural language generation to actually “write” stories. They focus on stories (think sports matches and quarterly and annual financial reports) where data provide enough elements from which to craft a story.

On the ad side, artificial intelligence can be employed to learn about reader behaviour, using first-party and third-party data to, for example, pinpoint where a reader is in the buying process, and learn how to deliver the personalised messages and ads.

On the editorial side, AI can be used to maximise the leveraging of content.

One editorial function that has bedevilled editors and writers for a long time is tagging. In the course of writing, tagging slows the process. After the fact, it’s time-consuming and expensive to take a reporter’s time to do the tedious tagging work.

And yet, tags enable media to do almost everything that happens to a story: how search engines index the site, how related content is recommended, how ads are targeted, and much more.

To address this challenge, The New York Times created a platform called ‘editor’ that uses machine learning to identify and categorise elements of a story in real time as the story is being written. Where a human editor would feel rushed and tag just a few names and places, this AI-enabled system delivers, in the blink of an eye, fine-grained annotation and tagging to a degree a human could rarely replicate.

The system can identify people, places, events, and more, and it learns the difference between proper names of people and, say, institutions of the same name (e.g., president George Washington and Washington University).

By annotating and tagging various components of a story, it enables a media company to do so much more with that information,” according to a NYT spokesperson. “New devices, especially those with smaller screens, could make use of smaller chunks of content.”

Watch the Editor tool in action on Vimeo.

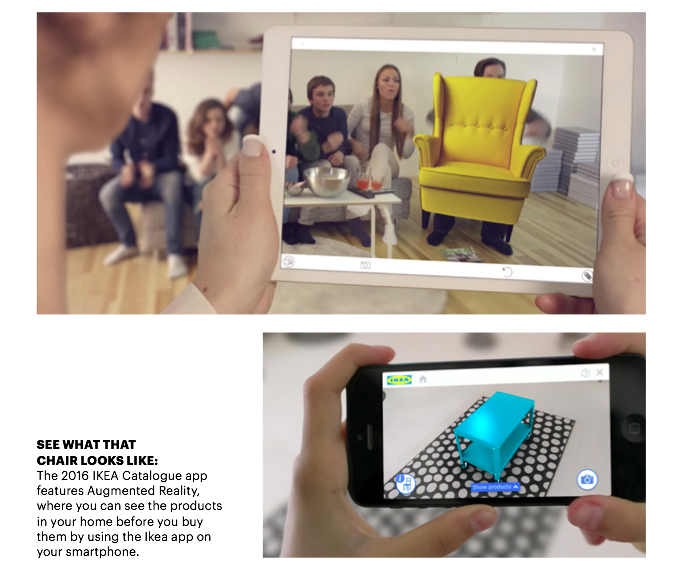

4) Augmented Reality

How often has one year’s “next big thing” turned out to not be quite ready for prime time? Over and over again.

For at least the last seven years or so, augmented reality (AR) has been a regular member of the club for still-not-ready-for-prime-time “next big things”.

AR has actually been around since 1968 when MIT scientist Ivan Sutherland created the Sword of Damocles, the first AR headset. Advances in AR tech proceeded from there, including a US Air Force device built in 1992 to enable military personnel to virtually control and guide machinery, and in 1994 an AR theatre production featured acrobats dancing in and around virtual objects.

In media, the first big AR event was Esquire Magazine’s 2009 cover that came to life when readers scanned it, causing Robert Downey Jr. to pop out of the page along with a lot of other special effects.

Since then, AR has made a regular appearance on those New Year’s lists of things to watch for in the coming year.

In 2016, AR made a huge and global splash with Pokémon GO. “Pokémon GO created more awareness of augmented reality,” Rachel Pasqua, connected life lead at media agency MEC Global, told AdExchanger. In 2016, investments in AR and VR (virtual reality) exploded to reach US$1.1 billion, according to Augment, an AR app developer.

And more and more companies are employing AR in print campaigns.

Elle

The November 2016 issue of Elle issue included eight covers, each one featuring an actress (Aja Naomi King, Amy Adams, Anna Kendrick, Felicity Jones, Helen Mirren, Kathy Bates, Kristen Stewart, and Lupita Nyong’o). When readers logged into the ElleNow app and held their mobile device over each cover, they were treated to video interviews with each actress.

“Everybody has a better understanding of AR because of Snapchat and Pokémon Go,” said RYOT co-founder and chief executive officer Bryn Mooser, who noted the ease of AR via mobile as opposed to virtual reality. “VR is really a headset experience that transports people… augmented reality, or mixed reality, is about overlays.”

Others

Media weren’t the only AR players in 2016.

Brands were even more active than media. Lego’s AR app caused cool jets and trucks to pop out of a page and drive or fly around. Blippar enabled users to get nutritional information about fruits and vegetables just by pointing an AR-enabled mobile device at the object.

Movie theatres enabled passersby to watch trailers when they walked by a billboard outside the theatre. The Quiver children’s colouring app brought the kids’ drawings to life with animated characters crawling or flying out of their drawings. The Magic Mirror app allowed customers to try on outfits virtually. Domestic lighting company Eglo’s AR app let catalogue shoppers place their wares around their home to see what they’d look like. The list is almost endless.

Nonetheless, “AR will remain a cool outlier or a one-off until the experience becomes part of something people do on a regular basis,” digital marketing company Matomy Group CTO Ido Pollak told AdExchanger. “Phones already have the computing power they need,” Pollak said. “Now we just need the applications.”

AR needs to transition from “being a fun little toy and start becoming mainstream,” said Brunno Attorre, the co-founder and CTO of video monetisation platform Uru, in a conversation with AdExchanger. But “it’s like VR right now, more talk than action, and that’s true for everyone, not just us,” Pasqua said.

The mainstream application of AR that will catapult it to a scalable, monetisable tool for media will not revolve around gaming but around something like augmented search, content discovery, maps, navigation or conference calling – a “killer app” that anyone could use, Attorre said.

Until then, monetisation is not realistic.

“There needs to be enough content and variety of content and experiences in order to be perceived as more than just a one-off,” Pasqua said. “Right now, most people experience AR through Pokémon GO or Snapchat.” “We are having some discussions about AR content in ads, but the real promise is as a search and information delivery tool,” she said.

“AR is definitely going to be huge, as is VR, but scale is an issue here,” Matomy’s Pollak said. “For programmatic, you need scale, and until you can mass-produce AR content, that won’t happen.”

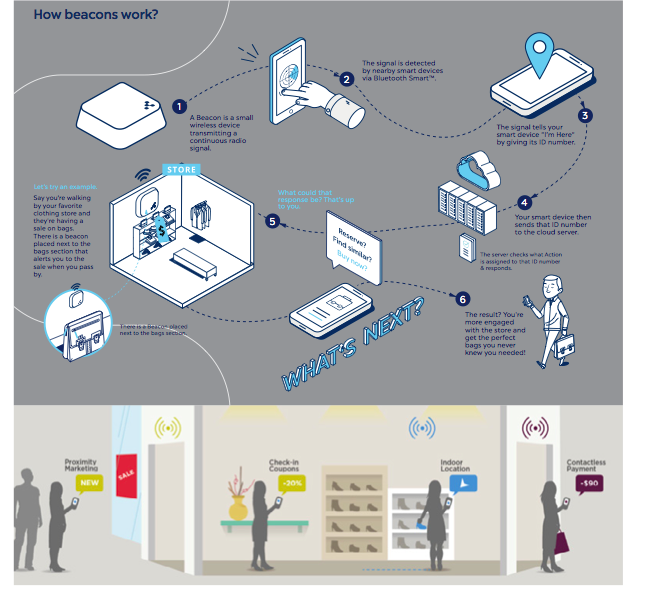

5) Beacons

Like augmented reality, beacons have been around for quite a while but they, too, are another tech predicted to break out in 2017.

Also like AR, however, that prediction might be premature.

“Beacons are small wireless sensors that transmit data to phones using Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE),” wrote Brian Friedman, chief technology officer (CTO) of Loopd, an event engagement management company, on the company blog. “They are a popular choice because of their ubiquitous reach, as most all mobile phones have this capability. With a wireless coverage range of 50 meters, beacons can target broad areas at a relatively low cost.

“They are ideal tools for broadcasting general information to a large audience,” wrote Friedman.

“Beacons can push coupons and promotions and also incorporate personalised messages and recommendations based on geography and/or customer purchase history.” However, there’s one big caveat regarding beacons: Media and marketers must use them respectfully. Aggressive over-use, crass pro- motion, or not making notifications an opt-in/ opt-out choice turns off consumers who might feel they are an annoying invasion of privacy. The first beacon tech was developed by an Australian company called “Daelibs” in 2011, but didn’t appeared on the radar screens of the general public until the introduction of Apple’s iBeacon in 2013.

Think of beacons as sort of like QR codes that don’t require the user to do anything. Beacons are like QR codes that don’t suck,” David Helms, CTO of Radius Networks, told PrintMediaCentre.com.

The bluetooth beacon market is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 307.2 per cent from 2015-2020, according to TechNavio.com. About 80,000 units were shipped in 2015, and this number is expected to skyrocket to 88.29 million units by 2020.

And they are being put to creative use by more and more media and marketing companies.

In late 2015, Elle magazine launched a five-week beacon campaign called “Shop Now” that made its editors’ product picks available to users of the ShopAdvisor and RetailMeNot apps. Any of the 25 million users of both apps who had opted to get push notifications would get one whenever they were within a mile of a Guess, Barnes & Noble, Vince Camuto, or Levi’s store, telling them that one of Elle’s recommended products was available nearby.

When readers opened the notification and entered the store, they’d get yet another push notification with a promotion, such as $25 off their same-day Camuto purchase.

To make the experience even more personal, Elle used data to make sure readers got notifications that meant something to them. Using data about readers’ previous activities, Elle was able to avoid blasting the same notifications out to every phone but instead crafted the notice to fit the user. If, for example, a reader had read an Elle story about a Vince Camuto bag, the app told the reader when their coveted bag was just around the corner.

“The single, most universal request I hear from every advertiser, whether it’s luxury, beauty or fast fashion, is, ‘Help us drive retail store traffic,’” Kevin O’Malley, Elle’s senior VP and publisher, told Digiday.

The campaign drove 500,000 store visits in just five weeks, according to O’Malley. The open rate was 15 times higher than the mobile advertising average of 0.8 per cent. In-store visit rates were 100 times higher, according to ShopAdvisor.

Beacon messages do not have a high open rate (perhaps because too many of them are unrewarding, annoying, sales pitches). But the Elle campaign had stunning open rates compared to the average. In 2015, beacon messages had an average 1 per cent open rate, according to a 2015 study by Deloitte. By contrast, the Elle campaign had open rates ranging from 4.8 per cent to 10.5 per cent. Of those who opened the messages, 20 per cent went into stores.

“The results were so good because of how we wired it all together,” ShopAdvisor founder and CEO Scott Cooper told Digiday “When you get an alert from your favourite magazine that’s endorsing something nearby, you walk in the store and get an offer, it’s a really high-quality, curated, exclusive experience.”

“We already curate product in our magazines, but this gets it to the reader when they’re out in the market,” said O’Malley. “That editorial endorsement is highly valuable, because when someone gets a pop-up from a brand sell- ing something, the instinct is delete, delete, delete.”

“Elle crushed open rates, engagement, and revenue expectations,” wrote Hannah Augur, content manager for information technology and services company kontakt.io.

Elle did not get a share of the revenue of products sold. With results like that, more and more media companies and advertisers should be looking to beacons for another way of adding value to their consumers’ experience.

6) Content Creation & Management Tech

If there is any category within media tech that merits encyclopaedic treatment, it’s content creation and management tech.

But we have limited space, so we’re going to look at three topics:

1. Content leveraging

2. Multi-platform sharing

3. Content creation tools

Content leveraging

Every content creator would like to get the most out of each piece of content, but most stories or packages run once and fall off the radar. All that time, effort, and money for a one-shot chance at attracting readers. Writers would like more exposure; the business side would like to extract more value.

Three French journalists have come up with a technology that uses artificial intelligence linguistic analysis and a new way of viewing how content is structured to extend the life of every piece of content. The Storyzy software scans stories and ex- tracts quotes from key people in the story. The tool repackages these quotes to automatically create a whole new selection of quality content, optimised for search and monetisable.

Why quotes? “Quotes express opinions and points of view, they are also short and encapsulate a news story,” Storyzy CEO Stan Motte told HackersMedia.

On average, Storyzy claims the software can generate up to 40 per cent net new content – and a similar percentage of net new revenues.

“From a set-up perspective, we can get publishers up and running and generating new content and revenues within three weeks – with no technical development on their side (as Storyzy hosts the pages),” Storyzy CTO Ramon Ruti told HackersMedia. “Our technology works 24/7 processing both the new flow of articles and also article archives.

“Our solution is designed to help publishers scale their audience reach, with 22 per cent more pages on average generated, recirculate content, and improve SEO,” Motte said. “With an increase in traffic comes an increase in revenue, and we share ad revenues on these new pages.”

Multi-platform sharing

There are some people in media companies who hate the idea of publishing on multiple platforms.

You might guess it would be the journalists, sceptical of the value of “giving away” content to platforms like Facebook’s Instant Articles and Google’s Advanced Mobile Pages.

But you’d be wrong.

Yes, some editorial folks don’t like the idea, but almost ALL developers hate it. Why? Every new platform has unique requirements, and as media companies look to publish on more platforms, the workloads and headaches pile up for the IT team.

A group of developers at women’s site Bustle decided to stop bitching and start fixing. They created Mobiledoc, an open-source article for- mat designed to make it easier for media companies to push their content to new formats and platforms. Mobiledoc is so flexible across so many platforms because it stores only the content of posts, not the design.

Beyond portability, Mobiledoc also allows for the creation and embedding of multimedia elements.

Content creation tools

Again, the universe of tech tools for creating digital content is beyond huge, but here’s a sampling from two digital natives. Writing on TopRankMarketer, content creator and strategist Miranda Miller listed these tools as among her most important:

Ubersuggest

Ubersuggest takes your word or phrase and scrapes Google Suggestions to offer the hottest related topics people are searching for, wrote Miller.

Audacity

Use Audacity to record interviews and edit audio, recommended Miller. Audacity is free and you’ll need a plug-in called Lame to convert their audio files to mp3 if you want to share your interviews in social channels.

Social Search Engine Topsy

Topsy takes whatever keyword or phrase you give it and analyses the social web in real-time. This is a great tool for finding opportunities to create content around questions people are asking, or to address specific issues people want to know about. If it’s happening on the social web, Topsy can find it.

Zemanta

Not big on research? Zemanta will bring images, articles and other web content to you as you write your content into WordPress or Blogger, wrote Miller. As you write, Zemanta will suggest relevant content from your own blog, around the web and their advertisers to inform and complement your piece.

SocialMention

A critical tool for social content creation. What are people saying about your company/industry? They won’t always tag you to alert you. SocialMention analyses sentiment and shows the top related keywords and hashtags, the most popular platforms where related conversations happen, and even the users who discuss it most, suggested Miller.

Here are some tech tools to help create info-graphics and quizzes from Alex Navarro, the senior content marketing strategist at information technology and services company Distribion writing for the Social Media Examiner.

Easel.ly

Easel.ly lets you easily edit and customise infographic templates, wrote Navarro. You can share your new canvas immediately on Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest.

Piktochart

Piktochart lets you create innovative, design-intricate infographics complete with icons, images, charts, and interactive maps, wrote Navarro. Once finished, save and publish directly to Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and YouTube, and even convert long-form infographics to multi-slide presentations on SlideShare.

Canva

With Canva, you can quickly create infographics, along with presentation covers, social media images, online advertisements, flyers, and more, according to Navarro. Canva lets you share your work on Facebook and Twitter.

Visme

With Visme, you can easily create beautiful

presentations, infographics, reports, web content, and wireframes all in one place, wrote Navarro. Share your content online as a URL or on social media, embed it on your website, or download it for offline use.

Quizworks

With Quizworks, you can choose from multiple question types, view statistics, and get access to sharing tools for Facebook and Twitter, wrote Navarro.

Playbuzz

Playbuzz is a digital publishing platform where you can create content and embed quizzes directly on your website. Playbuzz is one of BuzzFeed’s biggest competitors. Just as with BuzzFeed, Playbuzz lets you share your content on practically every device and network, wrote Navarro.

Qzzr

Qzzr is an exciting tool that lets you create personalised quizzes based on your web- site’s look, feel, and language, according to Navarro. Qzzr’s sharing capabilities include Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. You can also embed code directly to your blog or website.

7) Email tech

What passes for “technology” today in personalising emails from a media company to its readers is not really technology at all but just a few clicks: Readers either choose which topical newsletters they want, or which topics within a general newsletter. That’s it.

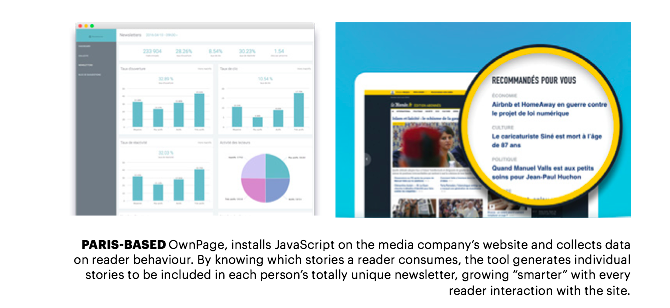

A French start-up has created tech tools that deliver individualised newsletters. Literally -no two newsletters are alike.The startup, Paris-based OwnPage, installs JavaScript on the media company’s website and collects data on reader behaviour. By knowing which stories a reader consumes, the tool generates individual stories to be included in that person’s newsletter, growing “smarter” with every reader interaction with the site.

“With that data, we build a list of articles that a reader did not read already, but the technology detects it as an interesting article for this reader,” Ownpage CEO and founder Stéphane Cambon told Nieman Lab. “Each newsletter is completely different for each reader.” Ownpage has seen publishers use its service in two primary ways: to grow their subscriber base or to provide an extra benefit to those who are already paying.

The French daily financial newspaper, Les Echos, for example, uses Ownpage to send its twice-weekly newsletter to all its registered users. The newsletter is the traffic source that’s generating the most subscriptions, and the conversion rate from overall newsletter recipients has increased by 10 per cent since Les Echos added the personalised email, according to Les Echos’ digital marketing and audience development director Yasmine Maslouhi.

“We really wanted to do something different to generate loyalty and to convert our newsletter users into subscribers,” said Yasmine Maslouhi, Les Echos’ digital marketing and audience development director.

8) Video

Video is hot. How many times have we heard that?

Big media companies have created video de- partments with dozens of video shooters and editors producing dozens of videos a week. But video is expensive and time-consuming. “Traditionally we’ve employed teams – someone out shooting and someone able to cut up and produce the video,” USA Today digital sports publications manager Chris Pirrone told the New York Times. “Doing that is, one, expensive, and, two, takes a while to turn around.”

What are the media companies that are not Hearst, Mondadori, Shueisha, India Today or Lagardère Media to do?

Enter two video production companies aiming to empower media companies to produce vastly more high-quality videos at reasonable costs.

Wibbitz, founded in October 2011 and based in New York City, is a text-to-video technology platform that automatically creates premium, short-form videos using text content.

Wibbitz’s customers include Bonnier magazines, Hearst, Gannett and the Weather Channel.

“For us, as a company with over 30 titles, it really allows us to create a lot more video,” Bonnier chief digital revenue officer Sean Holzman told The New York Times. Wochit, founded in May, 2012 and also NYC- based, is a video-creation platform enabling storytellers to create a branded, studio-quality video for any story in just 10 minutes. Customers of Wochit have included Time Inc., USA Today, CBS Interactive, The Huffington Post, Rotten Tomatoes, and NowThis News.

Both companies’ automation features operate similarly: Each analyses and summarises text, whether it is a story or a script, and then automatically searches for photos and video clips to go with the resulting video. Both use services like Getty Images and the Associated Press for video and images.

Both companies claim they can create a video for every published article on a site.

Both services offer animated captions on the videos, a feature Facebook has popularised with its auto-play feature causing many people to watch videos with the sound off, but with captions explaining either what’s being said or being seen.

And Wibbitz and Wochit also offer voiceover, either human or computer-generated.

Both companies share revenue with media com- panies, and Wochit sells subscriptions. Wochit claims to be producing 36,000 videos a month for its clients, a number that doubled in just six months from January to June 2016. Wibbitz claims to have doubled its client list in the same six months as well as increased its video production 600 per cent.

“The way we see it, we can help you increase your video inventory in a very significant way,” Wibbitz co-founder and CEO Zohar Dayan told The Times.

Editors can choose to be involved in the creation process, editing and adding material, or they can just let the automation roll along, comfortable after a while that the quality will be at least acceptable, if not better.

But experience has proven that readers can sniff out the automated videos. “The data came back very quickly that text-to-video alone, if you don’t touch it, consumers can quickly recognise it is not a high-quality product,” USA To- day’s Pirrone said.

Wibbitz CEO Dayan agreed, “There still needs to be a human, a process, to give that personal touch.”

At the end of the day, neither tool will be used to create videos on an industrial scale but to give editorial and ad staffs a powerful set of tools to supplement the work of video teams and freeing those teams up to do more sophisticated work, while also empowering non-specialist journalists to make videos as well.

9) VR Virtual Reality

If video is hot, virtual reality is scalding.

Big tech players – Google, Samsung, Face- book, HTC, Sony and Microsoft – are making big investments in the space.

And the stuff is pretty cool, right?

But pure virtual reality (VR) is also extremely expensive to produce, and the audience equipped to experience it is still extremely small.

However, there is a subset of virtual reality that is not so expensive to make and has the similar effect of putting you someplace outside of your reality.

It’s called 360 video. Consumers can enter that world for as little as US$1.99 for a pair of Google Cardboard “glasses” on eBay (US$15 if you buy from Google.). And publishers can play in that space for far, far less than the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars it costs to produce a pure VR video.

What’s the difference between virtual reality and 360 video?

Virtual reality is a general term for an immersive, out-of-the-present experience that can be controlled by the user to a greater (pure“synthetic” VR) or lesser (360 video) degree. Virtual reality (VR) puts users in an environment that gives them the feeling of being physi- cally present someplace they are not – either in places in the real world or in an imagined world – and allows the user to interact in that world.

In “synthetic” or imagined virtual reality (a world created by artists), the user can choose to go in a direction or take an action, and that dictates what happens next. By contrast, in a 360° video, users are surrounded by a real-world environment, but they go where the person directing the camera takes them. Viewers of the 360 video form of virtual reality are passengers, not conductors.

Let’s start with 360 video as it is the simpler and more accessible of the two virtual reality technologies.

“You need to be focusing on 360-degree video content right now, not VR – it is the most feasible option, both in terms of the overheads required in production of virtual reality, and how we can distribute it,” Associated Press interactive editor Nathan Griffiths told the World News Media Congress in Colombia in June 2016.

“It doesn’t make sense for me to spend a month building a VR piece that a handful of users might see on the Oculus or Samsung Gear, because I can make a [360] video that takes me a week to produce that gets seen by millions on Facebook and YouTube,” he said.

A 360 video offers, as its name implies, a 360-degree look at the world – up, down, left and right – with a swipe of the user’s fingers on a screen or just by turning their heads if they are watching on a headset like Google Cardboard.

And 360 video is still pretty damn cool. And popular.

In late 2015, the New York Times Magazine launched a virtual reality app called NYTVR which lets its users watch 360 video. To make it easier for readers to use the app initially, the Times distributed one million Google Cardboard VR viewers to subscribers. Today, the app has more than 850,000 downloads and over 10 million views and gets an average of 6.5 minutes of audience engagement per session, according to the Times.

“That’s 6.5 minutes of people putting cardboard up to their heads,” Andy Wright, senior VP/advertising and publisher of the NYT Magazine told Folio. “In digital media terms, that’s mind-blowing.”

About a year later in October 2016, the Times launched The Daily 360, offering readers a new 360-degree video experience every day.

The explosion of VR in the guise of 360 videos has been made possible by technology improvements impacting efficiency. For example, in 2015, editors had to manually stitch together video footage. By 2016, this process has become automated, reducing the time it takes to create each new video.

Plus, audiences seem to be catching on.

More than half of the NYT Daily 360 viewers are return visitors. “When you have 57 per cent coming back for more, month after month, that shows that they’re seeing this as a whole new way to experience and be present in a story,” Wright told Folio. “So we think this is something that will continue to build and be a big way in which The New York Times tells stories.”

Like readers, advertisers are drawn to 360 video. “They’re coming in all shapes and sizes and forms, often bringing ideas with them,” Wright told Folio. “On the commercial side of the business, we’re serving as a consultancy. We have more experience than any other publisher, and can guide marketers in terms of how to best tell their stories in this medium.”

Some publishers, like the NYT, produce the videos themselves. Others use outside VR producers. For example, 360 video content for Sports Illustrated was created in partnership with Wevr while InStyle magazine did 360 vid- eos with River Studios. And the Life magazine 360 video app, LIFE VR, will feature content created with California-based NextVR.

But magazine media companies needn’t go outside nor spend outrageous sums of money to create and edit 360 video. There are alternatives.

To review all the different camera and editing tool options would require more space than we have here (perhaps next year). But suffice to say that they’re easy to find and becoming less expensive by the day.

The good news is that journalists who’ve never thought of operating a 360 video setup, much less edit a 360 video, are now doing exactly that.

For example, the German news outlet Deutsche Welle, developed a 360 video editing system in collaboration with Berlin start-up Vragments, headed by Linda Rath-Wiggins, who is also a VR expert in Deutsche Welle’s innovation department.

Deutsche Welle and Vragments created a tool called Fader, which em- powers journalists with no virtual reality shooting or production skills to create and edit VR content.

“There is a lot of enthusiasm and excitement about VR journalism because it is a new way of storytelling,” she told the VR & AR World conference in London in late 2016.

“But there are lots of challenges associated with it, including time, skills, money and the uncertainty of what platforms we should be publishing it on, which Fader is designed to help with,” she said

Rath-Wiggins explained that when journalists use Fader to produce content, they shoot footage with a 360-degree camera, such as a Ricoh Theta S, then they import the files into the tool, edit the content there, and receive a url to share the final project with audiences watching on mobile devices, according to journalism.uk. “The idea has to be that one journalist in the newsroom goes out, shoots, and comes back and puts it all together,” she told journalism.uk.

Because the tools for watching 360 video are not widely adopted by consumers, most visitors watch 360 videos without a viewer on Facebook (which opened its Newsfeed to 360 videos in late 2016) and on YouTube’s mobile 360 channel, which still “is cool,” Niko Chauls, director of applied technology for the newspaper group Gannett told USA Today. “Add the viewer and it’s a mind-blowing, dazzling experience.”

The USA Today Network launched a week- ly virtual reality news show called “VRtually There” in the fall of 2016. Toyota was the inaugural sponsor with a 360° video that took viewers through Australia’s wilderness in a Camry.

The Financial Times also distributed Google Cardboard headsets to readers to enjoy a 360 video that took viewers through the favelas of Rio during the Olympics. It generated a quarter of a million views in just seven days. The FT also produced a branded content 360 video in 2016, a men’s style guide, showing casual and formal looks from the autumn/winter season, and made in partnership with Gieves & Hawkes, Armani, Orlebar Brown, and Turnbull & Asser.

In the spring of 2016, YouTube launched a dedicated 360° channel, and that autumn Facebook opened up the ability to view 360 videos in the News Feed.

Now publishers can post 360 content on two of the biggest video sites in the world, enabling users to navigate by tapping and dragging, or just turning their heads if they’re wearing a headset.

Virtual reality

“Next year will be the defining moment for virtual reality… as [media] organisations around the globe build dedicated teams to support the emerging platform,” USA Today Network design director of emerging technologies Ray Soto told the Nieman Lab.

“Expect a shift from experimental passive video to interactive experiences,” he said. “If your production teams haven’t already heard of these terms, get to know them: ambisonics, stereoscopic rendering, and photogrammetry will be standard by the end of the year.”

Well, maybe.

While consulting company Digi-Capital predicts virtual reality and augmented reality will become a US$120 billion market in revenue by 2020, many hurdles remain.

“One of the biggest challenges is awareness – when you walk into a coffee shop and ask people if they know VR, probably 20 per cent don’t have a good answer, let alone know how VR works,” Gannett VP and head of branded content Kelly Andresen told Digiday.

“We should definitely work as an industry to educate people on VR,” she said. “For example, publishers should at least introduce 360-degree videos to get their readers familiar with VR experiences that are totally different from traditional 2D films. Then they can introduce full VR experiences by developing a mobile app.”

“For brands and publishers that want to get into VR, cost and time is a big hurdle,” Andresen said. “It’s hard to find producers who have professional experiences in VR, and it costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to get started. I’ve never heard of a piece of VR content that cost less than $150,000.”

“The biggest challenge is having consumers adopt the VR hardware without the content being there first, while agencies and brands are afraid to produce the content until enough consumers have adopted the hardware,” digital marketing agency Isobar VP of innovation Dave Meeker told Digiday. “It’s a chicken-and-egg situation.”

Even if the awareness and content and hardware hurdles are cleared, there is still the question of context. When will consumers, other than gamers, use virtual reality headsets?

“So my question is this: Where does large scale VR usage fit into the media mix and where does it grow?” asked media consultant Bo Sacks in his blog.

“How much time in any given day will the public blind themselves to their surroundings and actually use VR? Will the public use it in the office, on the commute, or while waiting in line at the supermarket? Will large sectors of the adult population come home, kiss the wife and kids, and abandon them for the rest of the evening in the remoteness of never-never VR land?

“I’m not saying there isn’t a new media section of time spent with VR, I just don’t see it competing in any large way with social and live-in-the-moment, shared media experiences,” Sacks wrote. “VR has its place, but it will be much smaller than print, which is currently standing at four per cent of time spent with media.”

So keep an eye on developments, certainly try out some 360 videos, but don’t take out any big loans or go hiring a VR department full of techies. Yet.

10) Voice-Activated Personal Assistants

Remember Hal in the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey”?

It (he?) was a so-called sentient computer using artificial intelligence to control the systems of the Discovery One spacecraft and interact with the ship’s astronaut crew.

Well, now we can all have our own little Hals in our home and office and car and…

The arrival of “Hal” gadgets – voice-activated personal assistants like Amazon Echo’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, Google Home, and Microsoft’s Cortana – will much more dramatically change the content and consumer-relations game.

We are close to an era “when a screen for a device will be considered antiquated, and we won’t have to struggle with UX [user experience] design,” wrote Nico Bayerque, co-founder of Gone, an on-demand selling service. “Companies like Amazon and Google are already exploring this with the Amazon Echo and Google Home products; these are screen-less devices that connect to wifi and then carry out services.

“Thanks to IoT (Internet of Things), which is the implementation of an internet connection into devices beyond just our phone or computer – such as cars, TVs, stereos, and even washing machines – all these wi-fi devices have been entering our lives,” he wrote. “Looking toward the future, there will be less adjusting our ways of communication to fit technology and more of technology adapting to us – losing the graphical confines and learning our preferences, our cultural norms, and our slang, becoming more useful to us than we ever thought possible.”

Now, whenever our reader has an information need, we can deliver our content almost anywhere at any time whether our “reader” has access to a keyboard or not.

This is a massive opportunity to further cement our place in our readers’ lives, or an opportunity to massively lose ground to other more nimble, more need-focused content creators (think of your own advertisers who could eliminate you and deliver their messages directly to the consumer!).

As usual, the techies are seeing these gadgets as the next super big thing.

“So are these new personal assistants really as impressive as your technophile friends might suggest? Uh, yeah! They are. And they are positioning themselves to take control of your home!” wrote Mike Shames, director of San Diego Consumers’ Action Network, a non-profit consumer watchdog association. “Americans may find themselves talking more frequently to their voice-powered personal assistants offered by Amazon, Google and Apple than to their spouses, children or pets.”

Given what these gadgets do, that may not be an unrealistic prediction.

Amazon Echo offers 900 functions, enabling users to do everything from turn on the lights in their home, answer questions, order an Uber driver, take a quiz or find a recipe to play music, get a news briefing, play a game, do a therapy session, check their bank

account, order flowers, check movie times, make a phone call, check the level of petrol in their car, turn the heat up or down at home, order pizza delivery, listen to a book, stream music, do a yoga session, lock the doors at home, and much more.

While Google Home doesn’t yet have 900 functions, they are catching up rapidly and even offer some features Echo does not.

“It’s astonishing how quickly I’ve become habituated to asking Alexa for my flash briefing in the morning, and while I’m probably an early adopter, the commercial and convenience factor of devices like Amazon Echo will be enough to get them into a sizeable amount of homes – that’s another way that publishers can reach audiences,” wrote TheMediaBriefing.com news editor Chris Sutcliffe.

If magazine media aren’t aggressive in figuring out how to take advantage of these omnipresent devices, our advertisers might beat us to the punch and discover they don’t need us as much as they used to. If at all.

Readers are already getting there. Google says 20 per cent of all mobile searches are now voice searches. Mary Meeker’s KPCB 2016 Internet Trends Report showed that in May 2016, 25 per cent of searches on Windows 10 taskbar were voice searches. By 2020, a full 50 per cent, of all searches will be by voice, according to ComScore. Voice searches break down almost evenly into four categories – personal assistant (27 per cent), fun and entertainment (21 per cent), general information (30 per cent), and local information (22 per cent), according to research by Hound, a voice query app.

Here’s how a voice-activated personal assistant could work for a media brand:

“A publisher, say, Bon Appétit or Food and Wine, would create a ‘Recipe of the Day’ from a famous chef that could be loaded onto Alexa,” suggested Social Media HQ founder and CEO Chris Zilles. “Then, each morning, you could fire up your Amazon Echo and say, ‘Alexa, tell me the recipe of the day’. Alexa would read the recipe to you, and if you liked it, you could ask Alexa to put you in touch with the chef to get more details about the recipe. “However, here’s the big thing – you wouldn’t actually be talking to the chef, you’d be talking to an AI-powered bot of the chef,” wrote Zilles. “But this bot would know as much as Mario Batali or any other famous chef.

“That’s why Amazon Echo might start out being just a hardware device and turn out to be the next social media platform,” concluded Zilles. “Instead of typing in status updates with your fingers, you’d be sending them out with your voice. And instead of being friends with people, you’d be friends with bots. Welcome to the future!”

So there you have it: Enough new tech information to keep you busy for a year.

Our recommendation: At the very least, try out a 360 video, launch a chatbot, get an analytics tool that measures and analyses multiple metrics, and keep an eye on the rest.

We’ll be back next year with more…

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovations in Magazine Media 2017 World Report.