29 Aug What´s Next: The Evolution of Audio

The Innovation in Media World Report provides a comprehensive snapshot of the key technological paradigms that publishers need to navigate in order to keep their businesses relevant and thriving in the years ahead.

THE PODCAST ADVERTISING BOOM The initial fear with Covid-19 and lockdowns around the world was that they would change audio listening patterns drastically, dealing a serious blow to the burgeoning podcast industry. We now have several indicators to suggest this is not how things played out, and two years on from the start of the pandemic, the business and revenue potential of podcasting for publishers looks healthier than at any time.

Firstly, though commuting time, often considered key to podcast listening habits, went down all over the world, the 2021 Digital News Report from The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism notes that it did not really move the needle on consumption. With many publishers racing to create new products to explain different facets of the pandemic and how it had changed life around us, podcasts and newsletters were key, and the report notes that “podcasts have become a key part of many lockdown routines with more consumption at home.”

Second, as Oregon University professor Damian Radcliffe says, it is worth noting that in the U.S, research has historically suggested that the bulk of podcast listening — even pre-Covid — was done at home. What we can conclude then, is that while there was a loss in terms of commute time, the overall numbers for podcast reach remained fairly neutral. On the other hand, what did grow fairly dramatically, was advertising for podcasting. A study of U.S. podcast advertising done for the Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB) showed revenue of $842 million in 2020, a nearly 20% increase over the previous year. At that rate, podcasting revenue was predicted to exceed $1 billion in 2021. Writing for The Fix in March 2022, James Breiner gave significant indicators as to why advertisers were increasingly choosing podcasting as an option – in particular, a new advertising technology called “dynamic insertion“. It allows advertisers more flexibility to quickly switch out messages as needed at the point where the listener downloads the podcast. Dynamically inserted ads increased their share of podcast revenue from 48% to 67% year over year.

In March this year, a new study commissioned by The Guardian found that podcast advertising raises positive perceptions of brands and encourages listeners to take buying action. The nationwide U.K. study, conducted by independent research company Tapestry, looked at the effectiveness of podcast advertising and found that it commands the highest levels of attention of any media channel. The study found 65% of listeners paid attention to podcast adverts – more than adverts on TV at 39% and adverts on the radio at 38%.

These high levels of attention, the study found, translate into greater likelihood to buy the product or service being advertised. For example, 51% of weekly users of each channel said podcast adverts made them want to buy something from the brand versus 38% for radio. Speaking to Digital Content Next, Radcliffe also points out that the podcast audience is typically more affluent, more educated and has a higher disposable income, making it a very attractive segment for advertisers. “The other big factor here is that podcast advertising tends to be pretty limited & there’s a value in that exclusivity for podcasters which is quite appealing,” he adds.

These are trends confirmed by other research — The Super Listeners 2020 study from Edison Research, for instance, found that 48% of respondents reported paying greater attention to podcast ads than any other form of media advertising. A big reason for this was due to presenter reads.

In his piece for The Fix, Breiner points to the example of National Public Radio (NPR) in the U.S. to illustrate the dynamic between a drop-off in listenership but a corresponding rise in ad revenue. NPR lost a fourth of its audience for live shows over 2020. By the end of that year however, it was on track to make more money advertising on podcasts than on its conventional radio shows. NPR now has four of the top podcasts as measured by weekly listeners, according to Edison Research.

Other companies with a heavy focus on podcasting also saw the money coming in after years of investment. The online magazine Slate, for instance, which has a roster of news analysis shows combined with longer form interview and narrative podcasts, reported in 2021 that half of its ad revenue was coming from podcast advertising.

THE PODCAST SUBSCRIPTION WARS HAVE ARRIVED For some time then, advertising will continue to be the main revenue stream for podcasts, potentially as one of the biggest winners from the global bounceback in digital ad spending. There’s a movement building up in parallel though, and it’s the rapidly evolving landscape of successful paid-for models being used by publishers for podcasts.

Not all of this is new, of course. Over the last few years, publishers have experimented with early-access offers (such as The New York Times did for the Caliphate podcast) or member-only podcasts which publishers like The Guardian and more recently, Slate have attempted. Slate Plus, Slate’s membership programme, for example, offers both bonus podcasts and an ad-free listening experience for its members.

Over in the UK, Bauer launched a subscriber-only podcast in 2021, which is a spin-off from their main podcast Empire. The new podcast is published twice a month, and also gives subscribers access to the podcast archive which was previously free.

These are models that should, by now, be familiar to most regular podcast listeners around the world. What happened over the course of 2021 however, is that the subscription business model was turbo-charged by announcements from the two biggest platforms for podcast listening – Apple and Spotify.

In April 2021, Apple unveiled its plans for a podcasts subscription service that would allow listeners to unlock “additional benefits,” like ad-free listening, early access to episodes and the ability to support favourite creators. For publishers, this was a huge deal. As David Tvrdon reports in The Fix, creating a subscriber-exclusive or an ad-free podcast was, up till that point, a complicated, multi-step process involving the creation of unique RSS feeds for each user that had opted to pay. The new Apple Podcasts subscription programme reduces the process to just one click — Apple has the payment information of its customers and can easily charge them.

The Fix also reported that Apple managed to convince some top podcast producers to jump onboard for the launch. Big names include Pushkin Industries, Radiotopia from PRX, NPR, the Los Angeles Times, The Athletic and Sony Music Entertainment.

Great news all around but some caveats that publishers needed to keep in mind about Apple’s plan:

- l Apple will not give podcasters the emails of subscribers, and podcasters can only communicate with their followers and subscribers through the Apple app.

- l Apple will also take a 30% cut of each first year subscription and 15% for following years, just as it does for other subscriptions services. To access the new premium tools, podcasters will be charged $19.99 per year.

- l Pricing starts at around $0.49 per month in the U.S., but creators can set their own pricing. There is no provision to buy individual episodes.

Given that it was a major move by a Big Tech company, you won’t be surprised to hear that the plan wasn’t entirely driven by a need to support struggling podcast creators. “The announcement of the new service follows shortly after an industry report suggested that Spotify’s podcast listeners would top Apple’s for the first time in 2021,” TechCrunch reported.

Sure enough, just weeks after the Apple announcement, Spotify introduced a subscription counter-offer to podcasters, and announced that, unlike Apple, it would not charge them a revenue sharing fee for the first two years. Following this period, podcast producers would be charged a 5% fee for access to the subscription tools.

Though very inexpensive compared to Apple (again, no surprise) the one catch with Spotify’s programme is that if a podcaster wants to use Spotify’s subscription tools, they need to use its podcast hosting platform, Anchor, through which some episodes can be marked as subscriber-only. Still pretty significant news, as Anchor is also the biggest host where podcasters migrate from other platforms, according to the industry newsletter Podnews.

Like Apple, Spotify said the cost to subscribe is determined by the creator, but will be one of three tiers: $2.99, $4.99 or $7.99 per month. In July 2021 Spotify announced 13 pilot partners to test the programme spanning publishers, audiobooks and other creator platforms. The list included Vox Media and Slate from the U.S., Der Spiegel from Germany and France’s Mediapart.

PUBLISHERS CASH IN With the technical ability to offer subscription podcasts now significantly enhanced by Apple and Spotify’s plans, publishers have a significant opportunity to capitalise. We can expect to see paid podcasts go mainstream across the board as 2022 progresses, either as new initiatives by publishers or integrated into existing plans.We already have a handful of examples from Europe, detailed by The Fix.

With the arrival of paid subscriptions on Apple Podcasts the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit set up a paywall around its podcasts on the platform and added audio articles accessible for 5.99 € a month. The publisher has about 19 shows.

Der Spiegel, which offers four paid podcasts as part of a larger audio package, also put those podcasts behind a paywall on Apple podcasts.

In France, while no big publisher adopted the plan, a handful of independent creators, podcast studios and one radio station decided to experiment. The names include Louie Media, Paradiso, Europe 1, Nouvelles Écoutes, Bababam, Binge Audio and Pénélope Boeuf. As we mentioned earlier, the online investigative journal Mediapart was one of the publications chosen by Spotify to pilot its paid podcast programme. The publication was already considered one of France’s most successful digital media outlets in terms of getting people to pay for content.

Over in the U.S, NPR, in partnership with PRX, announced that they would offer an ad-free version of their podcasts to paying subscribers via Apple. Listeners have the option to support a single show and buy ad-free access for a monthly fee, or they could become a member of their local NPR station and get access to all NPR podcasts ad-free. “We continue to feel very strongly that the content we produced should be freely available,” NPR’s Joel Sucherman the Hot Pod newsletter. “We continue to believe in the RSS standard and the open podcast economy. But we feel this is an opportunity for the super fans who really love particular shows to support them at the show level.”

AUDIO ARTICLES — THE POWER OF HABIT Audio articles – the simple exercise of a text article being read out by a human or AI generated voice – have most commonly been seen as an accessibility feature by publishers. In the last two years however, as we have gone through cycles of peak podcast, peak newsletter and audience and product teams trying to work out how and when audiences consume news and in what formats, this seemingly simple feature has had a renaissance and reinvention.

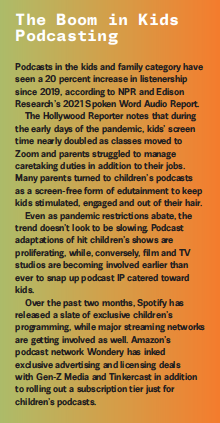

What can we attribute it to? Well, we’ve heard multiplie accounts about the increasing uptake of audiobooks during the pandemic but it turns out that it’s a larger trend with spoken word content. In its third edition, released in November 2021, the Spoken Word Audio Report from NPR and Edison Research, documented how news, podcasts, audiobooks and talk radio’s share of audio listening is at an all-time high. The figures recorded for the U.S. market were stunning: Spoken word audio listening is up 40% in the past seven years, and up 8% year-over-year.

Still, experiments with audio articles are not new and over the years, some publishers have realised that they can play an important role in retaining audiences. As long ago as 2007, The Economist started an audio edition of its weekly magazine, with a voice professional recording every story in the magazine. While only 10% of The Economist’s app users listen to audio, the publisher found that these were the consumers who remained the most loyal. During the pandemic, The Economist saw a record number of streams/downloads and unique listeners, leading them to invest in their audio editions because of the strong, positive impact it has on retention.

“Audio versions of articles allow subscribers to complete issues when they don’t have enough time to sit down and read them,” Deputy Editor Tom Standage told the Nieman Reports. “Our evidence suggests that the audio edition is a very effective retention tool; once you come to rely on it, you won’t unsubscribe.”

Another forerunner in this field is the Danish media company Zetland. Struggling to retain members and subscribers in 2016, the publisher was seeking solutions and the team decided that one possible fix might be to fulfill multiple requests from readers for audio versions of their stories. The pilot was enormously successful — news consumption shifted quickly towards listening to articles rather than reading. The digital analytics firm Twipe reported in 2020 that 80% of Zetland’s consumption is in audio form rather than written text, with numbers accelerating during the lockdown time in Denmark. Zetland found not only that members were more likely to finish the full article in audio form (90% listen-through rate), the format also helped to improve member satisfaction and loyalty.

Were these two publishers on to something big then? In May last year, Press Gazette had an excellent interview with Kat Downs Mulder, Chief Product Officer and Managing Editor at The Washington Post, about the evolution in their audio articles project. In that month, The Post had announced that all of its technology articles would be available to listen to through Polly, a service that aims to transform written text into lifelike speech, on desktop and mobile devices. The Post’s plan was to make more sections available through Polly in the months ahead.

So what’s special about Polly? In July 2020, The Post had made all of its articles available in audio form on Android and Apple mobile devices, using built-in text-to-speech technology on those platforms. Polly, Mulder says, “is a better voice – it’s a smoother, more human-sounding voice. It still sounds like a mechanised voice, an automated voice. But I think it’s a bit smoother and more natural.”

What The Post has hit on there is a solution to the big question around audio articles – human voice or AI? It should come as no surprise that audiences would be more engaged if the article is read out by a more relatable, human sounding voice. The Economist, as we mentioned, had a voice professional read out the articles. Zetland, meanwhile, had the reporters on each story do a voice version. That is of course, infinitely more time consuming than an AI solution and The Post — which has of course been a pioneer in publishing tech in all its years under Jeff Bezos’ ownership — seems to have come up with a winning solution.

Downs Mulder said that Post ‘readers’ have “reacted really well” to its audio offering so far. Subscribers listening to audio articles on its apps “engaged more than three times longer with our content,” she said.

“A big focus of ours is going to be to extend the convenience of the features,” she told Press Gazette. “So not just being able to listen to an individual article, but being able to create playlists of articles, or listen to your saved articles, or listen to all the articles from the front page of the newspaper or from our magazine…”

Like other large publishers, The Post produces a large slate of podcasts. Press Gazette asked if audio articles would be competing against podcasts.

“I think they serve different needs,” Downs Mulder said. “I think it’s a little bit up for debate, how that will end up in the long term. But our podcasts are much more narrative – interviews with reporters, conversations between people, much more highly produced than what you would get through the reading of an article itself. A lot more context.” For audio articles she says, there is “a different use case.”

Other publishers, spotting the opportunity in audio articles, have also looked to AI solutions. The Irish Times, which has had a paywall since 2015, launched “Listen”, a package bringing together all its podcasts and audio articles in one place in 2019. “Initially we did this as an experiment to see how it might work, what was the readers’ feedback and to build out some of the workflows,” Paddy Logue, digital editor at The Irish Times told WAN-IFRA.

A lot of the content on ‘Listen’ was author-narrated which Logue said helped to add cadence and emotion to the narration. But there was a flipside to it. Getting the authors to narrate the article came with a large overhead cost. The stories had to be read out, recorded, edited, processed and so on, altogether creating a big manual process.

With the help of a startup, Speechkit, the publisher started producing AI-narrated articles ”of such good quality that it’s kind of hard to distinguish from human voices,” according to Logue. Partnering with Speechkit, The Irish Times currently produces about 15-20 AI-read audio articles per day.

AI can also help generate specific voices, as the Norwegian publisher Aftenposten attempted in 2021. “We’ve got eight hours or something of speech data and fed it into an AI algorithm that will then generate the voice that sounds like our main podcast anchor,” Karl Oskar Teien, Director of Product at Aftenposten, told The Fix. “She thought it was an honor that she would be the voice of Aftenposten given that we use it for the right purposes.I think it unlocks some other opportunities later on. I think there’s an opportunity to extend the reach of our text content.”

In South Africa, a country with multiple languages and unique accents, publisher News24worked with BeyondWords to create a series of native voices that could pronounce local names in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans. Since adopting these voices for reading out articles the publisher observed a staggering 407% increase in audio engagement compared with publishers using conventional text-to-speech voices.

AUDIO FOR LONG READS In 2020, The New York Times made headlines when it acquired Audm. TechCrunch reported that while there are other services that turn news articles into audio, including read-it-later apps like Instapaper and Pocket, Audm differentiates itself by using professional voice actors to narrate the content, not automated voice technology. That makes the content more enjoyable to listen to — more like listening to a podcast, for example.

In Europe, Twipe reported that we have seen similar platforms such as Curio and NOA that have partnered with leading titles including The Telegraph and The Guardian. The Guardian began their own audio edition in 2012 and since then have vastly expanded their audio offerings with their long-read articles proving very popular in audio form. In Germany, Twipe continues, Audicle has partnered with German-language publishers such as Handelsblatt and Die Gazette to offer quality audio articles.

We end this section with the example of Tortoise Media, launched in the UK in 2019. As the name suggests the company is looking to pioneer ‘slow journalism’, focusing on a few stories and hoping to cut through the clutter. It has already amassed over 110,000 paying subscribers.

Speaking at a WAN-IFRA event in May 2021, Liz Moseley, CMO and Partner at Tortoise Media explained how the company moved to pursuing an ‘audio-first’ strategy.

“What we found is that our journalism, our slow, narrative-led stories, is a formula that lives better in audio than on a small screen as a long-read. It’s kind of obvious now I say it, but it took us a long time to realise that was going to be the case.”

Tortoise mainly uses three audio formats: The Slow Newscast, a weekly investigation of “the stories that really matter.” Members can listen to the Slow Newscast on Mondays, with a free version (with adverts) being disseminated on podcast platforms on Thursdays.

The Sensemaker Daily, which looks at one story every day “to make sense of the world.”

Special investigations, which are published as multi-part series. The most popular recent one is Sweet Bobby, which topped the U.S. podcast charts at the end of 2021.

AUDIO BUNDLES AND STANDALONE APPS With the increasing importance of audio articles added to the mix, it follows that publishers may want to switch focus from individual podcasts and instead take more ownership of the distribution of their audio products by offering bundles. We referred earlier to the ‘Listen’ package offered by the Irish Times as one example of this.

In June 2021, the German publisher Der Spiegel introduced Audio+, its exclusive audio bundle. The package includes an audio version of the weekly edition of the magazine, a daily news podcast (similar to The Daily by the New York Times), a podcast with work-life balance tips and topics on nutrition and mindfulness called CoachingM and “Dein Spiegel Podcast” for children and their parents. The audio package was combined with existing digital offers. All existing SPIEGEL+ subscribers were given a 12-month free access to Audio+. Without the digital access subscription (SPIEGEL+), Audio+ costs 14.99 euros per month, a joint subscription is €19.99. Subscribers can access the paid audio on the outlet’s website or use its mobile app and Der Spiegel also puts the four paid podcasts behind a paywall on Apple Podcasts.

In the same month, Schibsted (the publisher of the Swedish tabloid Aftonbladet and other media) obtained control over the Swedish premium podcast company PodMe which was created in 2017 with an ad-free subscription model and access to exclusive podcasts. The publisher says that audio, which includes podcasts, books, and short-form content, is now a core part of its overall strategy.

Taking the idea of an audio bundle, what if a publication came up with a standalone audio app that could house all of its audio products?

It would certainly be one way of eliminating the middleman, or platform, like Spotify or Apple Podcasts. This intriguing prospect came closer to realisation in October last year when The New York Times announced that it would be beta-testing a standalone audio app called New York Times Audio.

Products under The Times’ banner, including its podcasts, read-aloud journalism, Audm produced pieces and more would feature on the app, Mark Stenberg reported for Adweek. He added that the app would also feature audio journalism from a curated set of publishers, including BuzzFeed News, New York Magazine and Rolling Stone. No financial details of these partnerships were shared, though each of the listed publishing partners produces content on Audm, which, as we noted earlier, The Times acquired in 2020. Another significant purchase made by The Times was that of Serial Productions, arguably the company that kicked off the entire podcast revolution. How’s that for signaling your intentions toward audio?

When The Times decided to beta test the app, Norman Lab reported that it would invite users to give fesempreedback through a survey which had a number of questions about paid subscriptions, and asks users to indicate how much they agree or disagree with statements like, “If one of my favorite podcasts started charging a fee for access, I would stop listening.”

Stenberg, one of the sharpest media analysts out there, has a succinct take:” If The Times builds a standalone audio product that succeeds in attracting repeat listeners, it could mark a new era in the audio industry. The last decade has bred a reticence amongst media companies to rest their content strategy on algorithmically driven third-party platforms, but publishers have largely ceded control of their audio distribution to companies like Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Amazon. In testing the willingness of its audience to seek out its content on a standalone app, The Times is gauging the viability of an owned-and-operated audio product, which could reduce its reliance on intermediaries, as well as offer a host of data and advertising advantages.”

Everything that The New York Times does ends up being pioneering of course, but we should note here that when it comes to a standalone audio product, they were not the first to experiment. The publisher NRC, for example, launched their own audio app in March 2021. Twipe reported that unlike most publishers and public service podcast providers, NRC’s app features external as well as NRC podcasts. The podcasts on the app are editorially curated and feature a range of languages.

Earlier, in 2020, De Correspondent, another Dutch News website launched its own audio platform. Unlike NRC, the content strategy for the publication was on bringing their quality audio journalism to listeners in a controlled manner. While De Correspondent’s podcasts remain available via third-party platforms such as Spotify and iTunes, the new audio platform was created so members could be the masters of their “audio destiny”.

“With more audio stories, we don’t want to become dependent on major listening platforms like Spotify. We’ve noticed they’re trying to make audio more and more exclusive by

buying up big shows and putting them behind a paywall. We want our journalism to remain as inclusive as possible, so we’ve chosen to take our audio directly to you, the members who make it financially possible,” the publication said while announcing the launch of the app.

“Audio journalism and an app are two of the most asked-for features by you, our members, and we’re really excited to now offer both,” the publication added.

LIVE AUDIO – TWITTER SPACES FINDS A SPACE The meteoric rise and even faster fall of Clubhouse, the invite-only app that drove the social media world into a live-audio frenzy in the early months of the pandemic, is now well documented. “More than any other startup, Clubhouse epitomizes the venture-capital-backed euphoria that swept the tech industry since lockdowns shut millions of people inside and pushed them online for connection, entertainment, and information,” Business Insider wrote in a searing article in November 2021. As vaccinations rose and people slowly started to get to grips with life and return to work, interest in the app faded. “Daily downloads of the app have plunged more than 90% since a peak in June, while daily average users are down almost 80% since February,” the piece added.

So did any publishers see opportunities with the platform in its short-lived time as the next big thing? “Currently, few news brands are active on Clubhouse, and the app is facing stiff competition from established social media giants Facebook and Twitter, which are planning their own audio rivals,” William Turville wrote in Press Gazette’s Platform Profile series in April 2021. Various executives Turville spoke to pointed to the fact that the platform didn’t have a large enough audience and there were no clear opportunities for monetisation.

Mike Butcher, the UK-based editor-at-large of TechCrunch who was one of the early adopters, hosting a weekly show on the platform, pointed out that the audio features Clubhouse ‘pioneered’ would eventually find their way to other tools. “So I think our show will eventually work very well on something like Twitter Spaces because it is designed to be very public, for public consumption,” he said.

That prediction did turn out to be rather prescient, because fast forward to March 2022, and a new article in the Platform Profile series was asking if Twitter Spaces could be the future of audio for newsrooms. “Some news outlets using Twitter Spaces see it as a middle ground between a podcast and a conventional social media post,” it said.

The Financial Times for instance, has been using Twitter Spaces since December 2021. “As always with social media platforms, it’s about building awareness of our journalists, content and brand,” FT’s head of social media and development Rachel Banning-Lover said.

“It’s another step on the ladder toward converting them into subscribers. In many cases, the listeners aren’t yet following the relevant FT Twitter account, so we suspect the Spaces are sometimes the first time some people are interacting with the FT.” Similarly, Press Gazette reported that U.K. publication The New Statesman had spent the last few months experimenting with Twitter Spaces, hosting live conversations between a member of its social media team and a journalist where they do a deep dive into a popular article.

“We know we’ve got excellent content, it’s about making sure that we are reaching new audiences. And at the moment, Twitter Spaces is one of the languages on Twitter that can convey our stories,” said Elise Johnson, head of audience at The New Statesman.

Since first starting in December, The FT reports that its average ‘Space’ gets around 300- 400 live listeners, with 3,000 to 5,000 tuning in afterwards to watch recordings. Big topics, like discussions around new Covid variants, can reportedly pull in almost five times as many live listeners.

“We want to retain it as a powerful, yet resource-light tool that journalists can jump on without too much training to dissect an engaging item in the news agenda. A quick way to connect our journalists directly with listeners”

Banning-Lover told Press Gazette.

Eric Zuckerman, head of U.S. news partnerships for Twitter, told Nieman Lab in January this year, that he and his team have been talking to newsrooms about using Spaces for the past year. His pitch? Social audio like Twitter Spaces presents “an opportunity for newsrooms and journalists to have open and authentic conversations with their audiences about what’s happening in the world and about the stories that they’re covering,” he said.

Nieman Lab’s far-ranging piece, written by Sarah Scire, goes on to describe some of the most interesting experiments being done on Twitter Spaces and how the platform is slowly finding its purpose.

“Some of the best Spaces I’ve heard have been where reporters share what they know and what they’re still trying to figure out. When the news broke that Facebook planned to change its name, tech journalists Kara Swisherand Casey Newton held a rollicking discussion with a lot of blue-checked names speculating about what the new name might be, and why Facebook might be interested in making the change,” Scire writes. “The freedom the reporters felt to make some educated guesses — the kind of conjecture that might not make it into print — made it all the more fun.” The article also points to the example of NPR — which has hosted more than 60 Spaces so far — and has also been able to use and reuse conversations hosted on Twitter Spaces. “The reporters open the conversation, talk through recent reporting, and update our audience on what they should know. But I think the real special feature to social audio is the social part, opening the mic to the audience to ask questions that can help us figure out topics we haven’t covered yetor get their reactions to how NPR is covering the news,” Matt Adams, engagement editor at NPR, told Scire.

“I’ve worked in online communities for a long time and before you used to send out a survey to get feedback or ask members how we can better provide a service … To me, social audio is an in-real-time survey where we can gain feedback and hopefully reach new audience members.”

WHAT’S NEXT IN AUDIO? A Many variations in short-form audio or social audio by the looks of it. As mentioned, Twitter Spaces was not the only prominent competitor launched in the wake of the Clubhouse craze though it currently seems to be the live audio tool that’s finding the most cache with journalists and publishers. Along with its foray into podcasts last year, Facebook launched a feature called Live Audio Rooms in June last year to allow users to connect to friends or public figures via real-time audio chats. The company also launched ‘soundbites’, a new creative, short-form audio format that will appear across all their products – an audio version of its Tik-Tok like video product Reels. The latest however, according to reporting from Bloomberg, is that the company is pivoting away from its bets on audio and is focusing on metaverse related products instead.

Another entrant also to watch in this space is Spotify’s Greenroom, which is currently a separate app but is reportedly soon going to be renamed as Spotify Live and become part of the main app. LinkedIn too is getting in on the act. In March 2022, TechCrunch reported that the business and employment-oriented social network was testing a social audio experience in its app which would allow creators on its network to connect with their community. LinkedIn believes its audio networking feature will be differentiated because it will be connected with users’ professional identity, not just a social profile. As yet, there are no prominent examples of newsrooms making use of either of these tools, but given that both platforms have large user bases we are bound to see some experimentation over the coming years.

A host of other companies are also hoping to jump in on the act. “Voice notes and short-form audio have an intriguing opportunity to play a role in the audio future. Or that’s certainly what start-ups such as Beams, Pludo, Quest and Racket are betting on,” Twipe reports. If you haven’t heard of any of those companies yet, we’re with you. But who’s to say we won’t do an entire chapter on them next year. The tech industry analyst Jeremiah Owyang has in fact, identified more than 30 companies working on social audio efforts, calling it a “‘Goldilocks’ medium for the 2020s: Text is not enough, and video is too much; social audio is just right.”

We firmly believe however, that this particular moment in audio still belongs to podcasts and we’re excited to see what comes next on subscription models and standalone audio platforms in particular.

The Innovation in News Media World Report is published every year by INNOVATION Media Consulting, in association with FIPP. The report is co-edited by INNOVATION Presidente, Juan Señor, and senior consultants Jayant Sriram and Inês Bravo