30 May Best Practice for Setting up a Fact-Checking Unit Within Newsrooms

Research from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in Oxford University shows a powerful shift back to news organisations as a primary source of information during the pandemic. The Reuters Institute Digital News Report of 2021 notes that in many countries, audiences are turning to trusted brands – in addition to ascribing a greater confidence to the media in general. “The gap between the ‘best and the rest’ has grown, as has the trust gap between the news media and social media. Debunking false or misleading information is one of the key ways in which this trust can be built and it is a key part of shifting readers toward valuing the expertise that news organisations can bring. Correcting misinformation, whatever the source, can be critical to building reader trust in reporting.

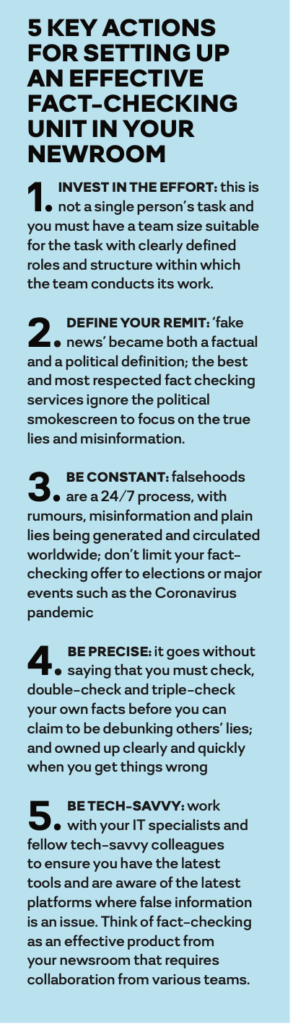

While there has been a proliferation of independent fact-checking organisations over the last several years, fact-checking units attached to newsrooms enjoy some significant advantages. Media companies are able to assemble audiences which vastly exceed the reach of most independent fact-`1!~wacheckers and they are also able to draw on the editorial resources and infrastructure of a larger news-gathering operation. A number of newsrooms have made impressive commitments and dedicated vast resources to setting up fact-check units as we detail here:

Der Spiegel – Germany

The German news outlet Der Spiegel runs what is perhaps the biggest fact-checking unit inside a newsroom. About 70 people work full time in fact-checking and research at the publication’s research library and the department is called “Dokumentation”. The fact-checking operation is not new and is a detailed process that dates back to the 50s, a few years after publication of the print magazine started in 1948, and is now integrated into editorial workflow. The Dokumentation team is organized by expertise that mirrors the publisher’s different desks, such as politics, science, economics, foreign affairs, culture and sports. These specialists often have doctorates in their fields of expertise, Digiday reported in 2017.

Members of the team often work with journalists on articles, providing them with relevant research. In that sense, they have a dual role within the newsroom. “There are two main purposes of our database. The first is to do the research in the process of preparing articles. The writers department calls us up or sends us an e-mail or comes by our office, and we develop a plan of what materials are needed to research and write articles. In a way you could say that during a working week, the first three days, from Monday to Wednesday, we are researchers and Thursday and Friday we are fact checkers,” Axel Pult, a former checker now the deputy head of the department told the Columbia Journalism Review in 2020. The backbone of Dokumentation is a database of text articles and official information about notable people, enterprises or topics that could be useful for the journalists at Der Spiegel. Each week, the database automatically adds another 60,000 articles from German and international media and other official sources like government documents.

Grupo Globo, Brasil – ‘Fato ou Fake’

The Brazilian media giant Globo runs Fato ou Fake (Fact or Fake), an effective factchecking service as part of its digital news offer to alert its audience about dubious content disseminated on the internet. The project brings together resources from eight different newsrooms — G1, O Globo, Extra, Época, Valor, CBN, GloboNews and TV Globo — which are part of the conglomerate. About 80 journalists who are involved full or part time in the project monitor social networks, checking messages with wide dissemination. The monitored information is classified by seals: “Fact”, when the content is completely truthful; “Not quite” when it is partially true and requires clarification; and “Fake”, when it does not have proven data. In November 2020, at a time when misinformation on Coronavirus was rampant, Fato ou Fake launched an exclusive bot on WhatsApp to allow Brazilians to request the checking of content disseminated through the web and on cell phones.

Once a person messages in they will have a menu available, where they can choose between 4 options. By selecting option 1, the person can send a suspicious link, text, photo, audio or video for analysis. With option 2, the person will receive the last checks made by Fato or Fake and, when entering option 3, the last checks only related to the Coronavirus. The person will also be able to select option 4 and watch a video where tips are given on how to identify a fake message.

Jagran New Media (India) – Vishwas News

Vishwas News is the fact-checking unit of Jagran New Media, the digital wing of Jagran Prakashan Ltd. which publishes Dainik Jagran, the largest newspaper in India by circulation. Vishwas News started as the first Hindi language fact check site in 2018 and has since expanded into several other languages. The fact-checking unit is a separate desk with separate SOPs, editorial guidelines, and work ethics, Pratyush Ranjan, senior editor at Jagran New Media in India, told an INMA conference in May 2020. Vishwas news works with a highly structured process, starting from a morning meeting where trending topics are discussed and the day’s stories to fact-check are decided. The team then begins investigation and physical verification of quotes or facts if needed before stories are published every day. Vishwas News also works with the International Fact Checking Network as one of 73 IFCN- certified fact-checkers around the world. It also partners with WhatsApp to counter Covid-19 disinformation and with Twitter to identify fake tweets. It is also a third-party Fact Check Partner with Facebook in India (operating in four languages) and with ByteDance (Helo and TikTok) for a limited number of posts in six languages.

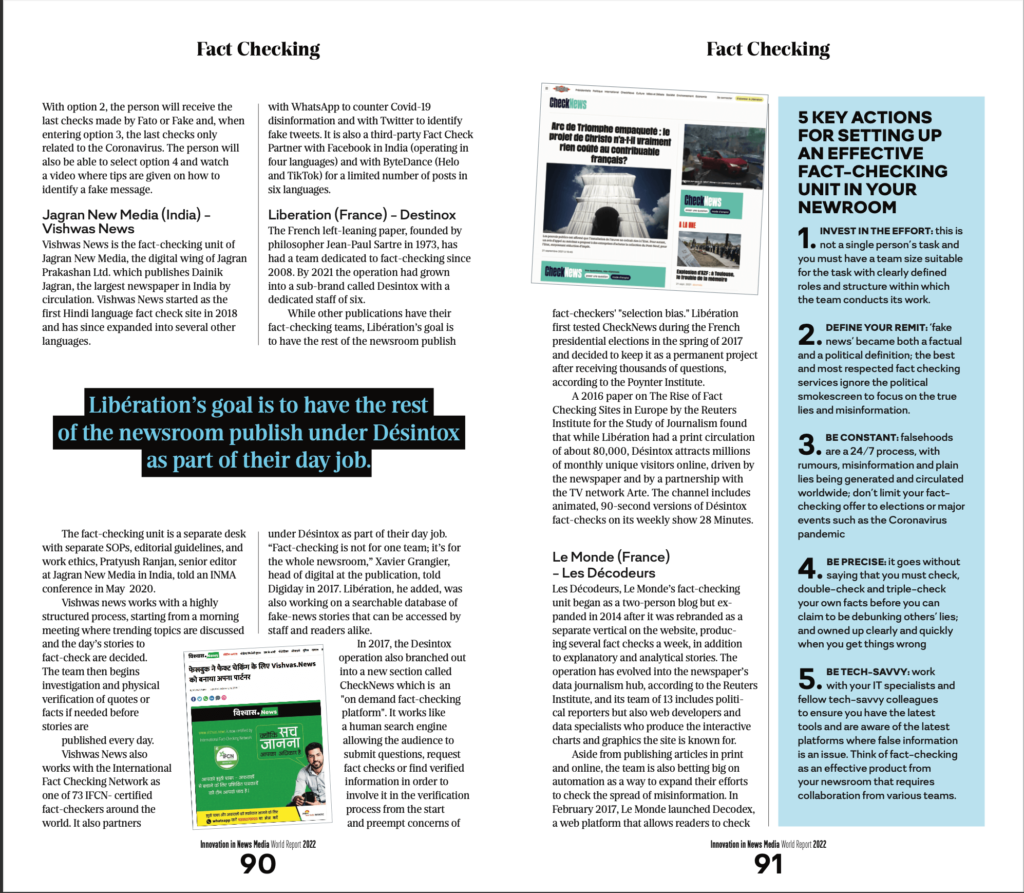

Liberation (France) – Destinox

The French left-leaning paper, founded by philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre in 1973, has had a team dedicated to fact-checking since 2008. By 2021 the operation had grown into a sub-brand called Desintox with a dedicated staff of six. While other publications have their fact-checking teams, Libération’s goal is to have the rest of the newsroom publish under Désintox as part of their day job. “Fact-checking is not for one team; it’s for the whole newsroom,” Xavier Grangier, head of digital at the publication, told Digiday in 2017. Libération, he added, was also working on a searchable database of fake-news stories that can be accessed by staff and readers alike. In 2017, the Desintox operation also branched out into a new section called CheckNews which is an “on demand fact-checking platform”. It works like a human search engine allowing the audience to submit questions, request fact checks or find verified information in order to involve it in the verification process from the start and preempt concerns of fact-checkers’ “selection bias.”

Libération first tested CheckNews during the French presidential elections in the spring of 2017 and decided to keep it as a permanent project after receiving thousands of questions, according to the Poynter Institute. A 2016 paper on The Rise of Fact Checking Sites in Europe by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that while Libération had a print circulation of about 80,000, Désintox attracts millions of monthly unique visitors online, driven by the newspaper and by a partnership with the TV network Arte. The channel includes animated, 90-second versions of Désintox fact-checks on its weekly show 28 Minutes.

Le Monde (France) – Les Décodeurs

Les Décodeurs, Le Monde’s fact-checking unit began as a two-person blog but expanded in 2014 after it was rebranded as a separate vertical on the website, producing several fact checks a week, in addition to explanatory and analytical stories. The operation has evolved into the newspaper’s data journalism hub, according to the Reuters Institute, and its team of 13 includes political reporters but also web developers and data specialists who produce the interactive charts and graphics the site is known for. Aside from publishing articles in print and online, the team is also betting big on automation as a way to expand their efforts to check the spread of misinformation. In February 2017, Le Monde launched Decodex, a web platform that allows readers to check whether a website is reliable or not. Décodex allows readers to search a database of around 1,000 websites and social media profiles, Nieman Lab reported back in 2017, up from about 600 at launch. The idea is that once a user has downloaded the extension, when they come across articles online a red flag will appear if the site or news is deemed fake, yellow if the source is unreliable or green if it’s ok. Sites are divided into four categories: those that regularly disseminate false information; those that are unreliable (occasionally publishing fake news, not citing sources); satire; and reliable. There is also a facebook Messenger bot that users can ask to either verify a site or search for information on hoaxes that Le Monde has debunked.

BBC (UK) – Reality Check

In 2017 the BBC made Reality Check, a fact-checking service set up during the EU referendum campaign, a permanent feature of its news coverage. The service works with social media sites such as Facebook to combat “deliberately misleading stories masquerading as news”, according to a statement released by the broadcaster. “We want Reality Check to be more than a public service, we want it to be hugely popular. We will aim to use styles and formats – online, on TV and on radio – that ensure the facts are more fascinating and grabby than the falsehoods, ” director of news and current affairs James Harding said at the service’s launch. Both Facebook and the BBC are signed up to the First Draft Partner Network, a coalition of platforms and publishers that work together to provide guidance in how to verify content sourced from social media. According to Press Gazette, the BBC’s Reality Check team scrutinises stories that are heavily shared on Facebook, but are not true and are not from authentic news sites. When they spot a story, the team will attempt to verify or fact check the claims it makes and then publish an explainer or a corrective piece that can be read and shared.

The Washington Post (USA) – Fact Check Column

The Washington Post’s fact-check column came into prominence during the Trump years in the U.S with its now famous Pinocchio rankings of false statements. The Post’s fact-checking operation first started on Sept. 19, 2007, as a feature during the 2008 presidential campaign and it was revived as a permanent feature. Since then the fact-checking operation has been centred around one major personality — veteran journalist Glenn Kessler who has been the editor and chief writer of The Fact Checker. “The purpose of this website, and an accompanying column in the Sunday print edition of The Washington Post, is to “truth squad” the statements of political figures regarding issues of great importance, be they national, international or local. It’s a big world out there, and so we rely on readers to ask questions and point out statements that need to be checked, Kessler wrote in 2017. “But we are not limited to political charges or countercharges. We also seek to explain difficult issues, provide missing context and provide analysis and explanation of various “code words” used by politicians, diplomats and others to obscure or shade the truth,” he added.