23 Oct Breaking news: the first 15 minutes of history

When a big story breaks, readers around the world instantly start paying attention to your reporting. Make the most of the opportunity

Wellington’s rider Major Henry Percy took three days, by horse, carriage and boat, to bring news of British victory over Napoleon along with two imperial eagles wrapped in French flags to London. None of the 56 newspapers published regularly at the time had sent any reporters to the battle and so could not tell their readers of updates from the field until the fourth day. 50 years later, when John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln, Associated Press correspondent Lawrence A. Gobright filed on the same day from Washington but failed to mention a bullet had entered the President’s body until the third paragraph, preferring to begin his chronicle with what amounts to a presidential diary entry.

By November 22, 1963, technology had improved. “In Dallas, Texas, three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade…” reported Walter Cronkite in an urgent CBS black-and-white television news bulletin, which did not contain any images at all given the rush to get the news out. He went back on air shortly afterwards to hold up a printed photo of Kennedy before he was shot: “This picture has just been transmitted by wire”. The image was stuck to a piece of cardboard. An hour after his first bulletin, Cronkite appeared live from his desk in the CBS newsroom with his now famous announcement: “From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official: President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time, two o’clock Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago”.

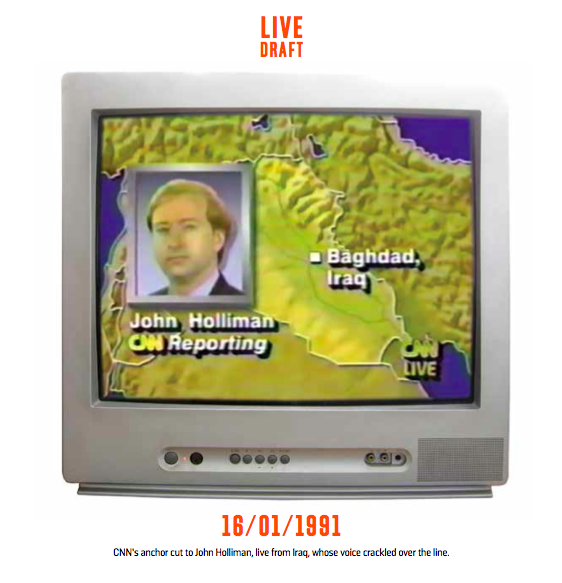

In 1991, a CNN team was in Baghdad with the newest gadget then available: a satellite connection. When the United States began its bombardment of the Iraqi capital, the cable news network broke in to a report by its Pentagon correspondent, Wolf Blitzer, who was attempting to confirm that the Gulf War had begun from Washington: “This war may be beginning right now”, said Blitzer: “the President may be going on television later on this evening”. CNNís anchor, David French, interrupted Blitzer and cut to John Holliman, live from Iraq, whose voice crackled over the line: “The skies of Baghdad have been just filled up with the sound of gunfire here tonight. There are still lights on all over Baghdad and there are bullets being fired up into the air”.

On November 13, 2015, viewers watching Germany play the French national team in a friendly in Paris and fans inside the stadium heard a muffled explosion from outside the ground as the players kicked the ball around. One of the fans inside, FT columnist Simon Kuper, posted on Twitter a minute later: “We have now heard what sound like 2 bomb explosions right by the Stade de France. Play continues merrily. Some unease here”. Ten minutes later, a second explosion was heard, and within 20 minutes gunmen had entered the Bataclan concert hall.

In each of the above examples, the first draft of history had just begun to be recorded. Days shortened to hours and then to minutes.

“If that happened again today it would be everyone connected to Twitter”, said Mark Little, in reference to CNN’s Gulf War broadcast: “we’d actually be getting it in first person”. Little was a journalist in 1991 and went on to create breaking news start-up Storyful in 2010. He is now Vice President of Media Partnerships in Europe at Twitter.

“I think every journalist has a lightbulb moment. For me, it was watching the protestors in Tehran (in 2009) telling their story firsthand. What happened was that passive became active, you could answer back”. Readers could communicate with participants in history for the first time, and in approximately real-time, with unexpected consequences. “The Arab Spring began with a hash tag, Mohammed Bouazizi was a food seller. It was essentially just a set of characters on Twitter but it became so powerful and something we could all join in on”, Little explained.

In 2016, both readers and people affected by the event on the ground want to know more about the story immediately, and traffic to search engines and news sites spikes. “Without question”, said Richard Gingras, Head of News & Social Products at Google: “Take the bombings in Brussels, when a story like that breaks, there’s a huge surge in interest, people are obviously looking for more information”. They want news about the event and they want contextual information about what to do next: “Probably the classic example is an earthquake in the Bay area, so you’ll immediately start seeing search queries like ‘was there an earthquake'”. In Brussels, people began searching for ‘trains out of Brussels’ or ‘get out of Brussels’. That global breaking news opportunity now lasts not three days, as at Waterloo, but about 15 minutes.

“The window has definitely gotten much smaller in recent years, especially on Twitter, I’d say maybe five to ten minutes if you’re lucky’, Storyful’s Head of News, Mandy Jenkins, explained. Reporters from global news outlets pile on to the first tweets from major stories anywhere in the world, bombarding eyewitnesses, victims and relatives with requests for photos, videos and quotes.

Alastair Reid, Managing Editor of First Draft,a British start up looking at all aspects of the new global breaking news environment, said journalists need a good ‘bullshit detector’ right from the word go: “A lot of places are really good at getting it right, and understanding that breaking news situations are uncertain, but what’s having an increasingly noticeable effect is the barrage of messages; it’s completely unmanageable, with dozens and dozens of journos from the world’s media descending on people”.

Fierce competition between outlets means it is unlikely any centralised solution will be implemented, despite the technology being available, and media organisations must also struggle with the ethics of the news environment: “If it’s an active shooter situation and that person thought they were safe but then had to hide, getting in touch with them might set o ff their phone”, Reid explained: “previously there was a police line: now journalists can digitally cross that line and contact an eyewitness who might still be in danger”.

After the first flash bulletin, or tweet, and as eyewitnesses on social media try to deal with the media onslaught, comes the first editorial dilemma: “Do we know enough to go with this?” wonders Jenkins: “Do we know enough to stand behind this? It’s a difficult decision to have to make every day. Speed is a high priority for us, being correct is more important”.

Julian Duplain, a Night Editor on the world desk of the BBC news website, faces the same challenge: “Yes, the main reason for that speed is Twitter, basically, which is an important conduit for us, all journalistic organisations are putting stuff on Twitter, we certainly do.”

“Someone sees a tweet and they would tell me or one of my colleagues, someone says there’s a fire in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and it could be interesting, so we’ve got to judge if it’s going to be big or not … so it comes straight to me; I might then ring up the people in Washington and see if it’s moving on US media”.

“Now, I think you’re losing credibility if you’re 15 minutes late”, he adds, highlighting how breaking news feeds directly into core issues of trust and even media brands’ business models. Outlets such as the Financial Times or the New York Times decide to take trust and correct reporting seriously and are also having some success with paywall models; other organisations – like The Daily Mail and Buzzfeed – prefer quick headlines to attract clicks and attention but sometimes get them wrong; those sites appear more focused on advertising.

In Madrid at the end of March, dozens of Twitter users across the Spanish capital suddenly began posting photos of everyone being evacuated from their tube stations. Had the next Islamic State terror attack begun? No.

Metro de Madrid quickly tweeted and informed those journalists who took the time to make a phone call that a computer glitch had set o ff the emergency alarm, ordering passengers and staff up into the fresh air above.

The same thing happened in London at King’s Cross station shortly after the Brussels attacks, said Reid: “a couple of places threw up a live blog, but then Transport For London tweeted about it just being a fire alarm. “In those kinds of situations, if it was something serious, there would have been all kinds of different information available, potentially thousands of people there who would have said something about it on social media.

The BBC has a six-person day team in London doing breaking news and social media, which shrinks to two on the night shift, and uses a tool called DataMinr to help gauge the impact of the latest topics people are tweeting about. The Wall Street Journal reported in May that Dataminr had “first notified clients about the Brussels attacks 10 minutes ahead of news media, and has provided alerts on ISIS attacks on the Libya oil sector, the Brazilian political crisis, and other sudden upheaval in the world”.

The BBC also uses a bespoke Content Management System (CMS) “which gives you the option to tweet, send an e-mail, push notifications and put an alert on a page”, said Duplain: “and that’s the important thing, one of the main reasons we have the tweets is to drive traffic to the story”.

Storyful has a team of 35 journalists around the globe, ‘hundreds’ of Twitter and Facebook lists, and is building a network of local experts and trusted sources around the world that it can turn to when a new story breaks. “We just generally have sources that we can go back to, nodes, connectors, people who can be helpful”, said Jenkins: “we have regular go-tos, local activists who we can call and find out more […] it is an extremely manual process to find out about people across different social networks”.

A New York Times magazine article about Obama’s strategic communications advisor Ben Rhodes caused a stir in May for its description of how he admitted to manipulating the media. “All these newspapers used to have foreign bureaus”, he told the magazine: “Now they don’t. They call us to explain to them what’s happening in Moscow and Cairo. Most of the outlets are reporting on world events from Washington. The average reporter we talk to is 27 years old, and their only reporting experience consists of being around political campaigns. That’s a sea

change. They literally know nothing.”

Some outlets are choosing not to to do breaking news. The Times of London, which has 500 journalists and production staff manning The Times and The Sunday Times newsrooms, announced in March that it was moving towards a more in-depth model in tune with its readers’ habits similar to The Economist, and would not be offering them the very latest updates instantly unless a really major global story like the Brussels attack broke. “We do have a ‘break glass’ scenario where we do break the publishing model”, explained Nick Petrie, The Times’ Deputy Head of Digital: “but that would be three or four times a year”. He said they would continue to do a push notification for something like the Paris attacks but that “you can’t really say much more than this has happened”.

Other companies believe plenty can be done in those 15 minutes to get readers the news they want. Context and verification are the hardest problems to solve. “The speed has gotten so much faster over the last 10 years”, said First Draft editor Reid: “There was a story at the end of last week, apparently with only witnesses, a boat capsized in the Mediterranean, no major news organisations have really touched it because there was nothing to go on apart from the people who were there. The only evidence is the testimony. Some places ran with it, and others didn’t because it just couldn’t be corroborated”.

“It’s so difficult to do verification because there are so many different versions”, agreed Storyful’s Jenkins: “language barriers, and the official sources on the ground are having trouble in that case (of the 500 drowned migrants). “We hit dead ends just like everybody else does”.

CNNís anchor cut to John Holliman, live from Iraq, whose voice crackled over the line.

Storyful founder and Twitter executive Mark Little is more optimistic: “Twitter is the best fact checking mechanism that has ever been invented. I can immediately contact sources that know what they’re talking about. For me, Twitter has given us the power to verify in real time in the world. Asked how social media might also amplify hatred and the evil side of human nature, as radio broadcasts fuelled the genocide in Rwanda in the 1990s, he answered that: “Radio could broadcast propaganda and no one could check it. Twitter has made me a better journalist”.

Google’s Gingras admits the algorithms are good at finding the latest stories based on volume and clustering them in Google News but that they struggle to find what might be the ‘best’ story for readers: “Obviously this is all computer driven, it’s comparatively easy to tell which is the fresher story, there might be a story which is less fresh but more nuanced, there are so many factors that come into play, you’re getting into the most tricky nuances”.

“That is precisely what The Times is intending to concentrate on, only in daily blocks at 9 a.m., 12 midday and 5 p.m. as opposed to right now. Its readers could not live without ‘analysis, context and commentary’, said Petrie.

That is what they say they want to pay for.

“There’s definitely a market for hot takes”, said Robert Colvile, a former Telegraph leader writer and comment editor and the author of !e Great Acceleration: “When I was at The Telegraph, on budget day we would flood the pieces with comments, the things which did best was always someone who really knew their stuff, who takes three or four hours and comes up with a new angle”.

Colvile said forget about the 24-hour news cycle: “if 9/11 happened now, people would be putting up footage of the first tower from the second tower, the horror we all felt would be much more immediate”.

He also highlighted how modern history’s participants know full well that technology has increased the speed at which media cycles work and attempt to use it to further their own goals. Trump is a master, Colvile said: “he’s rewriting the entire industry of political campaigning; if you’ve got a colourful enough personality, you can command the media agenda”. Trump knows it too. He told Fox News’ Morning Joe TV show that he has more than 7.5 million followers on Twitter, seven million on Facebook and two million on Instagram: “that’s like owning the New York Times without the losses. Why should I give it up?”.

Twitter has owned the first 15 minutes of history for the past six or seven years, thanks to its immediacy and network of users, but other companies are now moving aggressively into the space, and technology invented to solve other problems has the potential to disrupt the status quo. Google recently launched its Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP) project and Facebook opened its Instant Articles platform to all publishers. Both were designed in response to over-heavy pages loading too slowly on smartphones as mobile use rockets around the world. Facebook is fighting Google for the planet’s attention and its Instant Articles allow newsrooms to hook up their CMS to publish directly and immediately to the news feed.

Crucially, newsrooms can update those articles on Facebook at the same time as they update their home page or live blog. Smaller companies such as Pusher and Ably are working on live connection and push notification networks that promise service in the hundreds of milliseconds range, a feature only previously available to high-frequency trading companies close to stock markets.

Facebook has also announced a live video platform to rival Twitter’s Periscope and has a tool called Signal, currently available mostly to journalists in the United States, that helps reporters search the millions of updates posted by users. “We’ve seen a number of cases where breaking news is a big part of what news organisations are doing on Facebook”, said the company’s Director of Global Media Partnerships, Andy Mitchell, citing a major fire in New York in April as a good example of how a well-known TV anchor went live from the scene via Facebook Live. At the beginning of May, a Washington Post reporter in Pyongyang broadcast to Facebook from her cell phone, without her North Korean handlers being aware of what she was doing. “Facebook is about news that people care about, so if that is breaking news”, said Mitchell: “Facebook is not creating content […] if publishers want to send people to their own domain or properties, that is their choice”.

How live, instant updates to Facebook’s gigantic worldwide audience and millisecond mobile connection uptime guarantees will affect the way breaking news is done is anybody’s guess right now. Perhaps the 15-minute window will shrink to five minutes. The implications for the first draft of history, and history itself, are also open to interpretation. “Ted Sorensen, Kennedy’s media guy”, said Great Accelerator author Colvile: “said that if the Cuban missile crisis had happened now, we’d have launched the first strike, because of the media pressure, the general pace”.

INNOVATION’S TAKE: Breaking stories are the leading edge of news, the start of major stories that can change history. It is a fast, intense space to work in nowadays. With the right technology, tools, phones, team and network of sources, though, there is no excuse for your media organisation not to compete on behalf of you readers, for global stories, local latest updates or news related to your particular niche. Have a senior journalist or editor in charge of the breaking news desk and give that person control of your outlet’s Twitter feed. Report relentlessly and get quick out to your readers, on whichever platform they want their alerts on.

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovations in News Media 2016 World Report.