12 Dec Mobile Light Speed is Coming, Get Ready Now

Even as 4G mobile technology continues to be rolled out around the world, work is beginning on the 5th generation (5G) network, which will offer users and publishers previously unimaginable download speeds for media creativity.

Wayne Gretzky, generally regarded as the best hockey player ever, has long been associated with this secret to his success: “I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.” This is not just useful advice for hockey players but as a high-level principle for strategic goal planning.

The global newspaper industry did not move to where the opportunities would be in the 1990s as the Internet began its rapid development and it paid a price for that. Perhaps it can avoid making the same error with one element lurking over today’s horizon: the advent of super-fast 5G ( 5th generation) wireless communication.

5G will succeed today’s 4G (also known as LTE, or Long-Term Evolution) and will permit substantially greater transmission speeds for data (about 50x greater than a typical 20 Mb/s 4G connection) with a fraction of the latency (the time between a signal being sent to another device, such as a server in the cloud, and back to the originating device, or on to subscriber devices). It will use spectrum that is becoming available and will be relatively plentiful, particularly in high density urban areas.

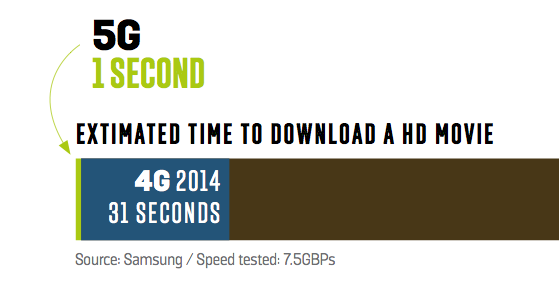

Downloading a two-hour feature film via a 4G connection ( 20 Mb/s) takes over 10 minutes. With 5G ( 1 Gb/s), it could take under five seconds.

At first glance, TV channels, live news broadcasters and movie providers such as Netflix will benefit more from 5G, while the technology would not appear to do much for text-centric outlets: getting words to screens a millisecond faster is not where 5G will help them, but ‘newspapers’ are incorporating more video, image and audio in their feeds than ever before, as a more multi-media model emerges of how users want their news in the second decade of the 21st Century.

And the extent of previously non-obvious advances from new technologies has been seen time-and-again. When Apple introduced its iPhone, not even Steve Jobs could have predicted the tens of thousands of types of applications that would follow, from Twitter to Shazaam to SnapChat and beyond.

Virtual & Augmented Reality

Media outlets currently experimenting with Virtual Reality (VR) might have a head start. The New York Times, The Economist, Gannett’s Des Moines Register, The Wall Street Journal and the Times of India are among the pioneers in this space, and the time it takes to download the large files created for a VR story is one of the barriers to its widespread use (the costs of creating the pieces is a separate obstacle). With a 5G connection, viewers could download or stream a VR report as quickly as they get the text of an article today.

VR plays to the content gathering and editing strengths of newspapers. The New York Times’s Ben Solomon and Leslye Davis hold that “As journalists, we always seek to help readers understand what life feels like in the places we cover. Virtual reality allows us to do that in an entirely new way.” Referring to a piece published less than a week after the November 2015 terrorist attack in Paris, they said that: “Using this medium, we aimed to create a more textured experience — the streets of Paris distilled to voices and spaces. Although the technology is evolving, it’s clear that this new frontier can soon become a crucial journalistic tool”.

Advertisers already see value in VR as a way of improving consumer involvement with their

products. In April 2016, Tata Motors provided an insert in the Times of India that included a customised Google Cardboard VR headset and instructions on how to download an app with a VR demo of its Tiago model. This provided the newspaper’s audience with a free, if primitive, VR viewer, following a similar New York Times promotion the previous autumn.

But the confluence of VR devices and 5G is just one way newspapers may find opportunity from the next iteration of wireless technology. While less immersive than VR, Augmented Reality (AR) may have greater everyday value for publishers. Whereas VR ideally takes one totally into another environment (hence the headsets, earphones and even touch sensors employed), AR is an overlay on the real world (think of the heads-up displays used in fighter jets). A communications link provides real time data to the user. Google Glass was an early AR experiment. “Everything about VR is hype”, said Ron Diorio, VP of Business Development and Innovation at The Economist: “the danger is in mistaking the hype for the story”. That currently applies to the promises made about 5G and AR. “A lot of this 5G is about carriers and equipment makers looking for new ways to make money”, said Thomas Husson, an analyst at Forrester Research in Paris. Yet no one denies 5G will happen, it’s just a question of when; widespread use after 2020 seems to be the consensus. News publishers can begin to think creatively about the possibilities by looking at what other industries might do with 5G.

Time to think creatively

WordLens, an application for smartphones, translates between languages by using real-time imagery from the camera (not a photo)—such as the annotation for a sculpture at a museum—to present the user with the same image but with the translated text. A future iteration, using a device such as Microsoft’s HoloLens and a new generation of Google Glass. might allow a user to look at that translated text on a hologram of the object being observed instead of the computer- like screen in the first version of Google Glass.

So if 5G allows for real-time holograms, imagine an image of a conventional newspaper a reader could flip though by making page turn gestures. Beyond that, subscribers could access a deep array of news-based real-time and archive data as they interact with the world around them. Medical applications, connected in real time to the Internet of Things (IoT), offer another industry that might provide creative suggestions. Millions of wireless devices, ranging from the already familiar fitness monitors to smart watches and sensors embedded in industrial products, may be connected via mobile networks instead of the far more limited Bluetooth technology we often use currently. Sensors embedded in clothing could monitor heart rhythm, sending data to servers that could spot early warning of a problem and even alert an appropriate medical professional. Diabetics could similarly have improved observation and be warned of impending issues before they are physically aware of a problem.

Then there is 5G and sports. Ericsson, the world’s largest telecoms gear vendor, has collaborated with a manufacturer of sports equipment to develop a bicycle helmet that smart cars can sense, reducing the likelihood of car-bicycle collisions.

You’re still in time

In the US, Verizon and AT&T, have announced test sites for 2016 and at least the start of a roll-out in 2017. In Russia, wireless operators MegaFon and MTS are expected to test 5G-style services in time for the 2018 World Cup in that country. Korean mobile operator KT also plans to offer its version of 5G at the 2018 Winter Olympics there. Not to be outdone, Japan’s NTT DoCoMo says it will have similar trials ready for the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

As with the organic development of the smartphone app universe, it would be folly to be too specific about predicting how the Internet of Things might be used by newspaper publishers. At the not-so-radical end would be the use of sensors in printing presses to improve real-time efficiency and performance to reduce newsprint waste. Sensors, like improve RFID tags, could be employed in distribution to better understand the real-time whereabouts of each delivery component and to aggregate “big data” to improve the logistics of hard copy delivery.

A more futuristic scenario might employ big data to help advertisers do Augmented Reality real-time, fully contextualised ads. A department store today advertises in the newspaper based on the general demographics of its readership, and the online version might know a bit more about what sites the user has visited previously. Fast- forward to the 5G world, and imagine the same buyer wearing the eye glasses of the future, with embedded micro visual sensors that record what that user is looking at. Imagine he is looking at a pair of jeans in a store or on a screen. Our 5G department store could immediately send a text message with a special offer directly on to the customer’s heads-up display in the glasses, or the precise directions to the nearest store where he could purchase a pair.

This kind of scenario and the possibilities of the Internet of Things obviously raise privacy issues and will require new research into user relations and opt-in requirements.

5G is not there yet. Standards must still be agreed on and carriers will need years of changes and billions of dollars of investment, but the implications could be very far ranging and disrupt more than one industry. 5G is generally thought of as a mobile service but in high- density urban areas it could replace the wired ISP most households use, although mobile data consumption is already greater than fixed data in many locations around the world. If mobile carriers can convince health care companies, transport firms and media outlets to connect their sensors and broadcast over 5G, they might generate a new revenue stream of revenue to help pay for the capital investments needed to deploy it.

INNOVATION’S TAKE

Recent college dropouts in garages or bedrooms in Silicon Valley—and its smaller counterparts around the world—are doubtless already mulling over the opportunities 5G will offer and sketching out ideas on napkins. Publishers and editors should keep an eye on them and their ideas. Early versions will fail or morph into something new but if we’re not in the game, we’re never going to win. In this case, slower media companies who need longer to adapt are still in time to start thinking about the new opportunity.

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovations in News Media 2016 World Report.