30 Oct How micropayments can deliver new revenue, new readers & new insight

Blendle has proven that young people really will pay for content, and they really will read it on their smartphones, but only quality content, and only if they can get their money back if they don’t like what you sold them.

How many prophets have we heard crying in the desert: “I have the solution to the media’s problems!”? Too many to count.

Some of us even purchased their wares and have closets full of gadgets or software discs that didn’t quite pan out as planned.

The Dutch micropayment company, Blendle, was seen as one of those slightly whacky prophets when they launched in 2013.

And with good reason.

Micropayment missteps and failures date back to the early 1990s when companies like FirstVirtual, Cybercoin, Millicent, Digicash, Internet Dollar, Pay2See and others rose and collapsed. A little later, companies like Beenz, BitPass, and Peppercoin appeared and disappeared.

“Guess how many times it [a micropayment system] has been successfully tried in the past 17 years?” asked Ink, Bits and Pixels editor and owner Nate Hoffelder in a 2015 post on his company’s The Digital Reader blog. “If you guessed zero, you would be correct.”

OK. Point taken.

But does early failure predict ultimate failure?

While micropayment systems don’t rise to the level of historical impact as the automobile, would anyone care to guess how many automobile companies failed in the formative years of that industry (1890-1915)?

Three hundred and eighty-one. In the United States alone. You can look it up.

What is puzzling about the critics of micropayment systems is their persistent pessimism, even in the face of proven success. When Hoffelder wrote his piece in June 2015, he was predicting the demise of an already successful micropayment operation in the Netherlands called Blendle. And Hoffelder was not alone in his doubt. Critics abounded.

And yet…

As we speak, hundreds of thousands of Dutch and German readers are using micro- payments to purchase individual newspaper and magazine stories, and more do so every day (an estimated 5,000 new micropayment users a month).

After a five-month trial phase, Blendle officially launched in October 2014 with just 130,000 users in the Netherlands. Today it boasts 550,000 users in the Netherlands and in Germany (launched in September 2015 with 100 publishers on board).

Later in 2016, Blendle has announced it will launch a version in the United States.

For the Dutch publishers, the Blendle revenue already amounts to more revenue than Apple is delivering.

“We’re proving that people do want to pay for great journalism,” wrote Blendle founder Alexander Klöpping in a one-year anniversary piece before the company’s launch in Germany.“The goal: put all newspapers and magazines in the country [the Netherlands] behind one (quite sexy) paywall, and make it so easy to use that young people start paying for journalism again.”

Those same young people, and many other consumers as well, are being acclimatised to paying with so-called “digital wallets”.

Those “wallets” are either electronic devices or web-based programs enabling consumers to make purchases digitally, without having to pull out a credit or debit card or cash. Consumers can use their smartphones where payment information is stored, or access programs such as Apple Pay, Google Wallet, Samsung Pay, or PayPal.

It is not uncommon to be in line at a coffee shop or department store and see customers use their smartphones to complete their purchase. Apple Pay is available on iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, Apple Watch, and some iPads. It uses Near Field Communication (NFC) technology and can be used at any business that has contactless terminals.

Google Wallet is a multi-platform digital wallet that is compatible with MasterCard Pay- Pass and Visa’s PayWave systems and works with many different smartphone brands. Samsung Pay is also a device-based wallet compatible with the Samsung Galaxy S6 and later models. Unlike Google Wallet and Apple Pay, Samsung Pay uses both NFC and Magnetic Secure Transcript (MST) technologies, making it compatible with both contactless pay terminals or traditional magnetic strip terminals.

Apps also enable digital payment. Starbucks, for example, offers customers the ability to pay for their java with their phones using the Starbucks app. Apple enables payments within apps for some of the biggest names in retailing: BestBuy, Dunkin Donuts, Etsy, Kickstarter, Uber, Target, TicketMaster, and more. Payment app Venmo is very popular with young people because it enables them to reimburse a friend for a cash loan but also to pay for purchases.

Several micropayment companies are targeting the media industry, including US-based iMoneza and Tipsy, and UK-based 1-Pass. Apps also enable digital payment. Starbucks, for example, offers customers the ability to pay for their java with their phones using the Starbucks app.

iMoneza is a cloud-based solution designed to enable publishers to charge for single stories for a very small fee (usually US $0.10 – US $0.50 to read premium content.

“Publishers can keep their web traffic high by offering basic content for free, but they can increase revenue by pricing 15-40% of premium content individually,” said Mike Gehl, president and chief executive officer.

The iMoneza solution “pays for itself,” ac- cording to Gehl, as iMoneza only gets paid when the publisher generates revenue (iMoneza earns a small percentage). “There is no up-front cost, no monthly fee, or any other cost whatsoever,” said Gehl. “This ensures the publisher will realise a positive return on investment.”

Tipsy, by contrast, appeals to readers’ altruism to support the sites they frequent. Tipsy “goes along with people’s willingness to contribute, but removes all the obstacles that would get in their way of doing so,” Tipsy creator MIT professor David Karger told journalism.uk.

Tipsy, by contrast, appeals to readers’ altruism to support the sites they frequent. Tipsy “goes along with people’s willingness to contribute, but removes all the obstacles that would get in their way of doing so,” Tipsy creator MIT professor David Karger told journalism.uk.

“The need to click a button every time you want to pay somebody is, to me, a pretty significant obstacle,” Karger said. “Tipsy asks readers to decide in advance how much money they want to con- tribute or “donate” and “does the watching and the calculating for you.”

Readers can donate from US$5 to US$100 or more a month, and adjust their monthly donation at any time. At present, Tipsy is free to publishers, and the organisation does not take a cut of the donations. As of March 2016, Tipsy had two publishers on board: ProPublica and Global Voices.

1Pass is a London-based single-article sales start-up that went live in 2016 after testing its platform through 2015.The 1Pass model differs fundamentally from that of Blendle. Both do single-article sales. But 1Pass seeks exclusively to help publishers sell single articles from publishers’ own websites. 1Pass works in the background, running pre- paid accounts for readers, and supplying publishers with plug-ins that can be dropped instantly into any WordPress, Drupal or Craft website.

1Pass developed its platform throughout 2015 using hundreds of articles sourced from the Financial Times, The Economist, Foreign Affairs and other quality publications, which it promoted for sale using social media.

By the end of 2015 it had acquired some 15,000 customers, and accumulated some impressive analytics about what happens when real people use real money to buy real content.

A few insights:

- There is very little price discrimination be- tween US$.25 and $US.99 per article

- The most important predictor of an article’s sales is not the topic, nor the publication, but the author

- Readers are surprisingly unconcerned by length; an 800-word article sells for the same price as a 1500-word article

- People will pay more for single articles as they get more accustomed to buying them

1Pass did its first major installation for Project Syndicate at the end of 2015. This has not yet gone live, because Project Syndicate has chosen to first test a donations strategy for monetising its content.

The second major 1Pass installation, at the start of 2016, was for London’s Literary Review, where the 1Pass “buy” buttons have been styled to blend logically into the publisher’s pages: literaryreview.co.uk/its-the-taking-part-that- counts.

1Pass goes live on two sites in the spring of 2016: The website of another British monthly, The Oldie, which despite its ironic name is a lively and much-admired general-interest weekly, and a live trial with the London Review of Books. The company aims to roll out a new major installation each month.

“We want publishers to sell from their own websites, and so do they”, said head of sales Robert Cottrell. “The questions we get tend to focus on what single-article sales will do to subscription revenues. It’s a matter of pricing strategy. Single-article sales can even be used to drive subscription sales by raising the perceived value of the subscription. If you have the choice between buying the article for $1 or buying a subscription at a special one-time price of $10, which would you do?”

No company, though, has as much experience with publishers as Blendle.

According to Klöpping, the Blendle brain- storm was the answer to these questions:

What if…

- You could read all the journalism you care for in one place

- You would only need to register once to read all of what you do want

- You would only pay for the articles you were interested in and actually read and liked

- You’d get your money back if you didn’t like the story

- You wouldn’t be pressured to subscribe

- You wouldn’t be bombarded by ads

The brainstorm has translated into a micropayment model that works, delivering new revenue and new readers to Dutch, German and, soon, US publishers.

“But more importantly: It’s money from people who weren’t paying for journalism before,” wrote Klöpping. “My friends had never paid for music and movies, until Spotify and Netflix. And with Blendle, they’re paying for journalism, often for the first time in their lives.”

Here’s how it works: Users submit their payment details once (and only once) when they register and they automatically get a US$2.50 credit. Then, for each story they choose to read, a small fee is deducted from their account at the end of the month. If they don’t like the story, the fee is immediately refunded. Blendle users see a feed that is a combination of digital newsstand and friend-feed: stories curated by Blendle editors about the topics the user is interested in and trending stories, plus stories recommended by friends, celebrities and public figures.

Users can also scan all the stories in an issue of a magazine such as The Economist and pick out which articles to buy.

Publishers set the price (the average story costs twenty US cents). The publishers and Blendle split the revenue with 70% going to the publisher.

As important as the revenue is, Klöpping argues it is just as important that the “vast majority” of Blendle readers are under the age of 35, the very group publishers are having trouble attracting and desperately need in order to survive as they watch their core readership age and, well, pass away.

Also important: Blendle seems to have proven that mobile users will not only read long- form journalism on their smartphones, but they will also pay for the privilege! More than 60% of Blendle’s traffic comes from mobile.

Why does it work? It’s not just the ease and convenience of the micropayment system — it’s the golden triangle of choice, convenience, and curation, Klöpping told The Media Briefing. “What makes Blendle work in the end is that triangle between having a catalogue with all the major newspapers and magazines in a country that you’d expect; having one log-in, one registration that makes it easy to pay for everything [and] being able to find the content that is most relevant to you [though curated topics],” Klöpping said.

What lessons can publishers learn from the Blendle experience? Klöpping lists four:

1. Micropayments for journalism can work, but not for news. “We don’t sell a lot of news in Blendle,” wrote Klöpping in his anniversary post on medium.com. “People apparently don’t want to spend money on something they can get everywhere for free now. People do spend money on background pieces. Great analysis. Opinion pieces. Long interviews. Stuff like that. In other words: people don’t want to spend money on the ‘what’, they want to spend money on the ‘why’.”

2. Readers punish clickbait creators by demanding refunds. “BuzzFeed doesn’t work if people need to pay per article,” wrote Klöpping. “At Blendle we see this every day. Gossip magazines, for example, get much higher refund percentages than average (some up to 50% of purchases), as some of them are basically clickbait in print. It might actually be that micropayments will result in better journalism.”

3. Micropayments are a great measure of quality. Publishers and journalists can now see what kind of stories attract paying customers and what type of stories get the most refund requests.

4.Micropayment revenue is additional revenue, not cannibalism. “One year ago, some publishers in the Netherlands were pretty scared: Would the launch of Blendle result in cancelled subscriptions? We now know for a fact that Blendle doesn’t attract their current customers, but a new group that’s currently not paying,” wrote Klöpping.

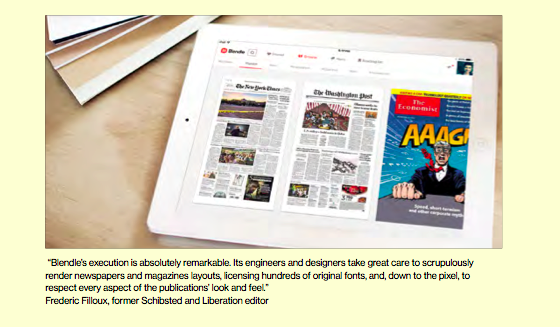

Even in the face of that success, critic Hoffelder’s headline was: “Blendle will be the next to show that micropayments still don’t work”. And an INNOVATION colleague of ours, former Schibsted and Liberation editor Frédéric Filloux, headlined his 2 November 2014 “Monday Note” blog post: “The New York Times and Springer are wrong about Blendle”. (The NYT had recently signed a distribution deal with Blendle.)

To Filloux’s and Klöpping’s credit, the pair built a relationship and in late 2015, Filloux changed his tune completely, concluding that “the company has been created by journalists”

To a person, the critics say the micropayment system is doomed not because of price or even technology, but because of mental transaction cost who fervently defend quality journalism and believe that great editorial must be paid for.

“Blendle’s execution is absolutely remarkable. Its engineers and designers take great care to scrupulously render newspapers and magazines layouts, licensing hundreds of original fonts, and, down to the pixel, to respect every aspect of the publications’ look and feel,” Filloux wrote. “Wherever the Blendle button is implemented, the reader will enjoy a friction-free experience… Blendle is thorough, agile and supremely confident.”

To a person, the critics say the micropayment system is doomed not because of price or even technology, but because of a phenomenon computer scientist Nick Szabo coined in 1996: Mental transaction cost. Szabo’s theory is that consumers put themselves through great angst trying to decide if something is worth buying or not. The critics also cite inter- net consultant and writer Clay Shirkey who wrote in 2003 that that mental transaction cost ironically increases as the price drops.

Maybe so. But times and consumer behaviours change.

Indeed, the same Clay Shirkey critics enlist to debunk micropayments wrote in a June 2015 Tweet about Blendle: “This is the first interesting micropayments idea I’ve seen in 15 years”.

It would seem that Blendle may have finally found a way to minimise the consumer angst associated with the mental transaction cost.

Their system is working, and it’s working with a pretty tough crowd (the millennials). Maybe it’s the millennials having been acclimatised to micropayment by iTunes. Maybe it’s the initial creation of an account against which to draw, or the low cost, or, more likely, the satisfaction with the product and the building of a habit of buying the same or similar products that have made the reader happy each time.

Or maybe it’s the money-back guarantee. How much angst can there be if you know you can get your money back if you don’t like what you bought? The initial purchase is not a commitment, it’s a conditional commitment. In essence, readers can postpone the final purchase decision until after they’ve “consumed” the product and found it satisfactory and worth the price. Or not.

As one Blendle reader wrote on The Digital Reader in mid-2015, “You choose to read an article, and yes, you pay for it, but there is no continuous conscious choice for me if I want a refund for each of these articles I read.” While some publishing company accountants might blanche at the thought of giving money back, Blendle’s experience is that fewer than one in ten of its customers ask for a refund. “We’ve taken away the fear that you spend 50 cents and then feel bad because the article was disappointing,” Klopping explained to the Poynter Institute.

The Blendle founders point out that refund requests tend to come from readers of gossip and clickbait type stories. They suggest that in addition to new revenues and readers, micropayment systems will actually encourage higher quality journalism rather than the empty calories of clickbait content.

Not everyone is a critic. As a matter of fact, multiple major publishers are getting behind Blendle’s unique micropayment system. The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and every single one of Germany’s major newspaper publishers are now on Blendle (not just a few major Ger- man newspaper publishers — ALL of them: 18 dailies and 15 weeklies) and more than fifty prominent magazine titles.

There are also niche publications, including 11 Freunde, a soccer culture magazine, Bilanz, that explains the world through the eyes of economists, and Neon, that combines beautiful writing with a progressive, young worldview, according to Blendle co-founder Marten Blankesteijn.

German journalists who tested Blendle prior to its launch there were impressed. In a post on Medium before the launch, co-founder Blankesteijn wrote: “Journalists tested the platform, calling it ‘very user friendly’ (Spiegel Online), ‘promising’ (Süddeutsche Zeitung), or even a possible ‘solution to all the problems of print media on the internet’ (Medienwoche).”

Blankesteijn quoted Mathias Blumencron, Frankfurter Allgemeine’s digital chief: “At first I thought, Blendle would present just another attempt of establishing an electronic cashier for articles,” he recently told me,looking back to our first conversation. “But then I discovered: This is really well done, it’s intelligent and it’s the first time that paying for articles could actually be fun. Blendle is basically a social network for discovering and buying the most fascinating articles of the day.”

Another major German publisher is also a convert. Julia Jäkel, CEO of German pub- lishing giant Gruner + Jahr told Filloux that she sees Blendle as a true component of a monetisation arsenal.

“Putting single articles on sale meets the needs of the iTunes generation used to picking singular pieces that interest them right there and then,” Jäkel told Filloux. “They are also used to making single payments — which is good news for publishers.

Even more important: starting off Blendle showed it doesn’t cannibalise existing subscriptions but attracts young target groups that haven’t turned to classic media offerings so far. So we hope to have opened up an additional channel for our audiences as well as an additional revenue stream for publishers.”

Some publishers see Blendle not only as a source of new revenue and readers, but also as an extremely valuable window into reader behaviour, especially those under the age of 35, a group most publishers don’t get to see interacting with their sites that often.

“One of the interesting things is these readers are the ones that you wouldn’t expect to pay for content. Still, they reward the depth and the uniqueness of our coverage, even though there is a profusion of free content available everywhere on technology,” Katie Vanneck-Smith, chief customer officer and global managing director at Dow Jones, told Filloux. “Stories [read on Blendle] are mostly tech-oriented; people select pieces on US technologies companies, new devices, etc. This is good for us since we invested a lot in our technology coverage — which represents an effort comparable to maintaining our foreign news bureaus.

“At this time, for the Wall Street Journal, this is mostly an experiment in which audience behavioural analysis is more important that actual sales figures,” she said.

Two major media companies who supported the Blendle concept put their money where

their mouths are: The New York Times and German publisher Axel Springer invested US$3.8 million in Blendle in October 2014. The investment helped fuel Blendle’s expansion into Germany.

Micropayment company CoinTent is also bullish: “Just as we’ve seen with music, movies, and game content, people are willing to pay for quality articles that they’re interested in reading if the price is right and the purchase experience is simple,” CoinTent CEO Bradley Ross said in a release. Ross believes that young people have been acculturated to making small and instant purchases for mobile games and in-app add-ons.

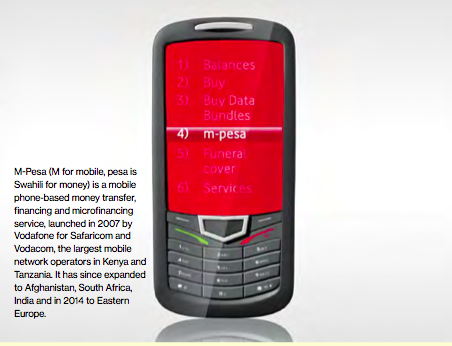

The success of micropayment systems such as M-Pesa in Africa, India, and Eastern Europe has given US and Western European tech and publishing companies additional courage to replicate their systems.

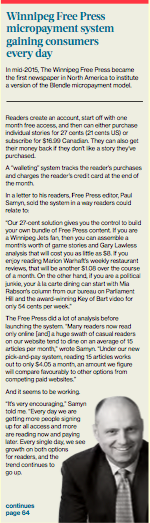

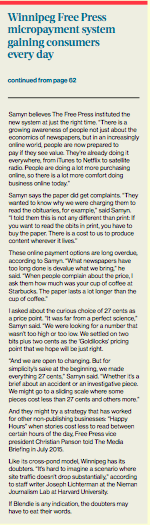

Two publishers in North America, The Winnipeg Free Press in Canada and Milwaukee Magazine in the United States, launched micropayment systems in the summer of 2015. It is too early to tell how those initiatives are faring (see the short story about Winnipeg Free Press micropayment system earlier in this chapter).

And in Europe, Nordic media giant Bonnier and micropayment company Klarna are partnering to offer Bonnier readers the option of a one-euro daily pass, and will soon offer individual stories for small sums.

At the end of the day, Blendle sees its future and that of the media as totally intertwined. “We can become the global paywall infra- structure for quality media,” he told Filloux.

So, let’s see: Who should we believe? The critics citing old failures and old psychological studies, or the readers, mostly new and mostly from our most desired demographic, who are happily handing over money to read content a la carte in ever-increasing numbers?

Give me a nanosecond.

On the face of it, it’s worth the effort. If it works — and it appears to be doing well al- ready — we’ve got another incremental source of revenue and, more importantly, a nose under the tent of the content consumption world of the under-35 age group.

Count us in as believers.

You?

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovations in News Media 2016 World Report.