03 Dec Why Fake News Will Save Journalism

‘Fake news’ became a hot topic of conversation in 2017. Although it is a phenomenon that has quite rightly led to widespread concern, it is also arguably the best thing to happen for serious journalism for some time.

Fake news highlights both the risks of relying on unreliable sources, and the need for well-funded journalism that can play a fact-checking as well as a watchdog role. Publishers should therefore seize the opportunity to present their news as the trustworthy alternative to misinformation and see this as an opportunity to grow their businesses.

The phrase ‘fake news’ is controversial in itself. Several analysts and experts from within and outside the media industry refuse to use it in favour of descriptions such as false news or misinformation. It is important to note the worrying trend which has seen the term used by powerful figures such as President Trump to describe news which they find merely distasteful – whether because of political differences or because it is overly sensationalist, for example.

For want of a better alternative, for the purposes of this article, ‘fake news’ refers to deliberate misinformation or disinformation posing as news, either for financial or political gain (or both).

The Danger

Fake news is seen as particularly dangerous around elections, and it is its potential impact on the democratic process that has understand- ably caused most concern. A key example is the fictitious ‘Pope supports Trump’ story that was circulated shortly before the 2016 US presidential election. Originally published by a two-week- old fake news site with the goal of bringing in advertising revenue, it was adopted by Trump- supporting sites as a political tool, and ended up with more than a million Facebook engagements when posted on the site by a right wing organisation. It’s the sort of story that could influence voters for whom the Pope’s views hold a great deal of weight.

Many believe that deliberately misleading ‘news’ will only become more pernicious as video and audio manipulation improve: it is now possible to make videos which seem to quite literally put words into people’s mouths, making it appear that someone has been caught on video saying something that they did not. This is likely to be more convincing to much of the public than reading a story.

The Opportunity: Shining A Spotlight on Social Media and Search

The impact that fake news has had on the public image of tech companies, particularly Facebook, is far-reaching and its extent is not yet clear. For Charlie Beckett, media and communications professor at the London School of Economics and the director of Polis, fake news is ‘the canary in the digital coal mine:’ it is an early indicator of a wider crisis in public information.

The spread of fake news has put the level of influence that social media companies hold over both publishers and content consumers under the spotlight of public discussion, and Google, Facebook and other tech companies have come under a good deal of criticism from industry, policymakers and civil society for their role in spreading false and inaccurate information, as well as for contributing to the business model crisis that news outlets are facing by dominating the online advertising market.

This increased attention has made tighter regulation of these tech giants seem a distinct possibility, even in traditionally liberal markets. In the UK, for example, a parliamentary select committee is looking into fake news and its effect on society. In the US, Congressional committees grilled representatives from Facebook, Google and Twitter in early November 2017 as they investigated Russia’s online information operation, and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was called before Congress in April 2018 in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica revelations. A European Commission consultation into fake news and online disinformation run from late 2017 to early 2018 received almost 3000 responses.

The public are also increasingly skeptical: the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report found that just 24 per cent of global respondents believed that social media does a good job in helping separate fact from fiction.

Tech Companies’ Response

Facebook and Google have responded – whether due to the threat of regulation, or because of a desire to take more responsibility for their increasingly significant roles in society – with various efforts aimed at tackling the most common com- plaints about the way that they present content.

Facebook released advice to users on how to spot fake news stories and has started to show ‘related articles’ in Newsfeed in an attempt to encourage users to read beyond the sources that they already follow and break out of the ‘filter bubble.’ Facebook’s product manager in charge of civic engagement has publicly asked and discussed ‘what effect does social media have on democracy?’ and outlined the ways in which advertising on Facebook is becoming more transparent and accountable.

Google enabled a “Fact Check” tag in Google News for news stories which claims to identify “articles that include information fact checked by news publishers and fact-checking organizations.” The tech giant has also attempted to reduce the number of misleading and offensive results that appear in its search engine, by improving “evaluation methods” and making “algorithmic updates to surface more authoritative content.” It has also started allowing users to report inappropriate content.

As noted below, the tech companies have also started funding fact-checking initiatives.

Changing Business Models

The focus on ‘fake news’ has also further exposed the flaws in the programmatic display advertising model, whereby advertising is sold through an ad network or platform on the basis of how many clicks or views it will receive from a target demo- graphic. This type of advertising is largely seen as fueling the spread of fake news, and means that neither advertiser nor publisher knows which ads will be shown where, and therefore ads might be shown alongside fake news without the advertiser even knowing.

Large companies who use a good deal of online advertising are fighting back. British multinational telecommunications company Vodafone announced new rules last summer to prevent its advertising from appearing within outlets focused on creating and sharing hate speech and fake news, via a whitelist-based approach using content controls implemented by Vodafone’s global agency network (led by WPP), Google and Facebook. The world’s two biggest advertisers – Dutch transnational consumer goods company Unilever and American multinational Procter & Gamble – have threatened to pull advertising from platforms like Facebook and Google if the companies don’t do more to stop hate speech and harmful content such as misinformation.

This distrust in the online advertising market provides an incentive for publishers to focus on subscriber revenue more than ever, and means therefore that their high quality journalism is more important than ever.

Several U.S. news media have seen a jump in subscribers since the election of Trump and the spread of fake news: according to the 2017 Reuters Digital News Report, the percentage of people paying for online news is now 16 per cent, up from nine per cent the previous year, along with a tripling of news donations. Including subscriptions for its crossword and cooking products, The New York Times, for example, now has nearly 2.5 million digital-only subscriptions, and digital-only subscription revenue overtook print advertising revenue for the first time in the second quarter of 2017. The Wall Street Journal and Washington Post also saw significant growth in subscriber numbers from the end of 2016 onwards.

Reviving Trust

According to WAN-IFRA’s 2017 World Press Trends, “it is clear that for our industry, the demand for trusted news sources represents a business opportunity.” Edelman’s Trust Barometer did show an increase in trust in journalism in 2018, to 59 per cent, alongside a drop in trust in platforms (to 51 per cent).

However, the Reuters Digital News Report found that around 40 per cent of people thought that the media does a good job in helping separate fact from fiction, which is more than those who trusted social media, but is still a rather low percentage. Trust in news media remains lower than it could be in many countries around the world, and news organisations must embrace the challenge of restoring faith in their brands and their journalism.

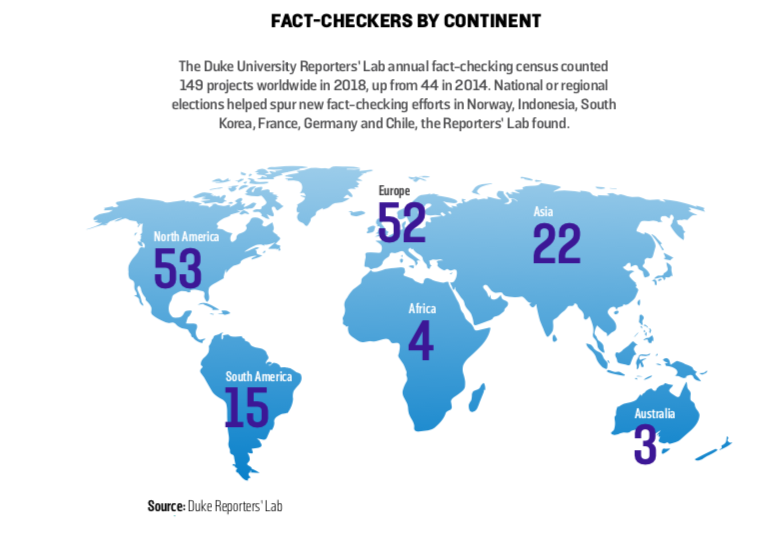

Growth of Fact-Checking

Clear fact-checking and debunking of fake news are important parts of news media’s effort to maintain and regain trust. Various initiatives have been launched by news outlets, tech companies and other organisations around the world in recent years; some specifically targeting election campaigns while others have a more general focus.

Some examples of initiatives within news organisations include:

• BuzzFeed has embarked upon a significant effort to identify and debunk fake news and misinformation, and to highlight the extent of the problem. Its wealth of reporting on these issues includes pieces on make your own fake news sites and misinformation spreading about the UK general election.

• Les Décodeurs from Le Monde is working on how to automate the detection of fake news. According to a Digiday article, “The plan is to build a hoax-busting database, which incorporates information on which sites are fake and which are verified, trusted sources, and readers can access via Google and Firefox Chrome extensions”.

• Reuters has launched a News Tracer which uses algorithms to detect which stories on social media might be newsworthy and to start the verification process, which is then completed by a journalist.

• BBC Reality Check describes itself as “dedicated to examining the facts and claims behind a story to determine whether or not it is true.” The site invites readers to fill in a form to offer ideas of topics to investigate, which could be stories they have seen that look suspicious, or just something that they have always wanted to know the truth about.

Several partnerships between traditional news organisations and startup or academic initiatives also exist:

• Faktisk is a collaboration between (rival) Norwegian news organisations VG and Dagbladet and the public broadcaster NRK, with the mission of fact-checking the media, as well as politicians. The collaboration is a reflection of how seriously news outlets are taking the problem of false news, participating journalists told Poynter.

• First Draft Crosscheck (funded by Google News Lab) was a collaborative verification project that aimed to help voters to make sense of what and who to trust online ahead of the French presidential elections in April/May 2017.

• Factmata, funded by Google and based at University College London and University of Sheffield, hopes to launch “a state-of-the-art fact- checking system using machine intelligence, for statistical claims made in digital media content, such as news articles and political speech transcripts,” according to its site.

• The News Integrity Initiative, funded by Facebook and based at City University New York, is a network of partners working together on news literacy and addressing “misinformation, disinformation and the opportunities the internet provides to inform the public conversation in new ways,” according to Facebook’s head of news partnerships, Campbell Brown.

And there are new independent projects, such as:

• WikiTribune is a new initiative from Jimmy Wales that aims to bring the crowd-funded, open access principles of Wikipedia to a news outlet, with stories that are ‘easily verified and improved.’

Funding for such initiatives has coming from within news outlets, from philanthropic organisations, and from tech giants Facebook and Google. Not all publishers have the resources to build technically complex tools, but many could include more fact-checking and debunking in their day-to-day work, or build partnerships to make it easier and more efficient.

Beyond Fact-Checking

Fact-checking is a vital service but it’s not the only thing that news organisations can do to fulfil their obligations to their audience and retain their trust and with that, their attention. The 2017 Reuters Digital News Report found that the biggest reason that the public doesn’t trust the mainstream news media to distinguish fact from fiction is the sense that people have that news has bias or an agenda (cited by 67 per cent). As report author Nic Newman asked, will fact-checking and news literacy efforts be enough to convince those who feel the media has an agenda?

Transparency, for a start, is crucial in gaining and keeping readers’ trust. This could include, for example, publishing full transcripts of interviews when appropriate, as The New York Times has done when interviewing President Trump. The American investigative documentary series Frontline from PBS decided to preempt any allegations of biased editing of its documentary on Putin and his attitude to the US by making all 70 hours of the interviews done for the show available online. As Poynter highlighted, a series by Steven Brill published in the Huffington Post, “America’s Most Admired Lawbreaker,” included all documents used, including deposition transcripts and emails, to help readers see if the story used them in proper context.

Diversity and more accurate representation of readers both among staff at news organisations and in the stories that they cover are also crucial, so that outlets are less likely to be perceived as being out of touch and run by an elite from whom many people feel alienated. Particularly when targeting subscriber revenue, it is vital to build connections with the audience, and not to see it simply as a homogenous body, but to appreciate and cater to its diversity. The Guardian’s 2017 project Inequality and Opportunity in America is a good example an effort to increase diversity in reporting: it included publishing writers from rural areas across the U.S. in collaborations with local newsrooms.

Powerful branding is also important. Edelman’s 2018 Trust Barometer found that 59 per cent of respondents believed it was getting harder to tell if a piece of news was produced by a respected media organization. News outlets need to find ways for their content to be easily identified even when it’s not always being found on their own sites.

The Bottom Line

Fake news provides the opportunity for good journalism to shine, and for news providers to strengthen and build upon their trusted brands.

Rather than joining the panic over what fake news means for society, publishers should be focusing on fighting back with high quality journalism, differentiating their valuable products from the abundance of misinformation to be found online. The growing distrust of social media only leaves more room for publishers to gain and retain loyal readers. And despite President Trump’s criticism of the news sources of which he doesn’t approve, the public hasn’t stopped buying their papers and watching their news.