24 Sep Finally, a business model that makes sense… and money

No surprise: It’s reader revenue, but it’s also a bevy of other sources to make you as close to bullet-proof as other sources to make you as close to bullet-proof as possible

We are past the point of not knowing what to do.

Now, it’s a matter of being smart… or being stupid.

OK, it’s not that simple.

But it’s close: Build reader revenue… and a quiver full of other supporting revenue sources. The last twelve months have demonstrated that readers will pay for unique, high-quality content presented on the platforms and in the media readers prefer.

Some media companies are finally getting more, and in some cases, most of their revenue from the source that makes the most sense: readers. They are the reason we expensively produce all of our content, after all. They should pay for it (more on this later).

But reader revenue can’t carry the load alone. Fortunately, media companies have never had such a diverse selection of other proven revenue stream strategies to choose from.

We have transitioned (slowly and painfully) from a business model that turned out to be extremely vulnerable with just three revenue sources (subscriptions, single-copy sales, and advertising) to business models that can be far more bullet-proof because the diversity of revenue sources would prevent a hit to one of them from sinking the ship.

With all the new revenue streams available to us, the trick now is to choose which revenue strategies work with your unique audiences, and then execute those strategies with teams that understand how to make each one work. The failure to adopt new revenue strategies is often not a matter of desire or will but of knowledge and know-how.

Management teams either don’t know enough about their audiences (a data failure), or about the various revenue options (e.g., “How would we do ecommerce?”), or how to train their people in the new income opportunities.

Similarly, staff often don’t know what to do. They are often afraid to ask questions for fear of appearing stupid or incompetent.

As a result, media executives must do several things: Get audience data, get someone who can analyse and interpret it strategically, investigate revenue options, and then either launch a serious training programme or hire in the talent or both to execute the strategies they’ve chosen.

DIVERSIFICATION

Clearly, the future of a media company revenue strategy is diversification. It’s the new industry buzzword, but it also happens to be spot-on.

Some media companies, like Axel Springer, Immediate, Forbes, G+J, Hubert Burda Media, India Today Group, New York Media, Meredith, SPH and Atlantic Media have already moved past traditional advertising. They have found more diverse and reliable sources of growth, using, among other things, their value as trusted brands, their expertise in their niches, and their creativity to identify new opportunities.

So let’s take a quick look at some of those revenue strategies that media companies are successfully using to build profits. The examples that follow are not in-depth case studies, but rather examples designed to get your own creative juices flowing.

If a media company could get a euro for every time a conference speaker has used the words “reader revenue” lately, they wouldn’t have to worry about a revenue strategy.

After years of committing what has been called media’s “original sin” (offering expensively produced content for free online), media companies have finally come to their senses and are asking readers to pay for what’s scarce and valuable: high-quality, unique, trustworthy, exquisitely produced content that meets readers’ needs like no one else can.

For example, as a trusted filter on world affairs, The Economist “distils the news in a ‘finish-able package’ — an antidote to information overload. “ You can read The Economist to the end but you cannot read to the end of the internet,” Economist Chief Marketing Officer and MD, Global Circulation Michael Brunt told FIPP.com.

The Economist is a premium product that costs three to four times more than other similar publications but readers are happy to pay for it. “We produce quality and our readers find our journalism valuable and are willing to pay for it, We are reassuringly expensive,” Blunt said. “We now charge the same for a digital subscription as for a print subscription on the grounds that you are paying for the content and not the format,” Brunt told FIPP.

The big caveat is that the content has to be worth paying for. If it is, readers will pay. “If you get the content right, there will be a big pay day with consumers.” Condé Nast President and CEO Robert Sauerberg told the annual MPA American Magazine Media Conference earlier this year.

For example, he said, The New Yorker’s subscription revenue has seen a 40% growth year- over-year — a revenue shift that makes the new business model much more than a good theory.

“The value is placing the audience at the top of their strategy,” Ebner Media Chief Innovation Officer Dominik Grau told FIPP. “If you start there and if you observe and listen closely to what the readers, their consumption, content behaviour and interest patterns tell you, then monetising loyalty is simply the next step in finding the relevant models to what you’ve seen.”

CEO of Time Inc. UK Marcus Rich agrees. In fact, he says, what has been at the base of expanding their business has been a deep under- standing of their subscribers and their passions. “Time Inc. UK has built its business on audience passion,” Rich told FIPP. “The Time Inc. titles serve customers who are incredibly passionate about subjects beyond work, whether this be cycling or sailing.”

Digital pure plays like the San Francis- co-based The Information link a large part of its subscription model to exclusive events. The RSVP tab to attend an exclusive “Young Professionals Launch Party (for under 30s) at the private home of a well-known tech entrepreneur” actually takes a reader to a page to subscribe to The Information’s Young Professionals Plan at $199/year for the next five years.

Subscribers then gain access to that event as well as to conference calls, in-depth articles, a members-only Facebook group, The Information Videos, and more exclusive events.

More and more media companies are making the move to drive reader revenue, not only to build a better business model but also to reduce their reliance on the platforms, according to a report from Axel Springer.

Axel Springer, in surveying publishers in Germany, France, Spain and Scandinavia, found executives upbeat about the future of subscription models. Nearly three-quarters (70%) told Axel Springer they have evidence that readers’ willingness to pay for content has increased over the last twelve months, according to the report.

“Unlike ad revenue, where the big platforms like Facebook and Google take such a large proportion, digital readership revenues and the relationships we can develop with readers provide another revenue stream that helps us reduce dependency on platforms,” Bild Digital MD Stefan Betzold told Digiday.

Fifty percent of adults in developed countries will have at least two online-only media subscriptions by the end of 2018, according to a Deloitte study. By the end of 2020, Deloitte predicts that number will double to four subscriptions.

The subscription trend affects more than the big boys. “Niche subscription-based publishers like Sinocism (Bill Bishop’s daily China news- letter), The Second Arrangement (Kelly Dwyer on the NBA), and The Hustle (daily tech and business news) are also betting on the value of specific, high-quality content,” Jeanne DeWitt, director of North American sales at tech com- pany Stripe, wrote in MediaShift earlier this year. “The Hustle, in particular, has already seen impressive traction. With more than 500k sub scribers and a 40% open rate — nearly twice the industry average. It plans to expand its services in 2018.”

Paywalls seem to be working because people who really care about the content can’t stand not to be able to get it. “It is my strong sense that paywalls are an essential part of the future of journalism,” Wired Editor-in-Chief Nick Thompson, who joined Wired last January after seven years as Editor of NewYorker.com, told journalism think tank Nieman Lab. “We don’t know exactly how the web will develop, which platforms will become big, but we do know that having a direct monetary relationship with your readers is one way to insure that you have a stable financial future.”

Reader revenue is also attractive because it “creates the incentives to do the best possible journalism,” Thompson said. Rather than write and optimise for whatever will travel best on Facebook or attract the most attention, Thompson said that subscription revenue puts the business incentives and editorial incentives on the same axis, which is fundamentally good for readers. “That’s just a great place to be,” he said.

The business of finding those readers most likely to subscribe may be turning into a science. Scandinavian media giant Schibsted is using reader behaviour data to predict which types of readers are most likely to respond positively to a subscription offer.

The model, developed by the Schibsted data science team, was launched in early 2017, and has successfully identified types of readers who, it turns out, are three to five times more likely than the average reader to buy a subscription, Data Science Team Member Ciarán Cody-Kenny told Nieman Lab.

Once identified, the sales staff can, for example, target these specific registered users on Facebook with bespoke subscription offers.

Targeting such readers on Facebook has resulted in a 22% increase in successful subscription pitches, according to the company. Similarly, the marketing team spent 35% less advertising on Facebook because they knew whom to target.

The data team was also able to increase the efficiency and success rates of the telemarketers. Prior to employing the reader behaviour data, Schibsted’s telemarketers were shooting in the dark and, as a result, they had a success rate of just 1%. After employing the reader data, the success rate shot up to 6%, according to the company.

The data team was also able to increase the efficiency and success rates of the telemarketers. Prior to employing the reader behaviour data, Schibsted’s telemarketers were shooting in the dark and, as a result, they had a success rate of just 1%. After employing the reader data, the success rate shot up to 6%, according to the company.

You might be thinking about picking up the phone to try to license the Schibsted system. But, unlike the Washington Post which licenses its built-in-house Arc Publishing System, Schibsted has no immediate plans to license theirs. I wouldn’t bank on that being the case for long…

The bottom line for reader revenue? It is working for companies that offer the right content to the right audience on the right platform at the right time. And the audiences of the future — the millennials — are past the whole “information must be free” thing.

“The beauty of millennials is that they are very comfortable buying anything online and using their credit or debit card,” Meredith Executive Chairman Steve Lacy told the Wall Street Journal. “Our interface with them is the credit card and auto renewal. It has to be the right content, and it has to be served to them the way they want it. But they’ll pay for it”.

Another form of “advice revenue” is to start taking financial advantage of something many of you have been doing all along anyway: Recommending relevant products and services to your readers.

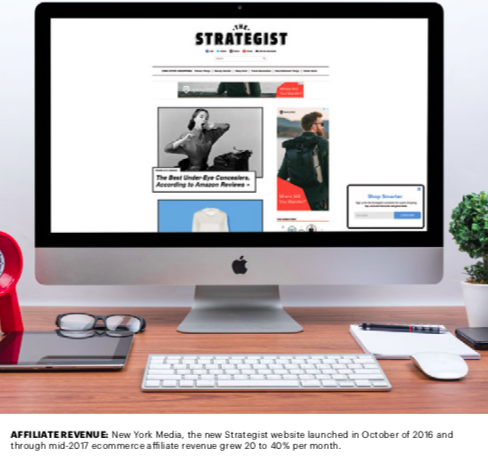

At New York Media, a review of their decades-old recommendation services through a profit lens revealed a revenue opportunity. When Director of Business Development Camilla Cho looked at the expert recommendations, she saw very healthy engagement rates. Readers seemed to love and trust the advice of New York editors. Cho wondered if that could be monetised.

She did a test with affiliate links on ecommerce articles created by her biz dev team to find out if readers would read, click and buy. “After a period of five months, we blew through the KPIs,” Cho told Folio. “We were able to prove a real viable business here.”

So New York took its iconic section — The Strategist — which has been doing editor recommendations for decades, and turned it into a website to do that and run affiliate links for some of the products recommended.

The Strategist editorial team only runs recommendations of products “the editors or writers stand behind,” Cho said. The new Strategist site launched in October of 2016 and through mid-2017 ecommerce affiliate revenue grew 20 to 40% per month, partially due to the low level initially, according to Cho. The site also encouraged related revenue ventures such as a Strategist pop-up shop at the magazine’s 2017 Vulture Festival.

If you’ve figured things out, why not make money on that hard-earned expertise?

The aforementioned Washington Post Arc publishing system, which it went to great expense to build, now represents a significant annual revenue source. While the Post doesn’t disclose revenue figures, Arc executives have been quoted saying their revenue doubled from 2016 to 2017, and they expect it to double again this year. The company sees the platform as something that could eventually become a $100 million business, Post CIO Shailesh Prakash told Fast Company (are you listening, Schibsted?).

At Atlantic Media, they have transformed themselves, going from relying on print for 80% of their sales to the point where today print accounts for only 15% of the company’s revenue.

The company learned a lot of tough lessons in making that transition and so they thought: Why not capitalise on that knowledge? They also wanted to protect their ad-building business, concerned that their clients might take native advertising in-house.

“We were concerned for the long-term viability of the digital native ad market,” Michael Finnegan, president of Atlantic Media, told Folio:. So he thought, “why don’t we build the disruption ourselves?” Cue Atlantic Media Strategies (AMS), which audits advertisers’ digital efforts, develops and executes content-focused campaigns, and sup- ports ongoing digital projects for clients.

Today, AMS is the fastest growing division within Atlantic Media. AMS revenue went up 29% in 2016 and, at press time, appeared to be growing another 32% in 2017, according to the company. Staff has doubled to 40 since 2014.

Two of the advantages the duopoly have in the battle for ad dollars are data and cross-channel access.

But media companies are fighting back, working hard to gather more data and cross-channel access, while also resurrecting a magazine’s key differentiator: our relationship with our readers.

It starts with data acquisition, “Access to first- or second-party data and deeper measurement will continue to be at the forefront of planning at all layers of the funnel, which is where Google, Facebook and Amazon continue to evolve and either invest in technology or break down walls to enable such opportunities,” Kara Scagnelli, VP/Group Director at the DigitasLBi agency, told Folio: magazine.

But to maximise reach, media companies generally don’t want to put data-gathering road- blocks like registration and log-ins in the path of readers going to their stories. But they need data. The solutions to universal reader identification are complex and require that media companies partner with other services and use new technologies.

“We utilise a DMP [Data Management Platform] to identify users across channels and then push those audiences into ad serving platforms inside and outside our network,” Mark Crone, Bonnier’s Senior Director of Email and Database Marketing, told Folio:. “We also track some users manually and with external partners. In Q1 [2018], we will begin utilising an additional platform giving us a more complete view of each customer, and we will be configured to facilitate the identification and activation on a more automated basis.”

Meredith uses more than registrations and log-ins to capture and track reader IDs. Email and newsletters are Meredith’s biggest source for email addresses as the key for identifying reader activity across content, but not the only way.

Recipe collections, shopping lists, and the Meredith’s Baby Names app are also strong drivers of ID collection, as are the registrations for such things as fitness challenges and contests, Meredith EVP, Chief Data & Insight Officer Alysia Borsa told Folio:.

But media companies bring a special kind of data to the table that the duopoly and other platforms cannot. “Legacy publishers actually have a foot up simply because we have had and continue to develop a known relationship with our consumers, called subscriptions,” Judith Hammerman, Time Inc. (now Meredith Corporation) SVP of Data Commercialisation, told Folio:. “I can tell [an advertiser] the kind of offers the recipient has responded to and use that terrestrial address and start to tie it in with what has been an unknown consumer online. We can capture that and store it into one consumer record.

“The value is in the robustness of the profiles we bring,” adds Borsa. “It is not about the platform, but the consumer.”

Borsa cited cross-channel identification as key to frequency capping and sequencing/timing of advertising messages to the same user. She said advertisers are increasingly demanding that the web be tied to mobile and mobile to shopper marketing via an app. For example, Meredith’s extremely popular Allrecipes.com site and app bring web, mobile, and in-store connections together. The app can identify a user’s location to ping them with real-time alerts to sales when they are actually in the store.

We can’t do all this data and cross-channel stuff ourselves, Borsa said. “The reality is we are going to need to partner and work with vendors to supplement our identity solutions,” she told Folio:. “Meredith is looking at consortiums like the DigiTrust initiative and OpenID, among others, that standardise logins and universal identification across publishers.”

“The opportunity for us is that bigger more strategic deal, as opposed to many little transactional campaigns,” Borsa said. “We have been very successful in building out strategic partnerships of sharing data and insight up front to help them set roadmaps and strategies.”

What can you say about digital ads?

They drive people to install ad blockers? They have abysmal click-through rates? Their CPMs are not sustainable?

And now, digital ads that don’t conform to the ads.txt standards will be blocked by Google’s Chrome browser.

Starting 15 February 2018, Google integrated an ad-blocker into its Chrome browser to cut down on spammy or intrusive advertisements. Not all ads, but those that are considered bad according to standards determined by the Co- alition for Better Ads, which bans things like full page ads, ads with autoplaying sound and video, and flashing ads.

Prior to the launch, Google created an Ad Experience Report to help publishers see if their sites would fail its forthcoming standards. Companies were given time to fix the offending ads and resubmit them for approval.

Some publishers reported getting warning labels on ads they subsequently fixed but they claimed that the warning label wasn’t removed for months. A Google spokesman told Digiday that warning labels were not automatically removed; the publisher has to request a review, after which, the warning is removed within days, the spokesman said.

![]()

Wired magazine has a number for you: 300%. That’s the increase in October 2017 ecommerce revenue year over year.

The growth appears to be a direct result of a serious investment in the commerce-focused editorial teams. “We basically quadrupled our output,” Wired Site Director Jason Tanz told Digiday. “We were leaving money on the table.”

Wired brought on three new editorial staffers to boost their reviews team to seven and launched a newsletter and content licensing strategy to increase the distribution of their reviews content.

Tanz said products to be reviewed are not determined by search results from platforms like Google and Amazon but by editorial staff acting independently. “We’d never not review something because we felt we couldn’t monetise it,” he said.

The Wired design team also changed the review pages to add “Buy” buttons at the beginning and end of every story. The new design as well as a new stamp of approval (“Wired Recommends”) which Tanz said will eventually give Wired the chance to build out a content licensing revenue stream to brands.

Events must be an important part of a future-proof audience revenue strategy, BBC Worldwide Publishing Director Chris Kerwin told FIPP.com.

Kerwin uses BBC Good Food as an example of a brand which uses increased audience engagement to grow well beyond digital advertising revenues. BBC Good Food was born from a willingness and ability to experiment with different live concepts. “Our live business is an important part of the publishing mix, with over 300,000 people attending a Good Food event in the UK each year,” Kerwin said.

At digital pure plays like the aforementioned San Francisco-based The Information, subscriptions are tied to exclusive events. The RSVP tab for The Innovation’s invitation to their Young Professionals Launch Party required a subscription.

Forbes’ events business has been growing very aggressively, according to Forbes Media Chief Revenue Officer Mark Howard speaking to FIPP. “The 30 Under 30 [event] franchise has been a real strong point for us over the last several years.”

“It launched in the States seven years ago, this is our third year in Europe, and we’re also in our third year in Asia, so we’ve been able to identify those individuals who are under the age of thirty who really do set out to change the world from a number of different categories,” Howard said. “It ranges from social entrepreneurship to investment, banking, technology, media, and advertising.”

“We’re going to be doing a European Summit in Amsterdam in September [2018], we do a global summit in Tel Aviv in May, we do a US event in Boston in October, and an event over the summer in June or July in Asia,” Howard told FIPP. “We are making our events a cornerstone of what we do and we’re working more and more with our partners to add that live touchpoint component to a lot of the bigger types of pack- ages that we take to market, so it’s all been part of a bigger growth strategy.”

More than a quarter of publishers believe events are the revenue source that will increase the most in the next two years, increasing to 42% for business-focused publishers, according to a HubSpot 2017 report.

Hearst Live, Hearst’s events division, doubled its revenues, profits and number of events last year, according to the company.

Revenue from events accounts for about 10% of Shortlist Media’s revenue, double 2016, according to the company. Shortlist expects that figure to double next year to nearly 20%, according to the company.

But this optimism obscures the challenges in growing an events business.

Despite glowing anecdotes, events are not easy money.

“Events are not the golden goose publishers think they are,” Jon O’Donnell, Managing Director of ESI Commercial, which publishes the Evening Standard and The Independent, told Digiday. “Events work when they fit into the publisher’s key interest areas, passion points and depth of knowledge.”

“They say events are like a sausage, wonderful to eat, but you don’t want to get involved in what goes into them,” Ruth Carter, Telegraph Managing Director of Events who has 20 years of events experience, told Digiday.

Running a profitable events business often means hiring a team of events experts and even dedicated salespeople who understand selling sponsorship packages.

While some publishers claim events make up 20% of their revenue, there are fixed, upfront costs such as venue rental, speaker fees, multi- media and branding costs, and marketing. A failure to drive enough ticket sales has serious financial consequences.

Memberships may not be for everyone, but for some media companies, they can be very lucrative.

The Guardian is the poster child for memberships lately. Eschewing tchotchkes like tote bags, event tickets, and other schwag to attract membership fees, the Guardian appealed to its readers’ hearts.

“Our appeal is very much an appeal from The Guardian,” Amanda Michel, Deputy Executive Editor of Membership, told the Nieman Lab. “It doesn’t speak to the section they’re in. It doesn’t speak to what they read. It speaks to the heart of the Guardian’s moment.”

“Our marketing colleagues… are used to using one-line [pitches] to advertise membership,” with a focus on pithiness and wit, Membership Executive Editor Natalie Hanman told Nieman Lab. “The longer appeal resonates with people more. We need to explain to people why we are pursuing this approach. Even as journalists used to writing snappy headlines, we need to take a bit more time here.”

“We’ve moved away from the traditional transactional model to a more emotional one that’s rooted in our journalism,” she added.

It has worked. Big time.

As recently as 2016, the Guardian had only 12,000 members. Today, they have 300,000. The Guardian also chose not to institute a paywall. Instead of preventing people from accessing Guardian content, their membership model makes more content available to members.

“Will it be a wall between the reader and the content? No, it won’t be. It’ll be adding more value for people who want to get more involved in the Guardian, who feel passionate about the Guardian,” former Guardian Media Group CEO Andrew Miller told Nieman Lab to explain the mindset at the time.

“We recognise we have to get more direct-to-consumer revenue over time, and the way we will do that is through membership-type propositions, but it’s going to be much more than a paywall,” he said. “A paywall is to me an inverse loyalty scheme, where the more you consume the more you pay, which doesn’t seem to work.”

“It was in April last year that Amanda and I did the first experiment basically using a carrot, not a stick, to support the Guardian’s journal- ism,” Hanman told Nieman Lab, explaining that the Panama Papers investigation was the first test of some of those ideas. “We were really drawing the link between the time and effort and skill we put into that investigation, working with these organisations around the world and asking people: If you value this, please contribute toward this.”

By the end of 2017, EIC Katharine Viner was able to announce that reader financial support officially surpassed ad revenue. Viner announced that 500,000 individuals contributed monthly to the Guardian as members and print/digital subscribers, and another 300,000 one-time donations have contributed to the ascension of reader revenue over ad revenue

“‘Subscription’ sounds transactional, ‘membership’ sounds like a two-way relationship that gives you access to things you can’t get elsewhere,” Gannett CMO Andy Yost told Publishers Daily. “We need to really lead with why our brand has what you need from a benefits perspective, and that’s a way to help us more effectively convert our audience to a paid subscriber,” Yost said.

So at Gannett, the largest newspaper group in the USA as measured by circulation, they offer memberships to give readers what they want.

Yost said media can succeed by feeding consumers’ “appetite” for experiences that meet their needs.

Some readers might want a premium product that delivers every possible sports story while others would pay for an ad-free experience.

But Yost cautions that you can’t get readers to pay for memberships unless you can demonstrate the value of their investment. Tailored content does exactly that, he said.

Gannett also offers an Insider Loyalty Program which delivers deals and premium content to members, plus offers from retail partners or preferential access to special editorial event series.

Gannett started offering an ad-free mobile membership in late 2017 (US$2.99 a month to access USA Today ad-free in its mobile app).

![]()

Newsletters fell out of favour for a while. Publishers were too busy chasing the scale that seemed to come instantly with search and social media compared to the slow, laborious process of building newsletters (never mind that newsletters offer more loyal, more trackable audiences).

Then there is the measurement problem. It began in 2013 when Google started caching third-party images embedded in emails. As a result, neither advertisers nor publishers could prove the number of ad impressions, a problem which, for many publishers, continues today.

“You can proxy it with email open rates, but that’s not perfect,” Chris Shuptrine, the Marketing Director for Adzerk, a native ad suite used by publishers and communities including Thrillist, Reddit and Imgur, told Digiday.

“What publishers are doing now is merely scratching the surface,” Dave Helmreich, COO of LiveIntent, told Digiday. “Email is no longer about sending email. It’s about the access it provides to identity and marketing to people in a mobile-first world.”

Solutions in vogue now include offering sponsorships instead of display ads.

At Axios, founders Jim VandeHei and Roy Schwartz are tweaking what worked for them at Politico: Axios newsletter sponsorships are being sold as one-week exclusives. Knowing they have the newsletter to themselves allows advertisers to build different creative tacks or tell stories.

The approach also allows Axios to maximise their revenue when there are weeks of high-interest news. The team sells sponsorships at premium prices when they know readership will be high.

Native advertising has been growing elsewhere, why not with newsletters? Media companies like Hearst, Refinery29, and BuzzFeed have long used native ads in their newsletters. But with the increasing uniformity of newsletter design plus the growing ease of placing programmatic ads in newsletters via exchanges, native advertising should become a much bigger contributor to newsletters’ bottom line.

A third solution is to embed affiliate links in newsletters. Again, this is not new (Refinery29 and BuzzFeed have been doing it), but it does represent another increasingly easy source of both revenue and user data.

Many magazines have done product licensing in the past, but it was never a significant contributor to the bottom line.

Things are different these days.

And, as with so many initiatives today, it can all start with data.

For example, at Hearst UK’s Men’s Health title, research and an examination of reader behaviour data revealed that 70% of its readers are the household’s primary food buyers. As a result, it wasn’t a huge gamble to launch a line of Men’s Health-branded food products targeted at their audience.

The Hearst UK titles together have at least 25 different licensed product arrangements today, including the Men’s Health food line as well as flower bouquets designed by Country Living, gym equipment from Men’s Health, and a carpet line from House Beautiful.

While Hearst UK’s product licensing today constitutes only 5% of total revenue, that nonetheless represents a 30% increase from 2014, and Hearst expects that percentage of revenue to grow to 15-20% of total revenue by 2020, according to Hearst.

“Licensing is supposed to do two things: sell products and give the manufacturer a long- term strategic association with our brand

— that’s gold dust,” Hearst Magazines UK Chief Brand Officer Duncan Chater told Digiday.

Hearst’s product licensing deals take around a year to finalise because they need to work out the product, packaging, launch and marketing plan, Chater said. The long timeline is necessary because of the amount of involvement Hearst’s brands invest in each product. For instance, Chater said the Men’s Health editorial team spent a great deal of time making sure its brand of beef jerky had the right protein levels without compromising on the taste.

The investment of time in each deal might slow the campaign’s speed to market, but the payoff is a long-term relationship. For example. Hearst’s relationship with sofa retailer DFS has lasted seven years. And the benefits go both ways. At DFS, the exclusive Hearst brand partnerships with House Beautiful, Country Living and French Connection have resulted in a 35% growth in bookings in 2016, an increase of 75% from 2015, according to the retailer’s annual report.

The former Time Inc. titles, now owned by Meredith, had a history of product licensing but starting in 2016, they ratcheted up product licensing and saw it grow as a revenue contributor.

One of their titles, Southern Living, struck a deal with a big US department store chain (Dil- lards) to create an exclusive, expansive line of home goods ranging from furniture and kitchen- ware to rugs and bedspreads. Since the launch, the Southern Living line has become one of Dillard’s top-selling lines, according to the company. From an initially modest offering, Southern Living now offers more than 100 selections.

In addition to being a revenue growth sector, product licensing is an invaluable source of new data media companies can get from its audiences and purchasers — data which can be leveraged in developing content and commerce strategies.

![]()

Media companies globally continue to embrace programmatic advertising. And why not? Handled correctly, programmatic provides a reliable, easily scalable, data-driven, revenue stream.

And it’s getting increasingly easy to sell on an automated basis — which means that platforms like native advertising and newsletters that were difficult to sell programmatically are now available.

Two factors have contributed to this: The rise of programmatic exchanges combined with relative uniformity in newsletter design. Native ads are thus able to be a significant contributor to newsletter profitability.

Today, two-thirds of Forbes’ digital ad revenue comes from programmatic, direct deals and branded content, with revenues from print, live events and custom research making up the remaining third, Chief Revenue Officer Mark Howard told Digiday.

And once again, data is part of the answer.

At the Guardian, they use open market data to pinpoint high-value buyers and redirect them to Guardian premium programmatic — a tactic the Guardian claims has increased yields for the publisher and the assurance for the advertiser that their marketing money is going to working media.

The New York Times is also building its programmatic operations by allowing the sale of their custom ad units through programmatic.

In the third quarter of 2017, the Times started offering its custom Flex Frame units programmatically. As a result, in that single quarter, the Times doubled its programmatic direct revenue over the previous quarter, Times Director of Programmatic Advertising Sara Badler told Digiday.

As part of the programmatic push, the Times doubled its programmatic staff to six, expanded programmatic sales globally, and opened all its ad products, including home page and video ads, to programmatic buyers, according to Badler.

“Clients want to do cooler things programmatically,” said Badler. “It’s not just about banner ads anymore.”

Open exchanges still account for more than half of the Times’ annual programmatic ad revenue, but the percentage is shrinking as the Times’ programmatic direct business grows, said Badler. But the Times still keeps its video ads and custom units out of the open exchanges, due to lower rates and far less control over what brands end up on their site.

Chris Wexler, Executive Director of Media and Analytics at ad agency Cramer-Krasselt, said the Times selling custom units programmatically is indicative of a broader shift in the industry. Wexler said programmatic is finally beginning to shift from “just a way to clear remnant banner inventory to a core mechanism that will power the future of most media transactions,” Wexler told Digiday.

Some statistics about video revenue might make you think that a pivot to video was indeed in order.

But a closer examination of the data reveals otherwise.

Video continues to drive monetisation for media companies, according to a 2018 report by the publisher trade group Digital Content Next. According to the report, 85% of all media third-party revenue came from video.

That sounds pretty good, right?

But the devil is in the details.

One of the devils is that most of that video revenue went to media companies that are established video producers, especially TV/cable companies which gained through over-the-top (OTT) and syndication partners like YouTube.

The other devil: Video content is much more expensive to produce, making the video dollars less impressive when you think about the ROI.

That said, there are more ways to skin the video revenue cat.

In mid-2016, Motor Trend created an on-demand streaming video service that cost US$5.99 a month or US$99 a year through Roku and Apple TV. Subscribers get access to more than 2,000 hours of content and more than 800 hours of live streaming of motorsports racing events.

In just over a year, Motor Trend has attracted more than 100,000 subscribers.

Now, in a partnership with Discovery Communications, the Motor Trend video library will be combined with Velocity, the Discovery owned cable channel, with an eye to using the Motor Trend template for other Discovery brands such as Discovery Science.

Motor Trend uses Facebook to promote its show with teasers and short clips. And they are partnering with Facebook to create original content for Facebook Watch.

According to the company, while Motor Trend OnDemand is responsible for only a small percentage of corporate revenues today, the company anticipates on-demand video will soon contribute 20% of total revenue.

In addition to streaming video subscriptions, another way to make expensive video more profitable is to eliminate ad tech vendors.

In France, Le Figaro and Le Monde formed a joint sales alliance called Skyline in the fall of 2017 and, in the process, eliminated 12 ad tech vendors from their digital trading supply chain.

In a stunning turn of events in a stunningly short period of time (several months), Le Figaro’s video ad revenue skyrocketed 50%, according to the company. Le Monde did not reveal its results, but experts estimated their results to be similar to Le Figaro’s.

“Since we started Skyline, every time we have cut an ad tech vendor, we have made much more money,” Le Figaro CEO Alexis Marcombe told Digiday.

At this point, advertisers can only purchase ads on the Le Figaro and Le Monde sites through the partnership. As of late 2017, 125 campaigns representing 50 brands, including Carrefour, Volkswagen, Qualcomm and Citroën (all of which have booked repeatedly), have run on the sites, Marcombe said.

While Marcombe would not disclose revenue totals, industry sources told Digiday it was around €1.5 million (US$1.9 million), which they expected to rise to between €2.5 million (US$3.1 million) and €3 million (US$3.7 mil- lion) by mid-2018.

The partnership was formed as an offensive move against Facebook and Google. Eliminating the vendors was just one of the steps the partnership took to regain control of their ad inventory. By bringing control in-house, the partners could recoup the revenue that the tech vendors had taken for years. The alliance’s core partners are now AppNexus and Google.

One of the partners, Le Figaro, also has several other vendors, including the Rubicon Project because Le Figaro is part of the French premium publisher marketplace called La Place. This solution might sound too good to be true, and for some smaller media companies, it might be.

Eliminating vendors involves a short-term revenue loss, and that is a major deterrent for companies without the resources of Skyline, Marcombe said.

“It was a relatively seamless transition because we have the engineering capability, and we could bear the expense,” he said. “But the money returned to us was pretty instantaneous.”

It was not just a matter of discontinuing the vendors. Skyline had to be able to offer the same ad formats the vendors had and that required building new ad products in-house, not something every media company can do. Skyline had the benefit of technical support from their partner, AppNexus.

But, if you can do that, Marcombe says there might not be any short-term revenue loss. “If you can ensure your own ad stack offers the same level of quality as what’s available from vendors, then you can get your money back quite quickly,” he said. “We prefer to get back [control of] our inventory and offer full transparency on what advertisers are buying to ensure they’re getting the real value of our inventory.”

Voice-activated devices have captured consumer attention in numbers no one saw coming.

Globally, 24 million smart speakers were shipped in 2017, a 300% growth over 2016 shipments of six million units, according to business planning firm Strategy Analytics.

In just the last six months of 2017, voice-activated devices sold in the US doubled in number, according to Consumer Intelligence Research Partners.

Devices weren’t the only thing doubling.

News site CNBC said its voice audience on Amazon and Google Home doubled in 2017. That was not the only good news for CNBC. The company discovered that voice audiences are the second-most loyal audiences after those on its mobile app.

The success of companies like CNBC has prompted others to jump in.

In February 2018, Condé Nast titles Vogue and GQ began creating content for the Amazon Echo Look, a device that includes a camera. When users take a selfie and send it to one of the titles, they will be offered fashion, celebrity or service content, some of which will be shoppable.

Making content shoppable begins to answer one of the conundrums of voice devices: How to monetise them. In this case, if a user clicks to buy a product from the publisher’s content via the app, the publisher gets a commission.

Amazon is not paying Vogue or GQ for the posts, but Condé Nast rolled the dice based on reader data that showed their audience was looking for help in selecting things to buy.