08 Oct Digital Narratives: The Golden Age of Storytelling will only be golden for some

Media companies who employ the best of storytelling tools will win audiences; everyone else will shrivel and many will die.

This is the Golden Age of Journalism

But perhaps not for you.

You’ve heard the phrase before, and you’re probably sick of slick slogans like that.

But, aside from being over-used, too cute, and more than a wee bit too optimistic, it also happens to be true.

Content creators have never had more tools at their disposal to tell stories more completely and compellingly. The Golden Age of Journalism keeps getting more golden every day.

But not for everyone.

The age will only be golden for those media companies that employ the new tools and platforms in ways that keep pace with their own particular audience’s adoption of the new technologies.

Why?

Because the tsunami of content — “peak media” — has reached a point where consumers can be very picky about what content they choose to consume. With limited time, they will only choose the sites that use the most rewarding, unique, engaging, entertaining, efficient, informative, and convenient storytelling tools on the platforms they prefer.

Media companies not only have to master new storytelling tools, but they must also blow up their old cultures to create fertile ground for making the most of the new tools. Without an innovative culture, all the skills in the world won’t matter.

This is not so much an arms race, but a creativity and targeting race.

Placing too much emphasis on the storytelling technology itself is a mistake, according to John Peeters, business development director at the Holition digital creative studio which specialises in emerging technologies.

When asked which forms of technology publishers should specifically be looking to add into their strategic portfolio, Peeters warned against the idea of loading up on tech.

“They should not look to technology,” Peeters told us. “They should use their imagination. “I hope there are people in the publishing business and the wider media business who use their imagination and who use [it] to come up with something new and revolutionary,” he said. “Think about the unthinkable. And if that makes sense somehow, then try to build it. And not, ‘Hey, this is a piece of tech what can we do with it?’”

So, what are the new and emerging storytelling tools we can use imaginatively to differentiate our content, keep our existing audiences, and attract new ones?

What could be more natural than listening to someone tell a story?

Whether it’s podcasting or creating standalone audio stories or building a “skill” for those voice-activated gadgets like the Amazon Echo, audio stories have attracted growing audiences across the globe.

At the Washington Post, a media innovation leader since being purchased by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos in 2013, audio is top of mind.

“We are thinking deeply about audio, the Amazon Echo and Podcasts,” Post Director of Strategic Initiatives Jeremy Gilbert, told us. “The opportunity to go from being a text-based media company to one that releases its own audio is very important to us.

“We are most proud of both serious and compelling content and also the way that we push the boundaries of technological innovation in media, too,” Gilbert said.

In addition to podcasting (which we’ve covered in depth in earlier Innovation reports), there are a lot of audio initiatives happening around the world.

In addition to podcasting (which we’ve covered in depth in earlier Innovation reports), there are a lot of audio initiatives happening around the world.

In Portugal, legacy media company Público is actually looking at a “pivot to audio”, according to their editors. To deepen their relationship with their audience, Público is beta testing “P24,” a personalised audio catch-up format.

Público’s data told them that their readers were only spending a few minutes with them every day. So they developed a personalised daily audio digest — P24 — that is around ten minutes long. “This product was made to serve the kind of users we already have, but we wanted to serve them better,” Público’s Innovation Coordinator João Pedro Pereira told the Global Editors Network.

“P24 [brings] our journalism into moments of people’s lives which are not typical moments that they would be with us. We can be with people when they’re at the gym, in their cars, or washing their dishes.”

Users can personalise their own digest by choosing topics, and the final product is created by both algorithm and editorial curation.

Público secured a top-tier sponsor — BMW — from the beginning. “They wanted to join precisely because of the innovation factor, not big audience numbers,” Deputy Editor Diogo Queiroz Andrade told Global Editors Network.

“We believe that audio interfaces are growing, so we are betting on them to become very relevant,” Andrade said. “Not in Portugal yet — mostly in Anglo-Saxon markets — but we know they will grow here, too. We want P24 and our whole audio offering to be sustainable. We want to be a reference in terms of audio in Portuguese news and we want P24 to lead that.”

We cover voice-activated personal assistants in detail in the Tech Chapter (see page 74), but here’s another example worth mentioning.

In late 2017, the BBC unveiled an interactive audio sci-fi comedy called The Inspection Chamber built exclusively for Amazon’s Alexa. The twist is that listeners must use their own voice to become a character in the story who can then change the course of the narrative.

“Our hunch was that direct conversation that changed the details of a story would be more satisfying than making choose-your-own-adventure style choices — playing a part, rather than directing the action,” BBC R&D senior producer Henry Cooke told The Global Editors Network. “We wanted to make it feel like you’re having a genuine, direct interaction with the other characters in the piece,” Cooke wrote in a BBC blog. “We haven’t come across any other interactive stories like this on voice devices, and we’re excited to see how people respond to it.”

The editors built the story around short segments with frequent questions because, Cooke said, voice devices like Alexa are not built for long-running conversations as entertainment. With this program and other audio experiments, Cookie said the BBC will examine the types of content that work well on smart speakers and accordingly create new experiences that are tailored for these platforms.

Discovery and accessibility have been challenges for audio content.

“There are a lot of opportunities for audio content and different kinds of audio services on a smartphone,” Paula Cordeiro, founder of Portugal-based multi-media design and tech brand Urbanista, told us. “I really don’t know why this isn’t happening faster. Maybe Google and Facebook are to blame because they don’t make it easy to share audio content online.

“If I want to search for a podcast, I have to use different kinds of words,” Cordeiro told us. “I can’t search for audio on Google. If you post audio on Facebook and you don’t have an image, then nothing happens. And so maybe this is part of the problem — not exactly the real problem, but something that would help audio move more into the mainstream would be to have these huge platforms getting into audio more.

“But audio for them is just awkward,” Cordeiro said. “They don’t know exactly what to do with it and I think that audio people, radio people and the broadcasting industry should make a move into educating people from other industries, such as advertising industry agencies and brands, on how powerful audio can be to their story.” Given this discoverability challenge, people took notice when the Guardian in the UK started experimenting with web-based audio story delivery. Alastair Coote, a developer at the Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab, created a web-based mobile player on the Guardian’s website by embedding a media player in Chrome to make their mobile content easier to find and to play.

And then, to maintain a connection with listeners, Coote built a subscription option so fans can choose to be alerted by push notification when a new episode has been created. “It’s been fascinating to see how easily you can build an audience on the web when you remove the barrier of having to download and use an app,” wrote Coote on the Guardian Lab’s blog.

Breaking audio, especially podcasts, out of dedicated platforms and apps enables listeners to avoid having to download those apps or activate them to listen. A web audio piece represents a much more discoverable, more streamlined user experience.

2. Automated or Robotic Journalism

Nothing strikes more horror in the hearts of journalists than robotic reporting.

However, once writers and editors get past the vision of an editorial department full of robots and hear about all the drudgery robots can take off their plates, horror is replaced by curiosity and cautious acceptance.

And when media executives discover that robots can create content in areas the company doesn’t have the resources to cover — thus providing “plus” content — they, too, want to know more about robots.

In mid-2016, The Washington Post launched its purpose-built artificial intelligence technology (Heliograf) to create robot-written stories. Since then, The Post has produced 350 short reports and alerts on the Rio Olympics, hundreds of reports on congressional and gubernatorial races, and hundreds of local school sports stories, Post Director of Strategic Initiatives Jeremy Gilbert told Digiday.

Most of these stories would not have been covered otherwise, Gilbert said. In elections prior to 2016, Heliograf didn’t exist. In 2016, The Post used Heliograf to generate almost seven times the number of stories, according to Gilbert.

And those stories weren’t just statistics. The Post’s editors create story templates, including standard wording to cover a variety of possible outcomes such as “Republicans retained control of the Senate” or “Democrats re- gained control of the House”. When the election rolled around, they connected Heliograf to data sources (for the election, it was data clearing- house VoteSmart.org).

Heliograf then went to work identifying data relevant to the story, matching it to the relevant phrases in the templates, merging the two, and publishing different versions of each story for each platform.

The artificial intelligence system also is programmed to alert editorial staff to anomalies in the data, such as tighter races than expected, so writers can jump on the story immediately.

The Post has two goals in mind for its auto- mated reporting: First, to grow its audience. With automated reporting, The Post can cover more niche topics it doesn’t have the staff to cover but which have an audience, albeit smaller than the big-story topics it covers with human writers.

“It’s the Bezos concept of the Everything Store,” Post CIO Shailesh Prakash told Wired. “But growing is where you need a machine to help you, because we can’t have that many humans. We’d go bankrupt.”

The second goal of the Post’s automated reporting is to make The Post more efficient. By turning the drudgery over to machines, Heliograf enables writers to focus on stories that require human intelligence and creativity.

“If we took someone like Dan Balz, who’s been covering politics for the Post for more than 30 years, and had him write a story that a template could write, that would be a crime,” Gilbert told Wired. “It would be a huge waste of his time.”

Gilbert isn’t stopping there. He is working on having Heliograf update data in stories that have already been published. For example, if you were reading a Sunday story on Wednesday and the facts had changed, Heliograf would update the data in real time.

Prakash wants to use robots like Heliograf to scan the internet and social media to see what people are talking about and, if it appears to be a “hot” topic, check The Post’s site and CMS to see if that topic is being covered. If not, it would alert the editors and writers.

The Post is not alone. The Associated Press uses robots to automate earnings coverage, and USA Today uses robots to create short videos.

At the AP, robot reporting has freed up 20% of reporters’ time spent covering corporate earnings and has moved the needle on accuracy, according to Francesco Marconi, AP’s strategy manager and artificial intelligence (AI) co-lead. “In the case of automated financial news coverage by AP, the error rate in the copy decreased even as the volume of the output increased more than tenfold,” he told Digiday.

USA Today uses a tool called Wibbitz, an AI software, to create short videos. The tool takes a text story, condenses it, collects images and/ or video, and even adds narration.

Are you on the fence?

3. Chatbots

The idea of a chatbot as a storytelling tool was inconceivable a few years ago. Heck, chatbots as consumer tools were inconceivable five or so years ago.

But in searching for as many new ways to engage with their consumers as possible, media companies discovered that chatbots were becoming popular methods of communication.

Perhaps the best example of the use of chatbots as a storytelling tool is the Harvard Business Review (HBR). They looked at their audience and found a growing affinity for the communication tool Slack.

Slack bot would be a new way for audiences to engage with HBR content, but there was also the opportunity to reach a new audience through Slack that the publication hadn’t engaged with before.

“Slack was becoming more and more part of workdays around the world,” HBR Senior Editor Maureen Hoch told FIPP.com. “We wanted to first experiment in a controlled environment like Slack, where we knew people were using it at work, that was right in our wheelhouse. That was one of our goals.”

The HBR Slack bot disseminates approximately 200 pieces of ‘Best Practice’ content delivered inside Slack. The Best Practice series focuses on challenges that people face in different work environments, and includes stories like “What to do if you’re smarter than your boss’ and ‘Stop second-guessing your decisions at work”. Hoch said they realised they could take the content and turn it into a database that could be delivered on a bot.

“The thing about these pieces is that they were already written in such a way that there were discrete sections,” Hoch explained. “If you look at a Best Practice article, there was a familiar pattern to each piece, there was a problem, an experts section, a case study, there are do’s and don’ts.

“There are different ways that conversational interfaces are going to be valuable for people, and we wanted to know what kind of response people would have, we wanted to hear from our audience directly, whether this was going to be a useful platform for us,” Hoch told us.

There were a lot of unknowns surrounding the project, Hoch explained. “Would they want to get content from us in this environment? Did they subscribe? Would they stay subscribed? Would they engage? Would we hear from them? What kind of feedback would we get?”

There were a lot of unknowns surrounding the project, Hoch explained. “Would they want to get content from us in this environment? Did they subscribe? Would they stay subscribed? Would they engage? Would we hear from them? What kind of feedback would we get?”

One of the insights Hoch and her team have discovered since the launch of the Slack bot was that it’s fiercely popular among those who’ve engaged with it. “We had about 175-200 pieces of content, and we thought it would take a long time for people to get through that many,” she said. “As early as December, we were seeing people starting to exhaust the content that was available.”

Since the launch of their Slack chatbot, HBR has launched another chatbot on Facebook. They also expanded the offering to include “Whiteboard” shows on hot management and business topics.

In late 2017, the combined bots were doing quite well. “Our bots program now reaches near- ly 20,000 people, most of them daily,” HBR Assistant Director of Communication Amy Poftak told us.

“We’ve done over 100 live whiteboard sessions,” she said. “Our most-watched whiteboard show to date was ‘How to Manage the Work- load of Being a Leader’, which received 177,000 views.”

Until 2013, we were accustomed to scrolling down a page to read a story on our laptops or smartphones.

Then Snapchat introduced Stories.

The “tap to advance” idea took hold — next, Twitter introduced Moments in October 2015, and then Facebook debuted Instagram Stories in August 2016. Media organisations also adopted the “swiping” idea, including Now This with “Tap for News”. The Telegraph and Guardian did the same with their apps.

But there is a difference between swiping between stories and swiping within a story. One is just a content organisation system while the other is an actual storytelling approach, causing the story creators to think about sequence, media choices, style, and rhythm.

“Snapchat forced users to think about sequence in a way that they didn’t have to do before. Considering sequence has some knock-on effects, too. Ordering elements means we also have to think about variety,” wrote Birmingham City University journalism professor and author Paul Bradshaw on the Online Journalism blog.

“In traditional television terms that means aiming to include a variety of shots (close-up, wide shot, and so on), but on a platform like Twitter or Instagram that also means a variety of media: still image, video, gif, text,” Bradshaw wrote.

“You can call this the element of surprise: Repeat the same type of content too often, and the story becomes predictable; there is less narrative tension,” he wrote.

More variety, in contrast, keeps the user engaged.

“So the shift from a vertical, scrolling mode of navigation to an increasingly horizontal, tapping/ swiping mode of navigation adds a new consideration,” Bradshaw wrote. “Those of us who are text-oriented will increasingly need to think not just in terms of how we edit our words, but in how we employ ‘cuts’ between parts of our story, from ‘wide shot’ to ‘close-up’, and so on (literally or figuratively).”

5. Interactive Storytelling

Sometimes words or videos or photos are not enough to tell a story in the most compelling way. Even multimedia stories pairing videos and text might not be enough.

“Interactive storytelling uses technology to captivate the user on multiple levels, engaging as many of the senses as possible, in order to create a unique experience that stands out over traditional forms of content,” wrote Robbie Richards, digital marketing director at US-based software development company Royal Jay, on the marketing company SnapApp’s blog.

“The most sophisticated forms of interactive storytelling utilise a blend of psychology, sociology, cognitive science, linguistics, design, computer science, and artificial intelligence,” Richards wrote.

“If done right, viewers forget they’re reading text, listening to sound effects, looking at visuals and scrolling down all at the same time and begin to experience it as a whole,” wrote Nayomi Chibana, a journalist with visualisation tool creation company Visme, on the company’s blog.

Perhaps the most powerful form of interactive storytelling is the online graphic novel.

Over the last several years, online graphic nov- els have demonstrated the emotional impact of combining multiple media with interactive opportunities to get the reader fully engaged.

Australia’s national public television, SBS or Special Broadcasting Service, created a powerful graphic novel to commemorate the Vietnamese boat people trying to make it to the country in the mid-70s.

The story opens with a picture of a boat in a stormy sea. Clicking to start the story causes the boat to toss, the waves to crash, and the sounds of storm and sea and the hull of the boat to creak. You are sharing the perilous journey with a 16-year-old girl sent away by her parents, a journey that took the lives of as many as 800,000 Vietnamese men, women, and children, according to various estimates.

This is not a dry documentary but a gorgeously illustrated, cleverly assembled, gut-wrenching blend of art, sound, photography, motion, and pacing. The perspective is through the eyes of a scared but strong young lady surrounded by sickness, death, destruction, and soul-sucking pain and stress.

Other media company efforts at interactive stories include:

• “Tell Me Your Secrets” from the BBC

• “Killing Kennedy” from National Geographic (also “Explore the 80s” and “Serengeti Lion”)

• “Seven Deadly Digital Sins” from The Guardian

• “Saving Maggie” by digital comics company Tapas

The “Killing Kennedy” piece is a stunning work of deep archival dives into the parallel lives of John F. Kennedy and his eventual assassin Lee Harvey Oswald. Scrolling up reveals split screens of each man, beginning at childhood and offering at each stage the opportunity to see photos, hear speeches or letters, dive into maps, read historical documents, and then move on to the next stage leading to the climactic shooting in Dallas, Texas. The piece will suck you in for a very long, very enjoyable educational experience.

“The documentary is brilliantly finished and presents a seamless experience which I enjoyed beginning to end,” wrote Judith Aston, Co-Director of the interactive documentary site iDocs.org, on the organisation’s blog. “The dual narrative between Kennedy and Oswald was central to the piece and keeping up with both sides of the story worked for me, with a strong narrative thread running throughout.

“Also I came away from it having genuinely learned something. From not knowing much about the Kennedy assassination beyond the fact he was assassinated, I retained a lot of the information — more than I expected — beyond the experience, thus demonstrating the engaging power of an interactive documentary,” Aston wrote. “Lastly, it’s always encouraging to see large organisations embracing the interactive documentary format and National Geographic seem to be placing it firmly within their repertoire; I particularly enjoyed their exploration into the 80s and the chance to meet lions.”

Less graphically but equally compelling are interactive stories like The Guardian’s “Seven Digital Deadly Sins”.

From the opening, The Guardian tells viewers to “Turn up your sound. Watch. Read. Participate. Share.” The piece combines video interviews interspersed with opportunities for readers to pick and choose their topics, vote on the deadly sins behaviours, and then compare their feelings with other readers. All in a visually stunning setting. (By the way, the Seven Digital Deadly Sins are: Lust, Wrath, Envy, Pride, Gluttony, Greed, and

Sloth.)

6. Live-Streamed Video

Live streaming should be one of your primary story telling tools for no other reason than the fact that live streaming has a huge user base and is rapidly growing in popularity.

Seventy-eight percent of Facebook’s two billion users watch live streaming on the platform, according to Zero Gravity Marketing. Thirty-six percent of internet users said they have watched live video, according to research by eMarketer.

Live stream viewers don’t just pop in for a quick hit: They watch for a stunning 106 minutes every single day on average, according to a survey by New York Magazine and live streaming platform LiveStream.com. According to Tubular Insights, viewers spend 8X longer with live video than on-demand.

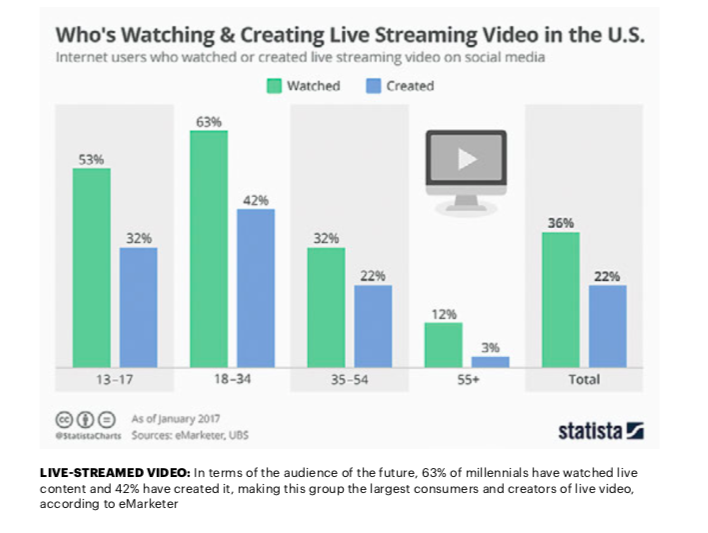

In terms of the audience of the future, 63% of millennials have watched live content and 42% have created it, making this group the largest consumers and creators of live video, according to eMarketer.

Globally, the live stream market will be worth US$70bn by 2021, according to internet market research firm iResearch. China’s live streaming market alone was worth around US$ 3b in 2016, a 180% growth from 2015. At our deadline, it was projected to have grown another 107% in 2017 to roughy US$7bn, according to iResearch.

Audiences also seem to prefer live video: 80% would rather watch live video from a brand than read a blog, and 82% prefer live video from a brand to social posts, according to LiveStream.

One of the biggest challenges is to choose which platform to use for your live streaming. Just because of the size of its user base, Facebook Live is almost a no-brainer. In the US, Facebook Live has surpassed YouTube in terms of live streaming users (17% to 16% of internet users surveyed), according to a study eMarketer and UBS. Snapchat’s Live Stories (12%), Twitter’s Periscope (9%), and Twitter itself (9%) also have footholds in the live streaming universe.

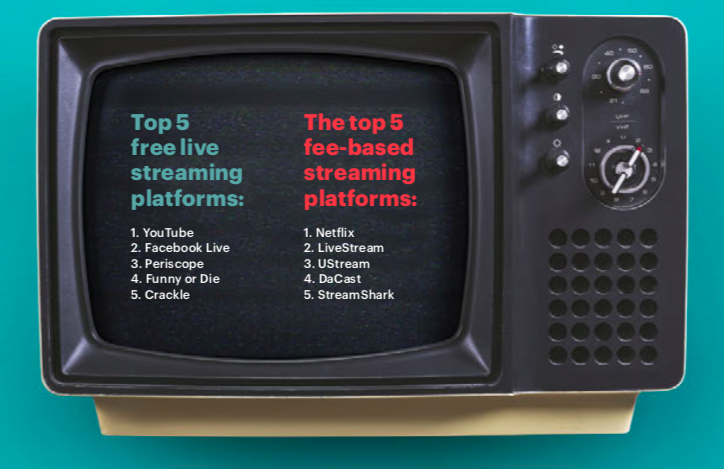

So which of the many tools should you use?

Well, listed on the previous page are ten of the top live streaming platforms, five of which are free, and five that are fee-based, according to Liza Brown, a web editor with software service company Wondershare.

You could spend a lot of time dissecting the pros and cons of each platform, but you’d be better served researching your audience’s behaviour.

“The tool that you use is not important as long as you do some research into what your audience members are using and which platform they prefer,” according to Julia Campbell, author of Storytelling in Digital Age, writing on the blog of digital solutions company Elevation.

“The videos are then stored within the platform for later viewing,” she wrote. “They can also be downloaded and used again, if you so choose, on your website or blog, for example.”

Campbell recommends the following eight ways to use live streaming:

1. Live interviews (viewers can join in, offering their own questions)

2. Live from the field (provide a live, in-the-moment glimpse of the topic/person)

3. Live backstage (people love to get a peak be- hind the curtain before, during or after an event) 4. Live from an event (put your audience at the scene of a big event in your niche)

5. Live Q&A (can be free or an exclusive, paid-for, premium service)

6. Live video series (appointment viewing your audience can count on and schedule)

7. Live “news-jacking” and commentary (comment on news and trending topics in the moment that people are talking about them)

8. Live crowdsourcing (get live feedback on a question or story you’re working on)

7. Multimedia Storytelling

You’re probably thinking, “Oh, come one, who doesn’t know how to do multimedia stories these days?!”

Lots of people.

Too many editorial meetings I’ve attended approach multimedia as text, a video, and some photos. Too many “multimedia stories” exist on a single page on a website with a few embedded photos and videos.

No one gives any deep thought to other media (streaming video, interactive charts and maps and timelines, live events, audio, illustrations, 360-video, etc.), never mind the pacing or rhythm of the story, and the opportunity to interact with the story by swiping to access more or different information on other pages.

Once again, the Harvard Business Review (HBR) is a terrific example of a media company embracing many of the elements of multimedia storytelling.

“The Big Idea” are HBR feature articles re-imagined for digital, according to senior editor Scott Berinato. “We try to help users understand the biggest, most important management issues, presented by leading voices and thinkers,” Berinato told us. “We take on a topic from multiple angles and with multiple storytelling techniques, from video, to interactive, to audio, to events both live and virtual, to good old-fashioned text.

“By releasing it over time, we don’t overwhelm the audience with everything at once, and we can also build the audience over the course of the week,” he said. “They appreciate the daily dose on a topic they want to understand.”

HBR goes beyond new ways of presenting stories to include innovative combinations of other tactics that include an email newsletter and self-diagnostic assessments.

In Brazil, Folha de São Paulo, one of Brazil’s largest newspapers, has been a leader in creating multimedia packages, including the interactive multimedia series “Tudo Sobre” (“All About” in English) in 2013 focusing on the construction of the Belo Monte dam in the Amazon, the Zika outbreak, the 2016 Rio Olympics, the country’s water crisis and deforestation.

“We wanted to provide as much information as possible about an issue, a relevant question on our national agenda. At the same time, we also wanted to apply multimedia and long-form storytelling techniques to go deep and beyond a dossier — it was never supposed to be a mere gathering of information,” Marcelo Leite, a veteran reporter and one of Tudo Sobre’s creators told Storybench.

For example, the package about the Belo Monte Dam in the Amazon unfolded like this: ”The concept was to bring the readers there. Show the people, the construction site, the indigenous, the city, the violence, the environmental issues, the nature, etc. That was the concept and, during editing, the name ‘All About’ came up,” Leite said.

“We do not have a special unit, so we rely on teams drafted from our newsroom: reporters, photographers and videographers, video editors, visual journalists, web designers,” Leite told Storybench. “Sometimes we even hire freelancers if there is not enough manpower available within our ranks. We often hire people from outside for the visual and web development side of these projects.

“The size of the teams between stories varies as well. They can go from 6 to 12 people on the reporting side but, when it is finished, with video editors, narrators, coders, web and graphic designers, the team can tally up to 20 or even more people,” Leite said. “But there will always be a core of three or four people who coordinate each area — reporting, video, infographics and web design — from start to finish.

“It is very hard to pin down, but I can say that, for the first one, on Belo Monte, it took us 10 months to complete everything. But it was the first one. The one on water crisis was finished in about four months, while “Endless Forest” was one of the quickest pieces: we did it in 3 months.

“Generally, we write two or three versions of each chapter. Infographics, photo and video, and web design, all that takes time. We also make a special section for our print edition with four to eight pages, which is also edited during this month-long period.”

Perhaps one of their best multimedia projects covered the coup and military dictatorship crisis in the mid-1960s. You can get lost in it, click- ing and scrolling and listening and watching to end up with a deep understanding of what transpired.

So, will the Golden Age of Journalism be golden for you?

Go research your audience, find out which tools they are using (or which tools you think they’d be inclined to enjoy), train your editorial team in how to use them, and build a discussion of those tools into every story planning meeting.