16 Oct FREE MONEY? NOT EXACTLY: Philanthropy funding is neither free nor easy nor widely available

The idea on its face is intoxicating: Large foundations or donors give you money to do what you want to do anyway. No advertiser hassles. No campaign deliverables. No subscriber cancellations.

All you need to do is find simpatico foundations and cash their checks, right?

If only it were that easy.

Philanthropic funding of journalism is happening, but it’s barely a drop in the bucket and what little is happening is heavily concentrated in the United States with a sprinkling in Europe and virtually nothing happening anywhere else in the world.

More than 93% of journalism-focused grant money goes to US-based organisations, leaving just 6% for Europe, and only about 1% for media outlets in the developing world, according to Media Impact Funders (MIF) and the Foundation Centre.

When you take a deeper dive to see where the philanthropic support of journalism goes, it quickly becomes clear that the lion’s share of the money is not going to publications but elsewhere.

Where is the money going?

More than two-thirds of philanthropic funding of journalism goes towards what could be described as services: university programmes, professional development groups, and research and technology development, according to MIF and the Foundation Centre. Another fifth is awarded to the thematic cluster of press freedom, open access and technological innovation in media, according to the Centre.

“There is not enough philanthropy from the rich — or charity from the rest of us,” wrote media critic and City University of New York professor Jeff Jarvis on his “Whither News” blog on Medium in early 2019.

“A Reuters Institute survey found that a third of executives expected more largesse from foundations this year,” Jarvis wrote. “Well, last year, Harvard and Northeastern [University] published a study of foundation support of journalism, totalling up US$1.8 billion in grants over six years. Not counting support for education (but thanking those who give it), I calculate that comes to less than US$200 million a year. For the sake of comparison, The New York Times’ costs add up to almost US$1.5 billion. The grants are a drop in the empty bucket.

“Foundations can be wonderful but they cannot support all the efforts that think they are worthy,” Jarvis wrote. “They also tend to have ADD [Attention Deficit Disorder], wanting to support the next new thing. They are not our salvation.”

How much do magazines get?

When you break the numbers down to focus only on magazine journalism philanthropy funding, the picture gets, well, downright discouraging.

After analysing more than 30,000 grants (totalling US$1.8b) from more than 6,500 foundations between 2010 and 2015, Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy and Northeastern University found that foundations supported legacy magazines to the tune of just US$80.7m over that five-year study period.

By comparison, over that same time period, foundations sent four times that amount (US$331m) to mostly newer, digital-based non-profit news-oriented organisations, including national non-profit news organisations (US$216m), local non-profit news organisations (US$80.1m), and university-based journalism initiatives (US$36m).

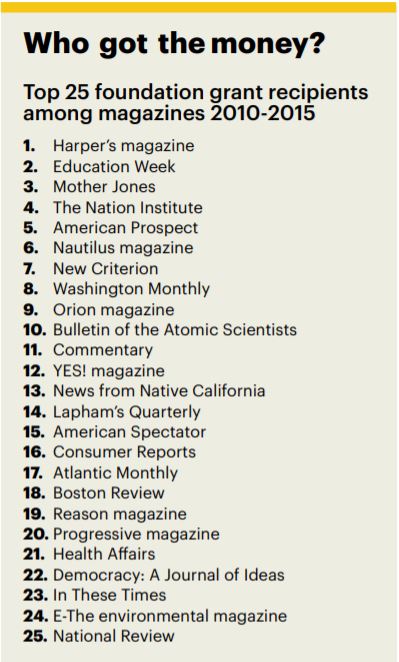

Just 25 magazine media organisations received 99% of all magazine philanthropic funding, according to the Harvard study.

More than half of those recipients were political magazines: Nine were liberal or left-wing media companies and five were conservative or right-wing magazines. The remainder broke down by topic as follows: three public affairs magazines, two science/ technology, two environmental/conservation, two minority/ethnic issues, two general public affairs, one focused education, and one consumer affairs.

Of the US$80.7 million total, Harper’s received more than a quarter ($23.7m) of the total. The liberal magazines got nearly as much (US$22.8m), the conservative magazines got a (by comparison) paltry US$6.5m. Education-related magazines receive US$14.5m, science/tech magazines received US$5.2m, and environmental magazines got US$2.6m.

After Harper’s, Education Week was the next biggest winner at US$14.5m, followed by political magazine Mother Jones at US$6.6m, the National Institute at US$5.6m, and American Prospect at US$4.2m.

There are success stories

Despite what could look like a daunting business model challenge, there are significant philanthropy-based media company success stories out there. Philanthropic donations have helped sustain national and local news outlets like ProPublica, the Center for Investigative Reporting, the Voice of San Diego, Texas Tribune, and others.

The concentration of philanthropic support of media companies in the US is not necessarily the result of Americans being more generous.

The difference is the charitable tax deduction that US donors get, which provides a strong economic incentive for giving and has helped support non-profit news outlets across the country, according to Global Investigative Journalism Network Executive Director David Kaplan speaking to the Nieman Lab.

Foundation donations to journalism have continued to grow.

In Germany, the Brost Foundation made a substantial investment in Correctiv, a German version of the US-based ProPublica, and the Schöpflin Foundation pledged almost US$30 million to the creation of a future House of Non-Profit Journalism, according to European Journalism Centre grant consultant Eric Karstens writing on global philanthropy magazine alliance.org.

And in Asia, public interest non-profit newsrooms such as the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, South Korea’s Newstapa, Taiwan’s The Reporter, and IndiaSpend are proving, in various ways, that there is local support in Asia — through grants, donations, memberships, and sponsorships — for independent media, according to Kaplan.

Story- or series-specific funding

Another avenue of philanthropic support of media comes from the sponsorship of stories or series.

In the United States, for example, foundations donating to public media organisations between 2010 and 2015 dedicated almost US$100m for either specific subject coverage (US$80m) or local/state coverage (US$20m), according to the Harvard study.

Even if you get the money, all is not roses

There are downsides to this “free” money.

“The overriding concern about philanthro-journalism has been that foundations may compromise journalists’ autonomy,” wrote Martin Scott, Senior Lecturer in Media & Development at the University of East Anglia in the UK. “New York University Professor Rodney Benson, for example, has warned that media organisations dependent on foundation project-based funding “risk being captured by foundation agendas and [are] less able to investigate the issues they deem most important.”

“Unfortunately, one of the other unintended consequences of this often-protracted process is that news outlets can spend a great deal of time and resources cultivating open-ended relationships with a range of foundation representatives and generally enhancing their ‘visibility’ and ‘presence,’” wrote Scott on the Nieman Lab blog. “This matters because it can take resources away from their editorial work, leading to a reduction in news output.

“This informal process of securing foundation funding also favours larger news outlets, such as The Guardian, which have the capacity to absorb the relevant marketing tasks,” wrote Scott. “As one interviewee put it, ‘it’s the same groups that tend to get the funding… I understand, practically, why they do that, but it does make it very difficult to break into that world.’”

Clearly, the philanthropy-based business model is not a model for many media companies. Not even for the vast majority.

But for those companies whose mission matches the interests of enough well-heeled foundations, and who have the infrastructure to write and compete for grants, there are successful precedents. Just don’t go mortgaging the house waiting for those grants…