30 Jan FEWER SHINY THINGS, PLEASE!

Enough already! Media companies are starting to use tech not just because they can, but because the tech they choose adds value for the reader or advertiser

Remember when we (or at least some of us) thought people really would wear those monstrous, ugly headsets to enjoy the (few and expensively produced) virtual reality experiences we created for them? Or when we thought that the tablet was THE answer to all that ailed us? Or that 360-degree video was worth the expense and that advertisers would love it? Or that we’d soon be sending stories to readers wearing Google Glasses?

That was (and still is) the so-called “Shiny Things Syndrome”. Some of us have spent and continue to spend a lot of time and money on those things.

Well, someone finally called us out on it. In late 2018, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism issued a report entitled “Time to step away from the bright, shiny things? Towards a sustainable model of journalism innovation in an era of perpetual change”.

“The Shiny Things Syndrome takes away from storytelling and we risk forgetting who we are; that’s the biggest challenge,” Kim Bui, Director of Breaking News Audience and Innovation at the Arizona Republic in the US, told the Reuters Institute.

“There is evidence of significant change fatigue and burnout that risks impacting on journalism innovation efforts, in part caused by relentless pursuit of ‘bright, shiny things’,” wrote report author Julie Posetti.

“To be clear, my report does not amount to a call to stop innovating, nor justification for doing so, but it is a plea to avoid unsustainable approaches to innovation that fail to take account of potentially negative impacts — approaches that risk wasting time, effort, and money, without real returns,” wrote Posetti.

So what tech tools are not shiny new things and actually work?

Some media companies are turning formerly shiny new things into real, useful, successful media tech, such as voice-enabled devices, Artificial Intelligence (especially for robotic content creation), and Messaging Apps, among others.

The former shiny new things with the biggest immediate potential are those voice-enabled devices that are gaining traction in a big way. Some media companies are already having success with them.

Voice interfaces are being adopted faster than nearly any other technology in history. Today, over 47 million Americans in more than a quarter of US households have access to smart speakers like the Amazon Alexa and Google Home, according to the 2018 Voicebot Smart Speaker Adoption Report. That number represents a stunning 128% increase from 2017, when the devices first spiked in popularity, according to TechReport.

The penetration of US broadband households with smart speakers will reach nearly 50% by 2022, according to a new study by consumer tech market research company Parks Associates.

But the meteoric rise of the smart speaker doesn’t stop there: The steep growth trajectory of smart speakers is matched only by the smartphone, according to AppDynamics, an application performance monitoring company.

The global number of installed smart speakers is going to more than double to 225 million units by 2020, according to global tech analysis company Canalys. Voice shopping on Alexa alone could generate more than US$5 billion per year in revenue by 2020, according to RBC Capital Markets.

Digging further into voice-based activities, 30% of web browsing sessions will be voice-based by 2020, according to Gartner, a global research and consulting company.

For example, a PwC survey in late 2018 found that more than one-third of Americans already use voice searches every day and half use them monthly to check on news and weather. Even more importantly, almost three-quarters of survey respondents said they would prefer using their voice-enabled device to search for something online rather than having to type their query!

So, who’s finding voice-enabled success?

In late 2017, National Public Radio (NPR) in the US could only claim that a measly 4% of their live streaming listening hours came 1 through smart speakers. One year later, that number had skyrocketed by almost 500% to 19% of live streaming hours, according to Tamar Charney, Managing Director for Personalisation and Curation at NPR, speaking to Recode.

That’s pretty cool, but what’s really cool is that the gain has not come at the cost of listeners to any of NPR’s other live streaming platforms, according to NPR.

Podcasts, too, are seeing a growth from smart speaker owners. Listeners spend twice as long listening to podcasts on smart speakers than they do on their phones, Cara Meverden, founder of voice-controlled podcast curation app Scout FM, told Recode.

The growth in smart speaker adoption is being driven by big improvements in the tech behind the services like Google Home, Alexa and Siri. For example, Google’s machine-learning-backed voice recognition system has achieved 95% word accuracy for English. That number happens to be the threshold for human accuracy, making Google’s tech just about as accurate as human understanding.

The news gets even better when you look at stats around smart speakers and advertising. Smart-speaker listeners are less prone to skip through ads than those who listen on computers or phones, according to Meverden: “People are much less likely to skip ads on Alexa. It’s more inconvenient to tell your Alexa to skip forward 30 seconds than it is to just let the ads play,” Meverden told Recode.

“Smart speaker listeners are much more passive. People with voice interfaces tend to accept what’s given to them.”

What all the growth statistics tell us

“I think people are realising how much consumer time and attention is going to be spent on voice devices, and what that means from a marketing standpoint is that they’ve been essentially invisible so far,” Corbin de Rubertis, the head of the new Meredith Innovation Group, explained to Folio. “Neither Apple nor Google have made any attempt to really give advertisers a place to play, so we’re really taking it upon ourselves to make it happen.”

At Meredith, de Rubertis has tested some of their food brands on voice-enabled devices. For example, on their AllRecipes site, a call-out is embedded in an article, in both print and digital, inviting the reader to “ask Alexa to open the AllRecipes skill,” which then enables the reader to get even more information about the recipe and even order ingredients for that recipe.

While monetising podcasts and other content-to-audio options is difficult, for smart speakers the skills and actions allow advertisers to get consumers to fill their shopping carts directly, according to de Rubertis.

“The skills are actually the best place to do the product placement and direct links to commerce, whereas the strictly audio experiences follow the old radio paradigm of ‘brought to you by’,” he said.

So if a Better Homes & Gardens skill sponsor wants a specific cleaning product placed in the content, the reader can be prompted to ask Amazon’s Alexa to add that product to their shopping cart right then and there, he said.

At the BBC, their magazine media brands (which are owned by BBC Worldwide and published by Immediate Media) such as BBC Good Food are using voice platforms extensively.

“We’re always working hard to ensure our content remains as relevant and useful as possible for our 20 million monthly users,” Hannah Williams, BBC Good Food Editor, told FIPP. “Being able to enjoy our recipes hands-free is of enormous benefit to our audience, especially when grappling with a particularly messy recipe. As the user benefit was clear, it felt the right place to be as a business.”

The magazine, which has a cross-brand reach of 13.9 million and is the UK’s most popular food media brand, launched its first Alexa custom skill in the fall of 2018.

“Users can search our entire 11,000+ recipe database, filter by preferences such as diet type or cuisine, hear the full ingredients list and stepby-step method, pausing to set their own pace, all completely hands-free,” Williams said.

Hearst started with horoscopes

Hearst launched their first skill in 2015: Elle magazine’s horoscopes. “(Horoscopes) felt like a natural, straightforward experience to bring to voice platforms,” Chris Papaleo, Hearst Executive Director of Emerging Technology, told FIPP.

“We’ve seen really great traffic on that and it has been a really sticky experience, because it lends itself to a daily habit and is not too complex to navigate.”

Hearst also launched voice content on Alexa from Oprah magazine last year, called Oprah Magazine, which shares the media maven’s words of wisdom each day, in her own voice. Hearst launched a Good Housekeeping Alexa skill that is designed to help people get stains out.

“If you spill wine on your couch you can ask Alexa or ask Good Housekeeping what materials you need to clean it and what the steps to cleaning it are,” Papaleo said. “In a hands-free context, that might be a really useful thing to surface to users, from stain experts at Good Housekeeping,” he said.

“That’s the challenge — making sure each voice interaction is a useful one,” he said.

To test monetisation, Hearst launched My Beauty Chat on Alexa, a twice-daily podcast that features editors from Good Housekeeping, Cosmo, Oprah and Elle, that has been sponsored by L’Oréal.

My Beauty Chat’s sponsorship by L’Oréal was the first sponsorship model Hearst has been able to explore. Papaleo said monetisation is a challenge, but they’re looking at other ways to monetise their voice content. “That’s been the challenge — can you really make money on these? — but we’re trying to carve a path and Amazon and L’Oréal deserve a lot of credit for opening it up for us.”

One of the other challenges with voice platforms is how to measure them. Because the technology is so new, metrics are undefined. Amazon uses the phrase “utterances” to define anything a user says while using skills, but as an early adopter, it’s up to Papaleo and Hearst to figure out what the new “click” is in the voice environment.

“Right now, we’re looking at number of users, how many sessions those users have started, the sessions-to-user ratios, and the utterances-to-users ratios as indicators of healthy experiences and an engaged listener.”

Should publishers develop for Alexa or Google Home?

At the end of 2018, eMarketer forecast that Amazon Echo will drop below two-thirds of US smart speaker users for the first time in 2019. Amazon Echo will capture 63% of smart speaker users in 2019, while Google Home will account for 31%, according to US-based market research company eMarketer. Smaller players, such as Sonos One and Apple HomePod, will take 12%.

Amazon’s share will shrink through 2020, while those of its rivals will grow, eMarketer projected. The company pointed out that there is overlap among the brands, as some people use more than one device.

So, which platform do you focus on? You can roll the dice and pick one of the dominant products and build a solution for it. Or you can target them both.

If you focus on one platform, you can stay focused from a development perspective and spend less, but you cut back audience reach. If you develop for both platforms, you get the best reach but that course is more expensive and takes longer because your team’s attention is split.

It is clear, however, what you cannot do: Ignore voice tech.

“Wherever you stand on the audience penetration forecasts for voice, it’s clear it will become a disrupting force for publishers in future, so ignoring it is not an option,” BBC Good Food Editor Williams told FIPP.

There are all sorts of pending applications for artificial intelligence (AI), but the one making the most waves right now, and actually delivering results, is content creation by AI robots.

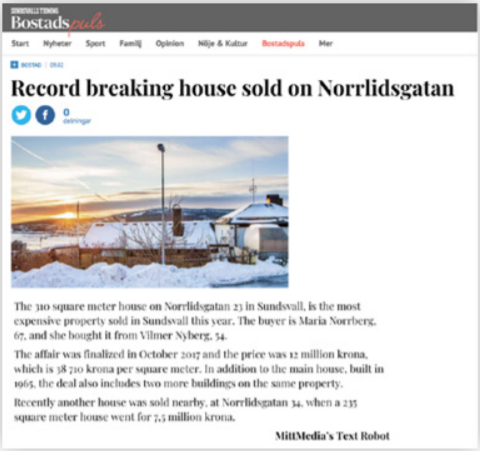

MittMedia, one of Sweden’s largest media groups with daily newspapers, printers and commercial radio stations, has figured out a way to use AI robot-generated content to actually drive subscriptions.

While the focus on “robo-journalism” has tended to be on time savings in busy editorial departments, MittMedia found out that using robots to generate real estate articles has resulted in adding 1,000 new subscribers in a single year to its total of 80,000 digital subscribers across 20 of its local news sites. Subscriptions cost roughly US$11.50 a month.

At the end of 2017, MittMedia launched an AI-powered bot called the “Homeowners Bot” that, using home sales data, writes short articles on every house that is sold in a local market. The bot is programmed to grab an image of the home from Google Street View and search each sales listing and local market sales data to find the most interesting angles, such as the most expensive house sold in a market in a certain time period.

The bot now cranks out almost 500 stories a week on home sales, constantly adding to an archive that numbered 34,000 in February 2019.

“A really good robot text can have a bigger impact and be more read than a really good news article, but only if it’s a topic readers really care about,” Li L’Estrade, head of content development at MittMedia, told Digiday. “Each article reaches a smaller group of readers on average, but in total, we get an exchange on par with anything written by our most-read reporters.”

Every bot-written article carries an unusual byline: “By MittMedia’s Text Robot”! According to the company, more than two-thirds of respondents to a survey said they didn’t suspect or notice the story was written by a robot.

Other media companies have used AI-powered robots to generate stories using structured data. This approach is particularly useful for media companies such as Bloomberg, Reuters, and The Washington Post, where they have data-rich topics that are frequent story subjects, such as sports and business. Using structured data and robots, those media companies have been able to crank out a high volume of simple stories, freeing their professional staff to do the more creative and often investigative work. The high volume of robot stories also helps increase ad impressions.

Caveat emptor

But here is one caveat: In February 2019, OpenAI, a non-profit research company backed by Elon Musk, created a new AI text-generation model called GPT2 that they decided was so good and the risk of malicious use so high that OpenAI refused to release it to the public as they have with every other tool they’ve developed.

The way GPT2 works is that its AI system is fed a partial-text story and then, based on the program’s analysis of that text, it writes the sentences that it “thinks” should follow that text.

For example, when fed the opening of a story about Brexit in The Guardian, GPT2 spit out a perfectly plausible story, including “quotes” from Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn and a prime minister’s spokesman’s retort “quotes” to Corbyn’s “quotes”.

OpenAI, to demonstrate the potentially pernicious power of GPT2, created versions of the tool that could generate infinite positive or negative reviews of products. Similarly, GPT2 can be set up to create bigoted stories, conspiracy theories, and more.

So, while AI-powered robot “writers” have great potential to help media companies drive revenue and subscribers, the potential to do damage also exists and must be guarded against.

We’ve been told for years that messaging apps are the future for media companies looking to reach readers, especially as social media giants stumble.

The latest messaging app usage statistics show that the global powerhouses WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger have 1.5 billion users worldwide, and WeChat and Viber are just behind — both at roughly the 1 billion mark, according to messaging services company MessengerPeople.

Below the top three, we have: Viber (1b, popular in countries like Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina); LINE (203m users, especially popular in Japan and Taiwan); and Telegram (200m, popular in Iran, Uzbekistan, and Ethiopia), according to Inc.com. Beyond those, there are many others, including Tango (390m).

“Nine in 10 internet users globally have used some kind of chat or messaging service within the past month,” according to Erik Winther, Insights Content Manager at GlobalWebIndex.

“Clearly, messaging apps are where social media is going next, and we and other publishers need to figure them out,” Tom Standage, Deputy Editor at The Economist, told WhatsNewInPublishing (WNIP).

“Facebook’s well-publicised problems have led to a substantial decline in use for news with other networks picking up the slack,” according to a September 2018 report from the Reuters Institute for Politics. “Many apps are benefiting from this state of affairs. As messaging apps such as Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp grow in popularity, they are increasingly being used to share and discuss news, away from the toxicity of political debate that threatens more open spaces.”

The messaging app ecosystem offers distinct advantages for media companies looking to reach readers. The apps offer massive, as-yet untapped audiences as well as unusually high engagement through push notifications and unique tools such as chatbots and stickers. In addition, messaging apps give media companies the opportunity to build community using chat rooms and crowd-sourced storytelling.

Where to start?

“There are so many messaging apps, it feels like you should be on all of them” Carla Zanoni, Wall Street Journal Editor/Audience & Analytics, told WNIP. “Have a deep understanding of who your audience is and what their needs are. Make sure you’re in the space where your audience is already active. Spend some time listening to your audience, to hear what it is they need. You want to provide some utility and service on those apps.”

Some media companies are already there. The BBC, WSJ, Huffington Post, and The Washington Post have been in the messaging app space for several years.

In late December 2018, The Washington Post announced it was furthering its experimentation on Viber by introducing a chatbot and a second collection of journalism-themed stickers.

The Post’s global news bot is the first to appear on Viber and will be available to all users. The Post’s chatbot automatically sends users the top headlines from five different news sections — Politics, National, World, Opinions, and Entertainment — directly within the app. Users can opt to receive news updates either daily or weekly. They can also receive additional updates from their sections of interest by simply tapping on that section’s icon. The feature includes a dashboard with options for users to subscribe to The Post, watch original video content, and invite friends to sign up for the chatbot.

The Post chose Viber because, while it is less popular than WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, it is showing steady growth and thus is a key player, especially in Eastern Europe.

Another reason is that Viber offers media companies distinct advantages over WhatsApp, which sets a limit of 256 subscribers for each channel. Every time a media company hits that number, they have to create a new channel to be able to acquire new subscribers. On Viber, an unlimited number of users can sign up for a channel.

The upshot? If it takes three minutes to publish something on Viber, the same process could take up to 30 minutes or more of duplicative work on WhatsApp, depending on how many channels you’ve had to set up.

Monetisation

But the same problem faced by AR initiatives plagues messaging apps: Monetisation.

The advertising landscape for messaging apps will be more challenging than it has been for social media,” said GlobalWebIndex’s Winther. “Apart from WeChat, which has a regular feed, many messaging apps lack a central place where display ads or sponsored posts can be run.

“Already, far more people have interacted with a brand on a messaging app than have followed a brand, viewed a Snapchat show, or even swiped up on any brand’s stories,” said Winther. “WeChat is the only channel where branded accounts have a strong uptake. For the rest, it seems content isn’t king — yet — and perhaps until the messaging apps and services rethink the consumer needs as well as usage.”

In the end, we now know that media tech can be a tempting (and dangerous and expensive) trap that is best tested against one criterion: Does a tech tool advance our ability to meet the needs of our readers and advertisers? Being cool is not necessarily the same as being profitable.

The dust is finally starting to settle around the kerfuffle created by Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR).

What’s left standing appears to be AR, with VR relegated for now to a hobby for rich folks.

Media companies seem to be betting on AR, and that bet is bolstered by some significant AR work created by several AR projects created in 2018 by The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Time Magazine.

AR, in comparison to VR, benefits from the fact that it is much, much less expensive to produce. A single person can whip up a simple augmented reality experience in just a few weeks, according to Dan Pacheco, Chair of Innovation at the Newhouse School of Syracuse University, speaking to Digiday. For example, The New York Times’ AR team managed to produce an augmented reality component for a story about Syria in less than a week, he said.

Nonetheless, AR still faces challenges from tech to monetisation.

In terms of tech, while consumers now have the ability to view an AR piece using almost any new smartphone, distribution is complicated by an app system that is terribly fractured and diverse.

But when Apple and Android empowered developers to add AR features to mobile apps in 2017, that moved AR to a level of mainstream adoption.

“That solved the audience problem in an instant,” Graham Roberts, Director of Immersive Platforms Storytelling at The New York Times (which produced 13 different augmented reality projects in 2018 alone) told Digiday.

The answers to the monetisation problem are more difficult. Advertisers have long been aware of AR, but they seem to believe it is great for apps but not for ad insertion.

“This is engage, not sell,” Justin Archer, Senior Vice President of Innovation at the media agency Moxie, told Digiday. “They can’t take their traditional types of ads and apply them to this medium, so they’re having to work a little harder.”

That said, eMarketer projected in a late 2018 report that “AR advertising will grow quickly over the next several years. It is currently dominated by social media companies — including Snapchat and Facebook — which are aggressively building out their offerings and measurement models. New self-serve options, which are relatively easy to experiment with, are easing AR adoption among both brands and consumers.

“Brands that want to make their AR experiences ‘stick’ long term will eventually need to pivot from novelty to utility,” the report said. “Winners will use AR to meet their audiences’ specific needs for information, convenience and entertainment.