20 Nov It’s time for a radical organisational revolution

Trying not to rock the boat too much has allowed the ship to rot. Start blowing up old teams, old job descriptions, old work!lows, old publishing schedules, old org charts, and old office spaces. No one and nothing can be exempt.

Good journalism is good business.

But good journalism — and a good business model — are only possible in 2017 if you completely reimagine your editorial operations.

Completely.

Top to bottom. Every person, every work flow, every schedule, every job description, every piece of equipment, every training regimen (or lack thereof), every beat, every publishing platform, every work environment. No one and nothing can be exempt.

Hiring an innovation director and a few developers or data scientists while leaving old editorial job descriptions, work flows, publishing practices, and even desk arrangements unchanged is an expensive exercise in futility. Without a whole-hearted, unflinching commitment to change, any reorganisation plan will ultimately fail.

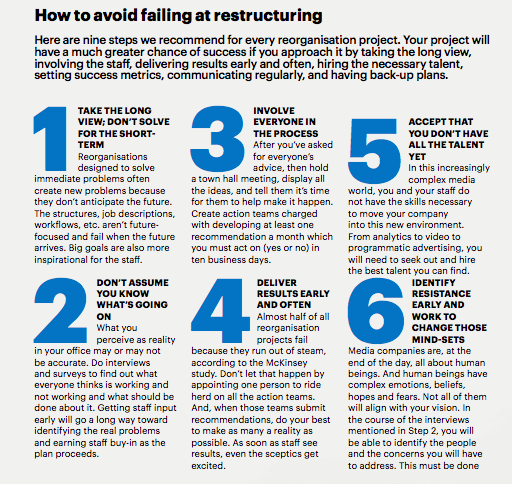

As a matter of fact, 77 per cent of all organisational redesign efforts fail, according to a recent McKinsey study.

What happens? Forty-four per cent run out of steam after getting under way, and another third fail to meet objectives or improve performance after implementation, according to the McKinsey study.

The consequences of that failure?

When reorganisation projects breathlessly announced by management as the salvation of the company run out of steam or fail, the company is actually in worse shape than before it started.

Hopes have been raised and then dashed. Staff have dedicated time and made emotional commitments only to be left at the altar. The company is months further behind in making the changes that might ensure its future. And any subsequent reorganisation effort will be greeted with massive, justified scepticism.

Even with an excellent editorial change plan, however, that reorganisation will fail unless it is rooted in a new company mission (so people know WHY they’re going through all the pain) and a clear, measurable business plan (so people can measure success that contributes to the successful financial future of the company).

Editorial restructuring must be undertaken both to enable great journalism AND to contribute to the profitability of the company. Otherwise, the change will lack direction, its success will be impossible to measure, and its results may have no impact on the sustainability of the company.

The reimagined editorial department might end up doing great journalism but if it’s not also converting readers to subscribers or delivering eyeballs to advertisers or contributing to other revenue-generating activities, the company’s future is limited or threatened.

On the other hand, if the restructuring plan matches the company’s strategic intentions, every element of the company — the structure, the processes, and the staff — will be set up to achieve strategic goals.

Every reorganisation project has different challenges, but one hurdle is universal: the suspicion that the plan is a smokescreen for layoffs. “It’s perfectly reasonable to ask whether this reinvention initiative is an excuse for more cutting,” wrote Boston Globe editor Brian McGrory in his April 2016 reorganisation memo to his staff. “The glib answer is that we don’t really need an excuse to cut. The revenue declines require it. The more involved answer is that even without declining revenue, we should still be exploring reinvention, given the massive advances in technology and massive changes in reader habits.”

Given those massive changes and how long things have been going downhill for media companies, you would think this need for total change based on new journalistic and business goals would be nothing new, and that, by now, media companies would be well into the process of constant change. Not so.

And that inaction is resulting in urgent, gut-wrenching, deep change.

“Because we haven’t had sufficient evolution, we now need a revolution,” wrote the team behind the Dallas Morning News reorganisation report. “Our entire approach to telling, presenting, and promoting our stories has to change to serve our increasingly digital audience. Every job in the newsroom must change. We must set different priorities.”

The folks in Dallas were far from alone. The year 2016 saw what Folio magazine called “convulsive” changes at some of the most iconic media brands in the world as well as at many others.

Time, Inc., Condé Nast, the New York Times, and others finally took the painful but necessary steps to organise themselves into content and marketing teams that could meet reader and advertiser needs and habits in an increasingly mobile age.

And, while each reinvention project had its own idiosyncrasies, all shared a similar approach, one that we at Innovation Media Consulting have been advocating for more than a decade: Organise editorial and sales teams by audiences or themes, not by brand, and consolidate services like creative and visual journalism to leverage talent across the entire organisation.

We believe the prescription for editorial re-imagining should also include that and more:

- Build a 24-7 hot news desk (we call it a “Radar” desk) to monitor news in your niches to feed your writers, websites, newsletters, e-alerts, messaging apps, etc.

- Build a social desk (we call it an “Echo” desk) to monitor mentions of news in your niches and mentions of your brand on social media

- Build a data journalism desk to create data-based stories, charts, and visual journalism

- Hire a chief data scientist to analyse data daily, weekly, and monthly, and make strategic and tactical recommendations on the same schedule

- Change your workflows and publishing schedules to match the reading habits of your audiences as evidenced by your data reports.

Even the New York Times, which had its organisational dirty laundry famously hung out for the world to see in a scathing internal report leaked in 2014 and which has been on a very public campaign to modernise ever since, admit- ted in early 2017 that it has not yet succeeded, according to the company’s most recent report.

In the “Journalism That Stands Apart” report (made public by the company in January), the NYT announced that: “For all the progress we have made, we still have not built a digital business large enough on its own to support a newsroom that can fulfill our ambitions… too often, digital progress has been accomplished through workarounds… our work too often reflects conventions built up over many decades, when we spoke to readers once a day,” wrote executive editor Dean Baquet and managing editor Joe Kahn.

“What’s illuminating for magazine publishers [about the NYT report] is that it reveals that the work of change is difficult and never truly finished,” wrote PubExecutive in a review of the report. “And it is fascinating to see how one of the largest, most respected, and in some ways, one of the most legacy-encumbered US media institutions is grappling with the challenge of transformation.”

The report recognised the organisational failures that have led to journalism failures. At the core of the organisation, like many other media companies, the report found that many at the NYT don’t know what their mission is, what their goals are, and who their audience is.

The report recommends that each section within the editorial department adopt specific goals and targets to create “a powerful focusing mechanism for reporters.” The report also laid out the need for clear goals to make it easier for editors and writers to know what success and failure look like.

“Every section should establish a vision plan that specifies what the team will cover, the target audience, how that audience will experience the section’s reporting, and what kinds of skills the group will need,” the report declared. This focus will have two benefits: It will make writers more effective and it will make it easier to“make choices about what we’re going to do and not do.”

Silos still survive at The Times and, indeed, dominate work flows. “High-priority coverage areas are spread across multiple desks, diluting them and limiting collaboration among journalists covering the same subjects,” Baquet and Kahn wrote. “Our health care coverage, for example, spans five departments and multiple print sections.

“No one starting a news organisation from scratch would separate the journalists covering the same subject,” they wrote.

Banquet and Kahn also recognised the text-heavy nature of the NYT in print and online. “We need to expand the number of visual experts who work at The Times and also expand the number who are in leadership roles,” the report’s authors wrote. Photographers, videographers, and graphics editors will “[play] the primary role covering some stories.” “We will train many, many more reporters and backfielders to think visually and incorporate visual elements into their stories,” they wrote.”

Other iconic media companies took those wrenching steps Folio cited to find their organisational way in the new digital era.

In October 2016, Condé Nast combined three departments previously silo’d within each brand. The newly consolidated creative, copy, and research teams now all sit together on one floor and service all titles. “The new team will include all editorial brand creative, art, design and photo, in addition to the creative teams from the businesses and 23 Stories [the Condé Nast branded content studio],” the company said in an announcement.

“These new, contemporary structures will make it easier to collaborate across edit, business and brand-to-brand, and truly unleash the collective power of our incredible company,” Condé Nast president and CEO Bob Sauerberg said in a memo to the staff.

A restructuring of the business side was going on at the same time. In an early 2017 internal memo, chief business officer and president of revenue Jim Norton told staffers: “To truly set our company up for success and take advantage of this potential, we’re modernising our revenue teams to simplify the way we work with our partners and better leverage the extraordinary talent in our company.”

Norton’s teams are now built around what he called “brand collections” and “client industries” instead of individual brands, and the people who were individual brand publishers now run “brand collections” and are called “chief business officers.”

Over at Time Inc., major changes were also the order of the day in 2016. In December, the magazine giant announced the creation of ten digital desks to improve the sharing of stories across ten verticals

“It’s recognising that audiences move around the web in ways that aren’t always brand-centric, and it’s different from picking up a copy of a magazine,” Edward Felsenthal, group digital director at Time Inc., told Digiday. Those ten new desks are: Celebrity, Entertainment, Food, Health, Home, News, Sport, Style & Beauty, Technology, and Travel & Leisure. Each desk will be led by an editor tasked with growing audience for their niche by coordinating coverage that can work across brands, according to a memo from chief content officer Alan Murray.

“Every writer and editor who covers one of the topics above will contribute to at least one digital desk, each of which will have a dedicated Slack channel where coverage can be coordinated 24/7,” wrote Murray. “While most routine assignments will continue to be handled within the brands, it will be the role of the desk leaders to ensure that we are collaborating in real-time, quickly seizing opportunities to win in social and search and steering our collective resources where we can have the most impact. We will track our audience growth not just across brands, but also across the desks.”

When he was named to the top Time Inc. editorial role, Murray said the current media universe requires that multi-title media companies create a more intelligent organisation of disparate brands and pool resources where it would add value across brands.

“It’s not clear that the best way to attack the market is always with a single magazine brand,” he told Vanity Fair. “We have all these different lifestyle brands. What this new structure lets us do is ask, is there a way to put all of our lifestyle content together or all of our health content together or all of our news content together in a way that better serves the mobile, social audience better?”

Many multi-title media companies face the same challenge: How do you become more efficient and leverage resources from multiple brands while not watering down the uniqueness of each title?

Murray and his Time Inc. team are walking that tightrope. “This is not a centralised editorial operation,” Edward Felsenthal, group digital director, told Digiday. “This is a structure that’s designed to build on what’s amazing about each of them.”

Part of that balancing act includes reducing the duplication of stories by writing a single piece and sharing that story across titles. As part of Hearst’s editorial reorganisation, the company set a goal of 20 per cent of each title’s content being shared content.

Time Inc. has not set a numerical target for sharing stories across titles because the company believes there is still a reason to have multiple stories about the same topic, Felsenthal told Digiday. Each title can bring a different angle on the same story, and can help leverage Time Inc.’s big reach in search to reach the widest possible audience, he said.

Like Condé Nast, Time Inc. also reorganised its sales department. Instead of focusing on individual brands, the sales structure was built around categories. This change also had an effect on editorial, as topic-focused sales drove a need to produce content to be placed in areas like health and finance rather than individual brands. This kind of thematic content can be produced to run across brands to match the cross-brand topic-related advertising.

Others have already moved in this direction. Back in 2014, Hearst created a central digital desk to feed its sister publications. That desk initially kept an eye on Hearst’s network of sites in the US for pieces that would work on other Hearst sites. Now that approach is being taken internationally where teams in Europe and Asia can see how all Hearst stories have performed and choose the ones that might resonate with their readers after being localised or in their original form. That process not only reduces duplication but also helps bolster the editorial offering of all Hearst sites and extend the life of the original work.

In early 2017, Hearst combined the beauty, fashion and entertainment departments at five magazines — Cosmopolitan, Seventeen, Redbook, Woman’s Day and Good Housekeeping, according to Business of Fashion.

In his 2017 New Year’s letter to all Hearst staff, Carey wrote: “Four years ago, we completely upended our strategy, and reimagined it, building one vast content ecosystem with the goal of sharing our most vibrant content across brands and geographies, without friction, cost, or permission. In 2016, the strategy truly matured: Our US digital team produced more than 80,000 pieces of content, ranging from short news items to impressive, long-form text/ video productions; unique visitors climbed by more than 29 per cent; revenue was up more than 31 per cent, and our social audience reached 122 million.

“In 2017, we will implement new strategies, including the formation of content hubs in the US and UK, where collaborative teams will produce content across multiple brands, and even geographies. This may at first feel awkward to some, but I am confident we will easily adapt, with the goal of strengthening our products and finding new efficiencies, while always striving for excellence,” Carey wrote.

As I mentioned in the beginning of this piece, reinventing legacy editorial and sales teams is not for the faint of heart, but neither is the media business these days. If you want to play in this game, you must ruthless- ly examine your editorial team and completely reimagine them for the digital, mobile and, soon, artificial intelligence world of the future.

You have run out of time for dilly-dallying and half measures. It’s now or never.

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovations in Magazine Media 2017 World Report.