09 Oct Monetisation: How the heck do you make in magazine media these days?

How the heck do you make in magazine media these days?

A famous American magazine publisher, Malcolm Forbes, once attributed his success in making money to the following strategy: “I made my money the old-fashioned way: I was very nice to a wealthy relative right before he died.”

Great plan.

But if you don’t have a wealthy relative, what is the solution to making money in magazine media in the 21st century?

The answer is: There is no single answer.

That is actually as it should be. Simple, single solutions are rarely a good idea.

That is actually as it should be. Simple, single solutions are rarely a good idea.

The media’s near-total reliance on advertising proved crippling when that primary source of revenue starting dropping precipitously. If there had been multiple sources of revenue, the ad loss could have been absorbed more easily.

So the answer is: Diversify.

Today, we have a rich buffet of monetisation options, some proven and some still on the runway. In this rather lengthy article (don’t try reading it all at once!), we are going to take a tour through 14 options for monetisation in magazine media:

1. Advertising

2. Ad blocking strategies

3. Reader revenue

4. Branded content / Magazine media

5. Distributed platform advertising

6. Ecommerce

7. Events

8. Messaging apps & chatbots

9. Mobile advertising

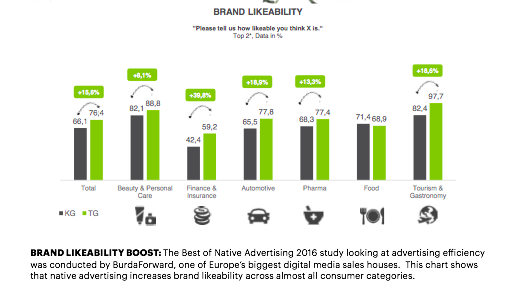

10. Native advertising

11. Newsletters

12. Programmatic advertising

13. Retail revenue

14. Video advertising

THE ADVERTISING MODEL

Lately some big name media players have said it’s time to give up on advertising-supported media. Others argue we just need a better consumer ad experience with less intrusive ad formats (native, out-stream). And some maintain advertising is still the best way to reach consumers.

“If you are doing the right things, it [the ad model] is a good business model,” Neil Vogel, CEO of about.com, told Digiday. “It works for us. When people criticise [ad-driven media], it is often because something in their model doesn’t work.”

Vogel isn’t alone.

“I think [the call for an entire overhaul of advertising] is a naïve statement by people who don’t understand the media business,” Troy Young, president of Hearst Magazines Digital Media, told Digiday.

Despite its troubles, there remains no format superior to digital display advertising, according to Ellen Harvey, digital editor of Book Business and Publishing. “Digital advertising is still one of the most efficient ways to drive revenue online and can connect advertisers with consumers on a massive scale or at an individual level,” wrote Harvey on the PubExec blog.

“Ad fraud and blocking aside, digital advertising still provides the best opportunities for advertisers to know exactly who viewed their ad and what actions they took after viewing that ad,” she wrote. “That is simply not feasible in print or television. Plus, digital advertising offers unmatched reach, allowing advertisers to target users wherever they might go on the web.”

Digital ads are working for somebody because digital ad spending, primarily for display ads, is still growing. For example, digital surpassed TV spending in 2016 in the US, according to eMarketer. Digital ad growth in 2016 was projected to be 18 per cent, including a 54 per cent increase in mobile and 49 per cent increase in social advertising.

If the model ain’t broke, it does, nonetheless, need some fixing. Everyone agrees that loud, intrusive, data-heavy, irrelevant ads are a problem and must go, but there’s another problem: context.

“What broke with advertising was its disconnection from community, just as with publishers,” wrote NewCo founder and CEO John Battelle on his company’s blog. “Sure, you can buy audience all day long. But without context?”

Battelle believes in advertising. In a post able, so it makes no sense entitled “We Can Fix This F*cking Mess”, he wrote: “if you don’t know who your community is, you’re screwed. I’m tired of all this nonsense about how the Internet’s business model is broken because advertising sucks. I call it bullshit. Advertising is a great business model. But it has become completely divorced from the creators and conveners of community – authors and publishers.

“But I deeply believe we can bring it back. And yes, I believe advertising has a role to play, Battelle wrote.

Some media companies have cleaned up their act and connected to their communities. And to demonstrate their faith in digital ads, those media companies are using an age-old strategy with advertisers: Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back!

In mid-2016, MPA, the US magazine media association, created a programme guaranteeing return on investment (ROI) for advertisers placing ads in a number of media companies’ publications.

Time Inc, Hearst, Condé Nast, and Meredith Corp. now promise advertisers an increase in brand sales and a positive ROI.

Meredith, which started experimenting with the system several years ago ran 35 campaigns with positive sales and ROI results: Sales in- creases were between 2 and 47 per cent, and the average ROI was US$7.45 for every US$1 spent.

Nonetheless, some critics say it’s time to try new variations on the old revenue model. For example, Jim VandeHei, founder of the political newsletter Politico, launched a new venture called Axios featuring a slate of newsletters and only short-form branded content advertising.

Axios won’t run long-form native ads, only words, photos and artwork that fit on one screen. “People want more digestible news. They want it shorter and more sharable, so it makes no sense to not have ads structured the same way,” VandeHei told the Wall Street Journal. “To keep doing the same thing as it has been done in media nowadays means death.”

He convinced ten heavy hitters to sign up for his new venture, including J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Boeing Co., BP PLC, and PepsiCo.

Some media companies think one solution is to offer readers the opportunity to pay for an ad-free experience.

In early January 2017, both the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times were reported to be exploring ad-free digital subscriptions, according to Digiday. Wired introduced ad-free access in 2016 for US$1 a week and told Digiday last spring that the experiment was going well. The Atlantic launched its no-ad experience offer of US$4.99/month in October 2016. The results are “exceeding our expectations,” a spokeswoman told Digiday.

Some say the new media world demands a new revenue model — one that doesn’t involve advertising. In early 2017, a high-profile media figure, Twitter co-founder and former CEO Ev Williams, dropped a bomb on ad-supported publishing. In a surprise announcement, he laid off 50 employees at Medium, an online publishing platform he launched in 2012, and abandoned ads entirely, declaring the ad-supported media system “broken”.

In February, Williams announced that to replace the ad revenue, he was going to launch a subscription model as an upgrade to the free Medium experience.

It’s not like Williams hadn’t tried — he’d invested in latest innovative ad formats, launched a native advertising business, and experimented with sponsored verticals. “The broken system is for ad-driven media on the internet. It simply doesn’t serve $1 people. In fact, it’s not designed to,” wrote Williams on his company’s blog. “The vast majority of articles, videos, and other spent ‘content’ we all consume on a daily basis is paid for – directly or indirectly – by corporations who are funding it in order to advance their goals. And it is measured, amplified, and rewarded based on its ability to do that. Period. As a result, we get… well, what we get. And it’s getting worse.”

Media figures like Williams see digital display ads as a rotten (and doomed) legacy of print.

“Many publishers… hope to find a way to replace declining print revenues with online advertising,” wrote The Economist deputy editor and digital strategy head Tom Standage on PressGazette.com. “This is a fantasy, and incumbent print publishers who try to move to a digital-ad model are mostly doomed to failure.”

“It doesn’t work now, and the chance of it working in the future will only get smaller, as ad-blocking becomes more widespread and the shift to mobile consumption pushes down advertising rates,” Standage wrote.

“Publishers live in hope that some new kind of advertising will be invented that will somehow pay the bills,” he wrote. “It seems unlikely. Video advertising, native advertising and other forms of advertising provide only small incremental revenue streams for publishers, and the majority of online ad spending in the west now goes to Google and Facebook, not to publishers.”

Standage’s answer: Reader revenue (more on that below).

AD BLOCKING

Why is ad blocking a topic under “Monetisation”? Isn’t ad blocking the antithesis of monetisation?

Yes, indeed.

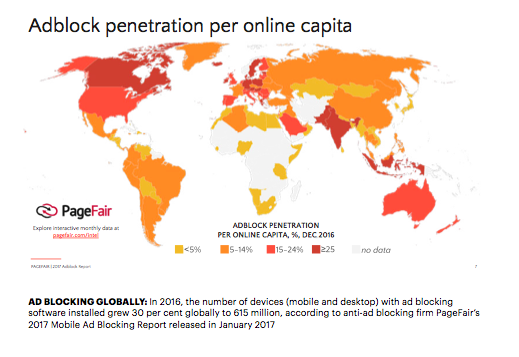

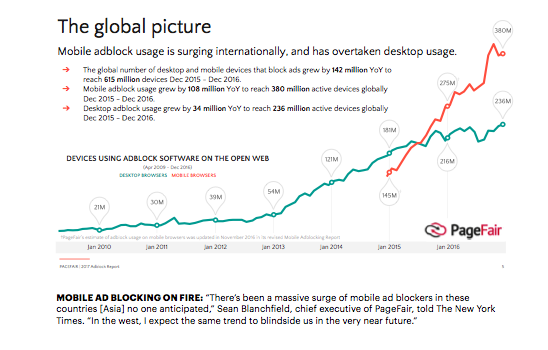

As a matter of fact, if left unresolved, ad blocking could cost media companies between US$16b and US$35b by 2020, according to In- forma Group’s research arm Ovum. Consumers in ever-increasing numbers are using ad blockers. In 2016, the number of devices (mobile and desktop) with ad blocking software installed grew 30 per cent globally to 615 million, according to anti-ad blocking firm PageFair’s 2017 Mobile Ad Blocking Report released in January 2017.

Asia accounted for a stunning 94 per cent of worldwide mobile ad blocking and usage there grew by 40 per cent last year, the study found.

“There’s been a massive surge of mobile ad blockers in these countries that no one anticipated,” Sean Blanchfield, chief executive of PageFair, told The New York Times. “In the west, I expect the same trend to blindside us in the very near future.”

On the other hand, ad blocking on desktop is restricted mainly to the United States and Europe, where ad blocking increased 17 per cent in 2016 to 236 million devices.

To date, media company efforts to defeat the ad blockers have met with limited success.

Lawsuits don’t work. The makers of Adblock Plus are undefeated in court, having won all six court cases brought against them by German media companies claiming that ad blocking violates German law.

Tech weapons offer only temporary relief. It is a whack-a-mole game of constantly creating ad formats to block the blockers, only to have them figure out a work-around. It’s an endless, no-win game.

For example, when media sites started blocking readers who had ad blockers, it took no time at all for hackers at a site called ReekSite to create an “adblocker-blocker”. The software is a JavaScript file and filter list that anyone can download that empowers users to keep their ad blockers on and still see content on media sites that blissfully think their software designed to keep ad-blocking users away is working just fine!

Some media companies and websites have had success with either appealing to the better nature of their readers or offering an “ad-lite” experience.

Forbes has achieved great results by asking readers to turn off their blockers in exchange for that “ad-lite” experience. Some media companies block all or some of their content when a user tries to access their site. When a user who has installed ad-blocking software opens a page, they are greeted with a message to the effect that ads pay for the content and, if they turn off their ad blockers, they can continue to read.

Readers have responded positively. Bild got 66 per cent of blockers to turn off the software, Forbes got 42 per cent, IDG 37 per cent, GQ got 30 per cent and Schibsted Norway 20 per cent.

Facebook and live streaming service Twitch use coding on ads that makes them appear like

regular content on the back end. As of early 2017, the ad blockers hadn’t broken that code. But it’s probably just a matter of time.

Media companies can also turn to an array of companies willing to write software to get around the ad blockers, including PageFair, Sourcepoint, Secret Media, and Admiral. All promise media companies one thing: to help recapture revenues lost because of ad-blocking users.

For example, Admiral’s software loads media companies’ ads onto web pages in a way that is currently undetectable by most ad-blocking software. This strategy is often referred to as “reinsertion” because the media company is, in effect, reinserting ads into pages that otherwise would be stripped of its ads by the ad-blocking software.

But with so much money at stake, you can rest assured the ad blockers will figure a way around every new trick media companies and their allies develop. And so the whack-a-mole game never ends. Even if we could win, what do media companies gain by outfoxing the ad blockers? How do they and their advertisers benefit from forcing ads on readers who have said they don’t want them?

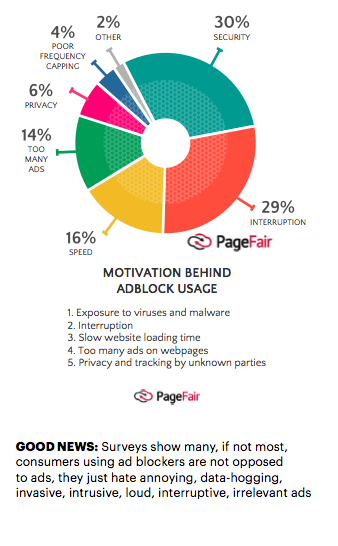

The good news is that surveys show many, if not most, consumers using ad blockers are not opposed to ads, they only hate annoying, data-hogging, invasive, intrusive, loud, interruptive, irrelevant ads (did I miss any?).

If media companies make the ad experience more useful and pleasant, everyone — publishers,

advertisers, and consumers — win. Forbes’ experience with the “ad-lite” approach has found that its ad-lite users stay on a page longer and engage more when they are spared from intrusive ads that hit them the minute they open a page, or start playing video automatically, or load slowly.

Like many media companies, Forbes has a lot at stake here: roughly 80 per cent of its revenue comes from digital ads.

“We’re very committed to the advertising-supported site,” Forbes chief product officer Lewis DVorkin told the Wall Street Journal. “We’re trying many things.”

One of those things is native advertising products such as Forbes’ BrandVoice program, which allows marketers to publish content to its site. Forbes allows those marketers access to the company’s content management system, bypassing the “ad-serving” systems. Because of that, the native advertisements are not seen as ads by ad blocking software.

The real solution, however, is not to outfox the ad blockers but to fix the ad problems that motivate consumers to install ad blocking software in the first place. If we do that, the ad blocking crisis will end up increasing monetisation in effect.

“On the surface, ad blockers sound like marketing nightmares,” wrote Chris Zook, digital marketing specialist at marketing company WebpageFX. “But at their core, they’re industry challenges that give marketers the chance to innovate and adapt.” Fortunately, fixing the ads is not rocket science. Make ads meet the same standard of excellence you expect of your editorial content. Make them fast, relevant, intelligent, useful, data-light, non-invasive, etc. and readers will turn off their ad blockers. But not before.

READER REVENUE

The combination of the decline of print revenue and the damage done to the digital advertising model by ad fraud and ad blocking is forcing magazine media to consider revenue alternatives.

“Publishers will have to look for other sources of revenue,” wrote Economist digital strategy head Tom Standage on PressGazette.com. “Conferences? Travel? Financial services? Philanthropic supporters? Diet clubs? All these have been tried, but again the resulting revenues are merely incremental.”

“The obvious answer is to ask readers to contribute,” wrote Standage “That, in turn, means having content that people cannot get elsewhere.”

Standage and others argue that if a media company is doing its job — creating valuable content its audience cannot get anywhere else — readers should be willing to pay for it. Some media companies that have tried are succeeding, with reader payments beginning to provide a healthy percentage of their revenues.

The Atlantic, New York Magazine, and Bloomberg Businessweek all experienced subscription revenue in 2016 that was in the neighbourhood of 60 per cent of total revenue, according to Pew Research.

In the newspaper world, three of the largest US newspapers, the Washington Post, Wall Street Journal and New York Times, now charge for access. Nearly a third of US daily newspapers now have some form of fee for digital access, according to the Pew Research Centre.“As someone who cares deeply about independent journalism, I love the idea that our most important financial relationship is with the reader, not the advertiser,” wrote Lydia Polgreen, editorial director, NYT Global, on her Medium blog. “It clarifies our mission and helps us make tough choices about how to spend our precious editorial resources.”

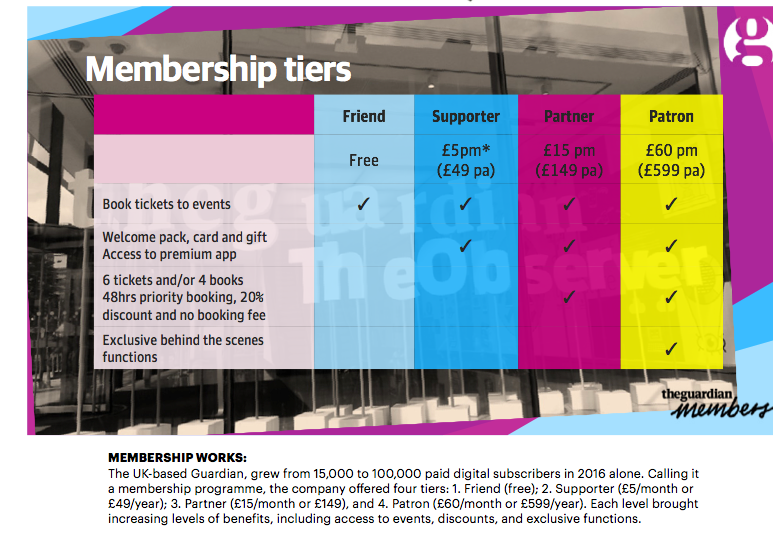

Another major newspaper, the UK-based Guardian, grew from 15,000 to 100,000 paid digital subscribers in 2016 alone.

Calling it a membership programme, the company offered three tiers:

1. SUPPORTER: For £5/month or £49/year, readers get access to the digital edition and the

opportunity to buy tickets to Guardian events.

2. PARTNER: For £15/month or £149/year, readers get digital access plus six tickets to Guardian Live events (or four Guardian-published books) per year plus priority booking and 20 per cent discount on Guardian Live, Guardian Local and most Guardian Masterclasses, as well as a welcome pack and gift.

3. PATRON: For £60/ month or £599/year, members get all of the above plus invitations to a small number of exclusive, behind-the-scenes functions.

The Guardian tested 30 different messages on different platforms to find the messages that drove the most subscriptions. One early pitch focused on The Guardian’s history, but it drove more one-time contributions than subscriptions. When the company changed the message to focus on its independence and the cost of producing quality journalism, conversion rates soared, according to the publisher.

The Guardian also changed locations for the message, testing end-of-article placement and using banner ads as well as links inside stories and pop-ups for visitors using ad blockers (this last tactic was very effective, the company reported).

While The Guardian tried social media to promote memberships and contributions, the highest conversions came from its own properties and email newsletters, the company said.

Condé Nast and others offer memberships to high-end subscribers. The Condé Nast Wired Group (Wired, Ars Technica, and Backchannel) is charging US$4,000 a year for access to in-person and web events with tech startups, access to other peer-to-peer events with people like themselves, bespoke newsletters, and other perks.

The National Journal is charging US$5,000 to US$50,000 a year, depending on the size of the organisation, for specialised research and tools plus networking events. Slate offers Slate Plus to give members special access to its journalists and events for US$35 a year.

Community is part of the benefit of the US$399-a-year subscription to tech news and features site The Information. “If you think about the places where people spend their time in media, they spend a lot on music and a lot on news,” she said. “So it made for a very positive association.”

BRANDED CONTENT / IN-HOUSE AGENCIES

If a boat springs a leak, it’s a really good idea to find the hole and plug it… quickly.

Not long ago, publishers noticed a particular revenue leak (among many): Folks formerly known as advertisers were taking marketing matters into their own hands.

“Our customers were becoming our competitors, which is a weird place to find yourselves in,” The Guardian’s commercial strategy director Adam Foley told Digiday.

So the Guardian got into the branded-content studio game in 2014 with a new unit called Labs. Other legacy media companies are also spending significant sums to build “branded content” niche businesses within their walls and turn them into new revenue drivers that in some cases already represent as much as 15-20 per cent of total digital revenue.

“More and more publishing houses are opening up their own in-house content marketing agencies to help better serve the advertisers whose dollars they so desperately want to keep in the face of declining traditional print advertising revenues. Vice, Buzzfeed, Hearst, the New York Times… it’s difficult to name a major publisher today that doesn’t operate a branded content studio,” wrote Lauren Sherman, New York editor at The Business of Fashion, in a January 2017 piece. “Since the launch of 23 Stories [Condé Nast’s branded-content studio launched in January 2015], Condé Nast has quadrupled branded con- tent revenue, and branded content is on track to make up 15 per cent of the company’s overall advertising revenue for 2016.”

“We are far ahead of our target this year in terms of revenue,” Josh Stinchcomb, senior vice president and managing director of 23 Stories, told Sherman. “However, what’s equally import- ant to me is that, now that we’ve done really good work in a lot of different categories, the results that we’re seeing are justifying the investments. We’re seeing engagement rates that rival, if not exceed, editorial norms. This content is resonating as deeply as anything else.”

Sherman’s experience is reflected in the industry. Almost three-fourths of the marketers surveyed by the trade group Content Council said they believed branded content is more effective than traditional magazine advertisements.

Hearst, too, has its own content marketing agency, Hearst Branded Content Studio, which creates content and sells deals across multiple properties, even tailoring content for the same campaign uniquely to each brand audience. Fully 95 per cent of Hearst’s major campaigns include branded content, and it’s the fastest-growing revenue category, Hearst Magazines Digital Media svp and chief revenue officer Todd Haskell told Business of Fashion. For example, a project promoting Coach’s Spring 2016 collection ran across Marie Claire, Harper’s Bazaar and Elle, with three very different approaches.

Great branded content also makes for great reader engagement, engagement that carries over to the ads on the page. Display ad click-through rates on branded content pages from Hearst Digital Studios are two-to-three times higher on average compared to ads on pure editorial stories, according to Haskell.

“I think the reason that we’re seeing brands in fashion, luxury and beauty work with us is that there’s a recognition that what we, as an organisation, do exceptionally well is understand what drives consumers to engage with content online,” Haskell told Business of Fashion. “To take action.”

“Branded content studios exist because consumers are increasingly only engaging with brand messaging that has value for them,” James McNally, director of digital strategy at marketing agency TDT told MobileMarketer.com. “For media organisations to attract ad dollars, they need to offer ad vehicles that give the viewer comparable value to their non-advertising content — i.e. the stuff that got those viewers’ eyeballs to their website in the first place.

“Creating content that is compelling to the viewer while also pushing a brand message is far more involved than simply slotting creative into IAB ad slots; it requires dedicated teams to leverage creative, tech, and marketing expertise, and to account manage the complexities of the native advertising conception and sales process,” McNally said.

The best branded content is not cheap to produce, however. The research, writing, interactive digital, and sophisticated video pieces are expensive and time-consuming to produce.

The competition is also intense, not only from agencies but also from digital natives like Vice Media and BuzzFeed who have been creating branded content for a long time as the core of their very successful business model.

DISTRIBUTED PLATFORM ADVERTISING

For media companies to put their content any- where but on their own sites takes a leap of faith, a leap that can be made less risky by a reward.

But rewards have been slow in coming. Some distributed platforms are proving to be lucrative while others have yet to even remotely live up to their potential.

In January 2017, Digital Content Next (DCN), an industry group representing digital companies, released its Distributed Content Revenue Benchmark Report.

Right up front, DCN framed the dilemma: “Distribution platforms present new challenges and opportunities for the premium publisher. On one hand, they give publishers a way to reach new audiences and monetise them. On the other hand, they provide a dependency on third-party partnerships and relinquish the direct consumer relationship.”

The report opened with what some considered under-whelming results: For all its promise, revenue from distributed platform publishing represented only US$7.7m or 14 per cent of total first-half of the year 2016 revenue on average for the 17 DCN members (10 TV/cable companies and nine newspaper, magazine and pure play companies) providing revenue data on distributed content.

From the perspective of magazine media, the news got worse. Video revenue, which rep- resented 85 per cent of the total, was driven by TV/cable companies’ OTT monetisation. The remaining 15 per cent sliced across social media, Google AMP and syndication. Those aren’t the kinds of numbers that would seem to justify the expense of publishing on multiple social platforms.

Some publishers are so frustrated with the inability to make money on distributed content platforms, they’re considering pulling out altogether.

“Platforms are the audience king,” Nich Ascheim, senior vice president of digital at NBC News, told Digiday. “One of the most important sources of that content is us, and if that relationship continues to be where we can’t make it economically viable, it makes sense to take our content off there.”

Media companies are looking for significant changes, especially from Facebook and Google. “There’s real meaningful change that needs to happen. It’s fundamentally about monetisation,” Mike Dyer, president and publisher of the Daily Beast, told Digiday.

Short of pulling out, some media companies that had earlier jumped on every shiny new platform are now deprioritising features that haven’t monetised well or scaled, such as Face- book Instant Articles and Facebook Live video, Twitter Amplify, YouTube Red and Apple News, according to the DCN report.

The frustrating inability to monetise distributed content is compounded by the platforms’ unpredictable and seemingly erratic penchant for changing the rules. When that happens with little or no warning, the media companies that have built teams and processes around the old way of doing things have to scramble to change course.

The DCN report began with the elephant in the room: Facebook. The social media giant offers media companies the most opportunities for publishing content “off-site”: Instant Articles, Suggested Video, and Branded Content, Facebook Live, and Audience Engagement.

Here’s the DCN report’s break- down of the pros and cons of each:

Facebook Instant Articles

“Facebook Instant Articles has program restrictions, such as the number and types of ad units, that make it hard for publishers to monetise at rates comparable to their own sites, as well as measurement limitations which hinder comparisons of financial and content consumption performance between the platform and publishers’ own sites,” the report stated.

“Instant Articles are hosted on Facebook, thereby reducing traffic to publishers’ sites through linked articles,” the report said. “Despite this, there are several Instant Articles features attractive to publishers. These include significantly faster load times compared to publishers’ mobile sites, publisher ability to integrate ad serving (e.g. Double-Click for Publishers (DFP)), and third-party measurement services (e.g. Nielsen, comScore, Moat, Adobe Analytics Omniture, Google Analytics), the potential to scale relative to other opportunities, and favourable terms allowing publishers to keep 100 per cent of their own ad sales. Publishers interviewed, however, report lower levels of monetisation through Instant Articles than on their own sites.”

Facebook Branded Content

Branded Content was the most popular monetisation strategy on Facebook for survey participants. “Print-based and pure play members reported higher levels of interest based on the relative importance of branded content in their overall monetisation strategies,” the report stated. “Attractive features include the support of both print-based and video content, the zero per cent revenue share with Facebook, and publisher control in placement in the feed.”

Facebook Audience Extension

Nine of 17 publishers reported monetisation in Q4 through Audience Extension on Facebook against branded content. “This approach allows publishers to use Facebook’s data for targeting, to scale branded content programmes, and to respond to marketers’ appetite for social media, without having an explicit agreement for content or advertising with Facebook,” the report said. “While publishers keep 100 per cent of what they are paid by the advertiser, they do pay for placing branded content into the feed, essentially benefiting from the lower rate they pay Face- book and higher rate they charge the advertiser. Publishers report margins of over 50 per cent with Audience Extension. Publishers with subscription products are successfully using Audience Extension in combination with targeting to drive subscription sales.”

Facebook Live

“Facebook Live has yet to scale or prove a revenue model beyond the publisher production guarantees,” the report concluded. “While 17 publishers report using Facebook Live, only two received fees for meeting quotas for video minutes produced the first half of 2016 as Facebook Live launch partners.”

Looking for other financial support of Facebook Live, “six publishers report selling sponsorships or product placement against Live con- tent,” the report stated. “others have found no takers. Another fundamental publisher concern is Facebook’s lack of success in creating largescale audiences around live events.”

The report was decidedly mixed in its review of the other distributed content platforms:

• GOOGLE ACCELERATED MOBILE PAGES AMP : “Google AMP is gaining ground with pure play and print publishers: While revenues reported for Google AMP in the first half of 2016 were minimal, some accounts of early testing are quite positive,” the report stated. “Nine publishers report Q4 use of Google AMP and monetisation — through their own ad sales, while some are also back-selling through programmatic sales.”

• TWITTER AMPLIFY: “Twitter Amplify has not scaled,” the report stated. “Publishers’ primary goals for Twitter are geared more to content promotion and driving site traffic as opposed to off-platform content distribution and monetisation. While nearly all publishers report being active on the platform with multiple accounts, only 10 reported monetisation in Q4, including a few publishers that monetised only through Twitter’s sales.”

• SNAPCHAT: “Snapchat exemplifies many of the characteristics that make third-party platforms difficult partners for publishers: total control over the selection of Discover partners by the platform; onerous publisher guarantees; a silo’d publishing system lacking ad serving and tracking integration; ads that viewers can quickly swipe past; overall lack of responsiveness to publisher requests; and rapid changes in monetisation models,” the report stated rather brutally. “Snapchat recently announced a new licensing model for Discover channels which may translate into a limited upside for monetisation by publishers.”

• YOUTUBE: “Of 16 publishers [that] reported distributing on YouTube through their own channels, 14 in Q4 are monetising – 11 through their own sales efforts, and 14 through YouTube. YouTube has proven a fickle partner as demonstrated by recent problems publishers have had with YouTube prioritising its own skippable video ad inventory (i.e., units that allow the viewer to skip the ad after five seconds) over non-skippable partner inventory.”

The other big news in distributed content publishing is Facebook’s announcement that it may allow mid-roll ads in videos, giving publishers 55 per cent of all revenue, the same split YouTube offers. Facebook has historically forbidden all pre-roll ads on videos. Some media companies welcomed the news. “This gives us an opportunity to make more content and make it a more investable channel,” Michael Hannon, vice president of revenue at digital content and services company Purch, told Digiday. “If the data ends up proving that it works, why wouldn’t we [make more Facebook videos]?”

This is especially welcome news for media companies that have had trouble monetising video on Facebook.

But for some, the news brought trepidation, despite the restrictions Facebook was reported to be considering: No ads longer than 15 seconds, no ads on videos shorter than 90 seconds, no ads until the 20-second mark.

“Ads can frustrate users. While it is unclear whether or not users will be able to identify whether or not a video contains an ad, failure to do so could cause users to stop watching the video completely,” declared Business Insider in an opinion piece. “The answer to the long-asked question of how Facebook plans to monetise videos may be here, and users aren’t going to like it,” wrote Social Times editor Dave Cohen in Adweek.

ECOMMERCE

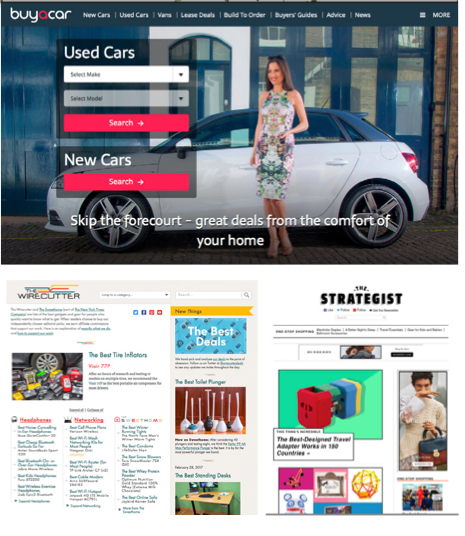

Ecommerce is not new, but scaled, successful ecommerce for legacy publishers is new.While digital natives like Gawker Media and Vox Media have succeeded for years, legacy publishers have mostly shied away.

Now, however, legacy media companies are jumping in with both feet, and none more flamboyantly than The New York Times.

With resources few can match, The Times dived into ecommerce in a very big way in the autumn of 2016 with the US$30m purchase of the extremely popular and successful ecommerce site Wirecutter and its sister site, The SweetHome.

Both sites have robust reputations for respected reviews and recommendations of technology and household products. Both retain scientists, technologists and other experts to review and often lab-test products before recommending them. It was that solid reputation and outstanding financial success (estimated US$200m 2016 sales) that appealed to the Times.

With Wirecutter and SweetHome, The Times acquired a massive collection of high-quality product reviews, adding to the service journalism The Times has been building in its own verticals: Cooking (recipes), Watching (TV and film), and Well (fitness and health). Wirecutter and TheSweetHome also give The Times the wherewithal to expand ecommerce into many more verticals. “The Times is excited to think we can apply their approach for product recommendation to a lot of different spaces that they [Wirecutter and Sweethome] are not currently in,” NYT Beta development group vice president Ben French told Politico.

“We have instruction-like guides on the Cooking app that help people learn how to cook and among those guides are guides to sharpen people’s knife skills,” French said. “And Sweet-Home has great knife recommendations. We feel like if you’re on that page, it makes perfect sense to provide that kind of information to readers.”

French said that the site is projected to generate about US$200m in sales this year, which would put its revenue around US$10m or US$20m. The Wirecutter’s conversion rate is particularly high, at about 15 per cent, he said.

Over at New York magazine, they launched ecommerce site “The Strategist” in October 2016. Dating back to the “The Savvy Shopper” in the magazine’s very first edition in 1968, the title has done service journalism before service journalism was a thing.“Service journalism is part of New York’s DNA,” New York’s deputy editor David Haskell told journalism site Nieman Lab. “The idea over its entire history is that the city is vast and thrilling and overwhelming sometimes, and there’s a lot of usefulness that can come from smart, direct, witty advice about how to navigate it properly.”

The Savvy Shopper has “trained a whole generation of editors here to be very good service journalists,” Haskell said. Given the success of The Savvy Shopper for New York City shopping, new CEO Pam Wasserstein made one of her first moves the launch of the commerce site for internet shopping.

“We realised that there was an opportunity for the same kind of service journalism we’ve been perfecting and focusing on for decades to be applied to internet shopping,” Haskell told Nieman Lab.

“Since we had already been dipping our toes into affiliate ecommerce revenue for a few years [with strong clickthrough and conversion rates], we knew there was untapped potential if we really put strategic thinking and resources behind it,” Wasserstein told the Nieman Lab.

“[The Strategist] is edited by people (not robots), and is designed to surface the most useful, expert recommendations for things to buy across the vast ecommerce landscape,” according to a company announcement. “Most online shopping advice comes in the form of not particularly helpful roundups and slideshows. Our hope is to find the stuff out there that is actually worth buying – products that are really good and that we fully believe in.”

Because of the luxury nature of New York’s recommendations, The Strategist ecommerce program doesn’t rely as heavily on Amazon as other programs like Gizmodo and the New York Times’s Wirecutter do. For all those non-Amazon items, New York uses ecommerce site Skimlinks and the Bam-X affiliate program which, according to its website, aims to “connect retailers with organic stories on premium publishers in a scalable, optimised way.”

Editors working with The Strategist make their decisions without any influence from the business side. “If our editors fall in love with an item that’s outside of that [affiliate revenue] universe, we’re still going to write about it,” Haskell told Nieman Lab. “We only think there’s a strong and enduring business here if we can be 100 per cent behind every product we recommend.”

Ecommerce couched in an editorial recommendation engine is not limited to a couple of New York City based publications.

China’s Quality and Certification Magazine takes the same approach as Wirecutter: content based on high-quality third- party testing and certification leading to online sales. But Quality and Certification go where few other magazines have gone: messaging apps. Messaging apps are not as big in the west and media companies there have been hesitated to jump into such a personal mode of communication.

But in China, messaging apps have been big for a while and the Chinese readers apparently enjoy hearing from brands with something valuable to say. As a result, Quality and Certification have managed to accumulate 220,000 followers on WeChat.

Quality and Certification offers an online shopping experience that includes the full testing report or certification of each product as well as its certificate and the option to buy products in 200 categories of goods with more on the way. “Nowadays, consumers pay a lot of attention to the quality of products and services,” said the president and chief editor of Quality and Certification Magazine Wei Liang. “We integrated the product information, logistics, and purchasing service into one platform by sending messages to get users, then introduce quality knowledge, transfer detection and certification concept for them, in a way that makes the process widely scalable.”

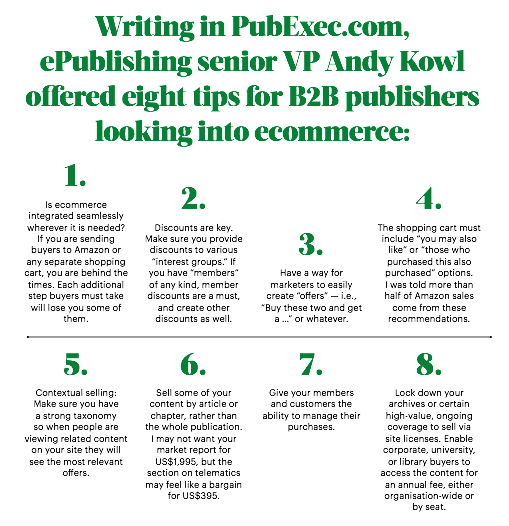

Australia’s Fairfax Media launched an ecommerce site for quality Australian-designed products in the fall of 2016. Like The Times, Fairfax felt they had to acquire expertise, and they did so by hiring Trudi Jenkins, the co-founder of ecommerce startup hardtofind.com.au.

Now, as Fairfax digital commerce director, Jenkins hopes to double ecommerce sales in six months with a collection of more than 1,000 products ranging from art, clothing, and accessories to home wares and garden goods. Fairfax makes the experience appealing to its subscribers by giving them a 20 per cent discount.

TheStore.com.au is actually a platform for Australian artists, designers, manufacturers, etc. to sell their goods. “We don’t buy any stock. We don’t warehouse any stock. We basically create a platform for people to sell their products and we can take a percentage,” Jenkins told NewsMediaWorks.com. The sellers handle the filling and shipping.

Going even further, UK-based Dennis Publishing (more than 35 magazines and websites) jumped on an opportunity to purchase online car dealer BuyaCar in 2014 and integrated the ecommerce business with its portfolio of automotive websites, “We already had an audience of in-market car buyers and relationships with the car brands,” James Tye, CEO at Dennis, told The Guardian. “We saw a change in consumer habits and felt there was an ecommerce potential. The margin is sizeable and we’re leveraging a really important audience through our websites.”

After just three years, Dennis now sells nearly 200 cars a month and BuyaCar generates 16 per cent of the company’s total revenue, according to The Guardian. BuyaCar and the other Dennis ecommerce ventures now generate more than half of the company’s digital revenue, according to Tye. Ecommerce has become a major success story for the company.

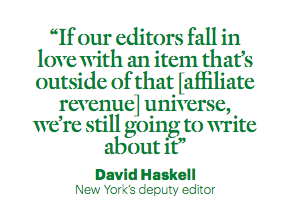

If you’re a B2B media company, you have even more ecommerce options. For B2B media, the top ecommerce items are subscriptions and renewals, followed by paid webinars, workbooks, near real-time data, training and continuing education credits, market reports and in-depth regional reports, archive site licenses, and of course, books and CDs, according to Andy Kowl, senior vp of publishing strategy for the enterprise publishing system company ePublishing Inc.

EVENTS

Here’s a media industry bromide: Events are insanely profitable for media companies.

Here’s a media industry head-scratcher: Despite those profit levels (averaging 30-40 per cent, according to the Local Media Assoc.), events still only represent a single-digit percentage of media company revenues for consumer media companies.

In 2004, events represented just 2.4 per cent of revenue for B2C media; ten years later, events are “up” to 7 per cent, more than double but barely more than a blip, according to Folio’s annual B2B and B2C CEO surveys.

For B2B companies, events contribute more than twice that (15.6 per cent), also double what events added to the bottom line in 2004 (8.4 per cent), according to Folio. Some media companies are proving the financial power of events. UBM, the giant media company that’s adopted an “events-first” strategy, reported revenues for the first half of 2016 at just over US$500m, with by far the largest chunk — US$405.8m — coming from its events business.

In a mid-2016 earnings report, UBM reported events produced profits of nearly 30 per cent. At B2B publisher Penton, events are now the largest revenue stream. In the last ten years, print revenue and event revenue have changed places: Print has gone from the largest source (73 per cent) to the smallest (24 per cent), while events have gone from the smallest (16 per cent) to the largest (40 per cent), according to Penton CEO David Kieselstein speaking to Folio.

Kieselstein told Folio he sees a multiplier effect when migrating revenue to events and digital; the margins on both are far superior to print. In 2016, 52 per cent of Penton’s EBITDA will be events, 38 per cent digital, and just 10 per cent print, he said.

The average profit margin for a separately operated events division run by a media company is 40 per cent, and those divisions hit that number within as little as two years, according to Local Media Association (LMA) president Nancy Lane speaking at the 2016 Borrell Local Online Advertising Conference in New York.

Media companies have almost all the assets needed to run events: market penetration, brand recognition, diverse portfolios of products, creative people, an existing workforce, and community partnerships, according to Jason Taylor, Gatehouse Media‘s western US president, told the Borrell Conference.

More than one-third of US publishers believe that events are the single revenue source most likely to increase in value in the next two years, according to Ukman. “The event business is a wonderful business,” HMP Communications CEO Jeff Hennessy told Folio. “It’s proven, well-established, and it’s got its own ecosystem. It’s wonderfully diversified when you think about attendee revenue, sponsorship revenue, advertising revenue, exhibitor revenue.”

Events should be at least “the third leg of the media stool,” according to LMA’s Lane. Media companies should treat events as a separate business unit and allocate resources initially as if it were a startup. Here are Lane’s tips for events success as told to StreetFightMag.com:

- Separate teams are critical to success

- Bringing a cause or charity into events can in- crease ticket sales and sponsor revenue

- B2B events are big hits, as are events around dining and food

- Promotions and editorial content can be converted into events, e.g., best-of lists and contests can become banquets and awards presentations

- Start with a narrow focus on categories the media company “owns” e.g., New York magazine launched Vulture Festival based on the success of its entertainment niche: vulture.com (nearly 7 million unique monthly readers). Vulture Festival is a profitable venture with 18 ticketed events and 15 sponsors)

- Event management software is essential

MESSAGING APPS & CHATBOTS

Remember when we thought social media was a big thing? Not so long ago, right?

Well, messaging apps have now surpassed social media in terms of global users (it actually happened in March 2015, but few people were paying attention).

Over 2.5 billion people have at least one messaging app on their smartphone, with Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp leading the pack, according to the app companies annual reports collected by statistics company Statista. That number will reach about 3.6 billion or roughly half of humanity by 2018, according to tech consulting firm Activate.

But due to the very personal nature of messaging, media companies and brands are rightly nervous about interrupting the conversations. “Should brands insert themselves into one of the most personal activities online? Many apps, such as games, allow advertising, but who wants ads from Pampers cluttering their most intimate chats with friends?” wrote SiliconAngle editor in chief Robert D. Hof in the New York Times.

Many messaging services either don’t allow advertising or severely limit it for that very reason: not wanting to antagonise consumers.

“If we misstep with certain audiences, they’ll unplug,” Suzy Deering, chief marketing officer at eBay, told the New York Times.

“Nearly all the marketing in these apps remains experimental,” wrote Hof. “Because the apps vary in their user appeal and acceptance of ads, companies often have to create different campaigns for each app, a costly and time-consuming process. And they lack the tools to track results as well as they can with other forms of advertising.

“That doesn’t mean brands are completely unwelcome on messaging apps,” wrote Hof. “But it does mean that so far on these services, they are remarkably restrained in their approaches, focusing less on promotion and more on providing entertainment or utility — or both.”

That said, messaging platforms offer more ways to monetise than apps do. “Unlike apps, messaging platforms can push content — businesses will pay for the ability to push content (with opt-ins),” wrote Beerud Sheth, founder and CEO of bot-building platform Gupshup on the company blog. “Messaging platforms are already experimenting with sponsored messages (contextually). My guess is that the monetisation models will be closer to websites than apps.” The innovation team at Brazilian news outlet Correio came up with an idea reminiscent of the AOL Chat Rooms of the mid-90s. Correio thought they could at- tract a community and make money with chat groups built around lo- cal passions that would either be sponsored or have relevant ad messages discreetly inserted.

“I started thinking about how useful [Correio] could be if we started gathering people around their interests, whether that’s news about the city, economics or sports, and maybe even have our desks producing for WhatsApp groups,” Correio innovation editor Juan Torres told journalism.co.uk.

The first opportunity that presented itself was a big football match.

Torres and his team limited the number of attendees to 59 (they wanted to keep it small and they chose a number that matched the last year one of the teams had won the national cup). Despite a multi-step application process (applicants had to supply their name, email, phone number, neighbourhood, and favourite football team), the 59 spots were filled in just 30 minutes.

During the match, Torres inserted some videos and game analysis from Correio staff, but it was the members of the group who kept the conversation going by posting information about the players, game commentary, and relevant videos.

Torres and his staff left the group at the end of the match, but the members enjoyed them- selves so much that they decided to continue the group, renaming it Correio Bahia after one of the teams.

“People saw a lot of value in gathering around such an important issue for them, and they told us they hoped we would do the experiment again,” Torres said. “While one group is not scalable, how about if we ran hundreds of groups?” Torres wondered afterward. “Some of them could be permanent (for example, those with people from a neighbourhood or for economy and cultural issues, etc.) and some of them temporary (such as those for a specific event like a football game or the Oscars or a political debate, etc.). Wouldn’t that be scalable? Yes. Would people pay for it? We don’t know yet. Would that sustain the costs? We don’t know yet.”

The messaging platforms themselves are exploring monetisation. “We’re pioneering new advertising formats that are native to messaging,” Josh Jacobs, president of services at messaging service Kik, told Digiday. “We’ve found that AppNexus’ open platform is a great canvas for innovating in ways that fit into the existing advertising ecosystem but that also stand out by delivering the amped-up engagement opportunities that are unique to messaging.”

Ad agencies are getting into the act as well. Global ad agency Droga5 is employing new thinking to crack the puzzle of how to monetise without antagonising messaging app users. “Currently, the main opportunity is through things like campaign GIFs, stickers and bitmoji, but we expect brands are going to get far more integrated,” Tom Hyde, Droga5 social communications strategy director, told CampaignLive. com “Social profiles are becoming the new apps, and chat the primary interface.”

One reason advertisers have been slow to adapt to messaging is that the industry is lacking traditional IAB-style ad formats that dictate ad dimensions and file sizes for messaging apps, according to Cathy Boyle, an analyst with eMarketer.

“Messaging apps have unique ad formats — mostly ads that are native to their messaging environment — and because of that, advertisers can’t easily extend campaigns to include messaging apps without developing unique creative assets,” she told CampaignLive. “In addition, it’s hard to identify the right metrics to determine if the campaign has

been a success.”

If messaging apps are the hottest new thing, chatbots aren’t far behind.

Just as messaging apps snuck up on us, before we realise it, chatbots will become a dominant part of our lives. Smartphone owners already talk to Siri, Android owners talk to Google Now, Assistant, Cortana, Robin, Andy, Alice and others.

Owners of digital personal assistant gadgets like the Amazon Echo, Google Home, Cubic Robotics’ Cubic, and Chinese tech company Lenovo’s Smart Assistant ask the devices to read the news, play music, give them a recipe, etc.

Since Facebook launched its Messenger chat- bot platform in April 2016, more than 11,000 bots have been added to Messenger, according to Facebook vice president of messaging products David Marcus writing in a Facebook post.

Chatbots will become so ubiquitous they will be known as the “invisible apps”. “Chatbots are changing the ways users interact with the internet, creating an all-inclusive environment often within messaging apps,” wrote Raja Mitra, vice president at Singapore-based internet marketing firm Mgmt. Consultancy. “For example, while going on a trip, users will no longer have to download multiple apps to perform different activities. Typically, they should be able to book a flight, hail a cab and book a table at a restaurant all within one messaging platform. Put another way, chatbots have the potential to replace individual apps altogether. Messaging apps, together with their bots, will provide the environment for direct, instant and multi-pronged interactions with potential customers.”

OK, so chatbots are big and getting bigger.

“But how will these things make money” for media companies, asked Ross Simmonds, co-founder of lifestyle subscription service HustleAndGrind.com, writing on chatbotsmagazine.com.

“So far, subscription models seem to be the most viable in monetising chatbots,” wrote Ivan Cherevko, founder of Mr. Chatbot, in a Quora post. “Pana, for example, is a US$19/month travel chatbot. Still, connecting to an existing business model — ecommerce, SaaS [Software As A Service], affiliate [referring readers to another site and collecting a percentage of any resulting revenue] is the most straightforward way to monetise bot engagement — for example, an online shop that uses a chatbot to generate extra sales.” (Be sure to read our chapter on chatbots and messaging apps elsewhere in this book.)

MOBILE ADVERTISING

1. Native.

Native solves all the problems banners presented. Banners were a format designed for big desktop screens. What idiots thought they’d work on screens a fraction of that size? They didn’t, big time. Native eliminates the obstruction to the user experience on the mobile web or in a mobile app, providing a seamless integration with the mobile content. Native fits — both the device and the experience.

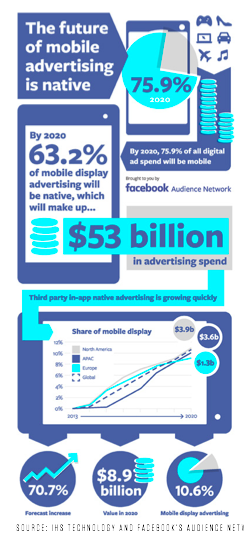

By 2020, 63.2 per cent of mobile display advertising will be native, which will make up US$53.4bn in advertising revenue, according to a 2016 IHS Technology “Future of Mobile Advertising” report.

More on native later in this story.

2. Data-driven programmatic

Programmatic has always been about data, but the difference between early programmatic days and today is the sophistication and precision of the data and our ability to analyse it in ways we never could before, all of which should push advertisers to double-down on programmatic. (See the section on Analytics in our “Tech” story.)

“The data/audience dimension is uniquely different with mobile vs. desktop,” Ian Karnell, GM of monetisation platforms at mobile service provider Phunware told MarketingLand. “As users go about their daily lives with their smartphones, they leave a digital trail that tells brands who they are, where they have been, their preferences, and where they will go next.

“Consider the contextual audience building and targeting opportunities that exist, programmatically, leveraging insights from a user’s digital trail,” said Karnell. “Although brands can’t personally match a device ID to an individual user, they can identify trends that can make an impact. (Device ID# 1234 attended the last five NFL home games, visits a bike shop 1x/month, and goes to Joe’s coffee on Thursday mornings.).”

3. Artificial intelligence

“Think [about] how often we consult these amazing ‘pocket-sized oracles’ for information,” wrote Aaron Strout, president of integrated marketing agency WCG, on MarketingLand. “Whether it’s for restaurant reviews, flight status, directions, weather or movie times, we as consumers are increasingly expecting smartphones to use the overwhelming amount of context they have to give us better answers.”

Given the combination of consumer need, sophisticated messaging apps/chatbots, and the ubiquity of smartphones, services like Facebook are starting to leverage the clues we provide (combined with their own data) and their own messaging app (Messenger) to do things like offer us Uber rides when we mention the service on Messenger.

“Imagine companies being able to insert offers and recommendations contextually as you’re group-chatting,” wrote Strout. “Obviously, the AI behind these opportunities needs to be smart (well beyond offering you a link to Uber when you mention the service), but this could and should be a game-changer if done correctly.”

We take a detailed look at the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) for media companies in our chapter on “Messaging Apps & Chatbots” in this book.

While we are waiting for agencies, advertisers and media companies to catch up with native, programmatic, and AI, the best answers for mobile advertising today have to be paid social advertising, in-app advertising, pre-roll video (and perhaps mid-roll with Facebook), and text messaging.

Paid social advertising

Depending on how much a consumer uses one of the social networks, paid social ad companies can know a tremendous amount about their behaviour, likes, dislikes, etc., enabling the rather precise targeting of advertising (presuming the user pays any attention to ads, versus the native appearance of “native”). Paid social campaigns can also be informed by a user’s behaviour on other channels outside the social network thanks to the extension of programmatic and CRM beyond email and web.

In-app native advertising

“First party in-app native, like those seen on Facebook, will continue to be the largest revenue driver,” according to the IHS report. “Third party in-app native will continue to grow, at an annual average rate of 70.7 per cent and will account for 10.6 per cent of all mobile display advertising at US$8.9bn by 2020.”

First party native advertising is advertising served within the media company’s proprietary app; third-party native advertising is served by a third party onto a publisher’s or app developer’s inventory. Third-party will be the fastest growing format in online advertising, according to the IHS report. “Other than paid social and native advertising, in-app ads are probably the most effective form of mobile advertising,” wrote Strout. “One of the main advantages is that marketers have more control over where ads show up in the experience and who the ads target, since they own the overall experience. The app makers also have a good amount of data (even if anonymised) on the users who are targeted based on their behaviour.”

Video mobile advertising

Digital video advertising is growing like crazy. In the US alone, it topped US$10b in 2016 and could nearly double by 2020 (an estimated US$18b), according to eMarketer.com. “This sustained growth makes video one of the brightest spots in the digital advertising market, but has also created several difficult problems that industry practitioners are working to solve: ad blocking, fraud, a profusion of low-quality inventory and increasingly ineffective use of TV-style advertising on digital platforms,” according to a January 2017 eMarketer.com report.

The report’s authors also recommended the following video advertising strategies and best practices:

- Include audience-based buying, refined targeting, advanced metrics, and the use of

third-party verification. - Personalisation, branding ads early and often, and matching ad formats to the many devices, platforms and content types available to marketers.

Text/SMS

That old war horse — text messaging — is still one of the most-used features on mobile devices. And from an advertiser’s point of view, texting is the most democratic advertising approach because texting works not only on smartphones but also on feature phones which are still prevalent in developing countries.

If anything, text messaging has gotten hotter. Messaging apps now have more combined users that the social platforms (Facebook, Twitter, etc.). Dozens of messaging apps like WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Telegram, Line, Viber, WeChat, Signal, Snapchat, etc. are commanding the time and attention of consumers.

“The one major thing to watch out for here [for advertisers] is that using this very personal channel comes with a higher level of responsibility,” wrote Stroud. “While marketers can gain a level of access similar to when users opt into email, the expected value from the end user is several times higher than it would be in areas like in-app, video or display.” In addition, the advertiser would be interrupting a very personal conversation. Unlike social media where conversations are often held publicly, messaging apps are between two people or a small group.

Progressive Web Apps

The ultimate answer for the future of mobile advertising may be Progressive Web Apps (PWA). A PWA functions like native apps but on the open web. Therefore, your content and advertising isn’t hidden behind an app’s walled garden and can be discovered and shared by everyone. That gives ads on a Progressive Web App a greater potential audience in addition to the subscribers to that app. (See our chapter on “Progressive v. native apps”.)

NATIVE ADVERTISING

Being hailed as the saviour of publishing was a heavy burden for native advertising to carry.

Too heavy, some would say.

Two separate studies in 2016 found that renewal rates for native advertising were either 33 per cent (a study by ad sales intelligence company Media Radar) or 40 per cent (a study by native ad tech company Polar).

That said, some media companies are succeeding quite handsomely with native, thank you very much. “The top native sellers win renewal rates between 60 per cent-80 per cent,” MediaRadar CEO Todd Krizelman told Real-Time Daily. “The Atlantic and QZ have consistently strong performance that out- strips so many.

“Strong performance will lift renewal rates for publishers who are consistently showing their advertisers results,” Krizelman said.

The advertising and media industries are still quite bullish about native advertising.

Native ads will drive 74 per cent of all ad revenue by 2021, according to Business Insider (BI). Their data further suggest that spending on native advertising in the United States, for example, will reach US$21 billion by 2018.

While the largest segment of native ad spending is in social media, the fastest growing segment is native-style display which is expected to grow by more than 200 per cent over the next two years, according to BI. And much of that growth will be in programmatic native aimed at mobile devices. “While banners with native elements and in-feed ads tend to dominate the programmatic native. A number of factors have driven interest in native, despite lingering confusion around the term [including] the successes of in-feed plat- forms like Facebook, concerns about ad blocking and the growing acknowledgement that desktop-driven formats like banners just don’t cut it on mobile,” said Fisher.

There are several well known media companies showing how native can be done right and very profitably.

One of the oldest native pioneers, Forbes, took a lot of flak initially.

In 2010, “our editorial model upset traditional journalists,” said Lewis Dvorkin writing on the company blog. “The marketer-as-content-creator idea really got them riled up. Today… nearly all ad departments have built programs for brands to create digital content. “Forbes’ BrandVoice, our industry-leading program for what’s now called native advertising, is booming,” Dvorkin wrote. “It helps account for 35 per cent of our digital revenues, which in turn make up 75 per cent of our total ad revenues. Forbes is continuing to push the boundaries with the anticipated 2017 launch of Brand360, a blending of multiple native advertising campaign elements across multiple platforms.

“It’s the next stage in marrying editorial and branded content across multiple platforms at the same time,” wrote DVorkin. “In the past few months, our designers have been hard at work mixing and matching print, video and digital editorial elements with related BrandVoice content, again with clear and transparent labelling. In today’s media universe, context, integration and packaging across print, desktop, video and mobile can help busy readers get what they need as they move from one device to another.”

Another pioneer of native was The Atlantic Group. In 2013, Atlantic was the poster child for everything that was wrong with native when it published an unedited advertorial posing as a native ad by the Church of Scientology extolling the church’s growth.

Just three years later, native advertising at The Atlantic for 2016 was projected to be 75 per cent of company’s ad revenue, up 15 per cent from 2015, Hayley Romer, senior vice president and publisher for The Atlantic, told Digiday.

The publication is offering a spectrum of native ads, from video to infographics to text- based editorial pieces. Last year, readers spent nearly seven minutes on its two best-performing advertorials: Qualcomm’s “The Space Within” and Boeing’s “A Century in the Sky,” compared to the average time spent of four to five minutes for its sponsored content. Atlantic Re:think, the in-house marketing group behind The Atlantic’s sponsored content, is now a team of 32 people, up 25 per cent from last year.

Condé Nast Britain, which has been producing native for years, only launched its own native team and studio in 2016. The centralised team has 18 people spread across commercial, creative and production, with more roles to be added in 2017.

The impact of the new team was immediate. Revenue from native accounted for 50 per cent of all digital revenue in 2016, up from 25 per cent in 2015.

British GQ, which launched a dedicated video channel on its site in February 2016, now has 30 per cent of the video content on that channel being commercially sponsored. Condé Nast Britain is unique in two ways: heavy use of data analysts on the native team and use of editorial staff to create the ads.

Much of the growth spurt in its native advertising revenue is due to the five data analysts on the team, Condé Nast group digital director Wil Harris told Digiday. The analysts work closely with clients to determine where and how to distribute and promote the content across platforms, Harris said.

Then there is a brash start-up making millions from native. Ryan Harwood launched a women’s lifestyle digital outlet called PowWow in 2010, and almost immediately started doing “native” before it was even a term.

“Our editors — not the business side — actually came up with the idea that we should try native advertising, about four years ago,” Harwood told Business Insider. “‘Let’s write content in our own voice, integrate it.’ Native wasn’t even a word yet.”

Today, native accounts for 85 per cent of the company’s revenue of US$10m in 2015, and an estimated US$20 in 2016. The PowWow editorial team writes the native content. “There is no [separate advertising] content studio” at PureWow, Harwood told BI. “[Our writers] know the voice.” And that is a large part of the reason PowWow’s native ads work so well, Harwood contends.

Meanwhile, one of the old warhorses of publishing, The Washington Post, may have come up with the best way to increase the effectiveness of native ads.

Creating great native content on one thing, something most media companies can do easily, but getting people to click on native ads is another challenge altogether. In February 2017, the Washington Post unveiled a new branded content ad format, called Post Cards. Post Cards takes a branded content campaign and breaks it down into its multimedia parts (sli

deshows, galleries, text, video), then it reassembles the parts and presents them to users based on their consumption history on the site, Jarrod Dicker, Post head of ad product and technology told Digiday.

Before, the Post would show the same native ad to everyone, Dicker said. Now, for example, a person with a history of being a heavy video watcher would likely be served a version of the ad that starts with video.

The more tailored native ads are to a reader’s consumption patterns, the more likely the reader is to engage with it, Dicker told Digiday.

And in what could be a real breakthrough in enabling engagement, Post Cards can be formatted to let people read or view the content in the unit without having to click through, acknowledging that it’s hard to get people to click on ads and that Google and Facebook have trained people to expect pages to load lightning fast, Dicker said. “This allows us to have zero latency,” said Dicker. “We’re limiting the click stream.”

NEWSLETTERS

Like text messaging, another old warhorse — the newsletter — is making a comeback.

But these are not your father’s old newsletters.

“What publishers are doing now is merely scratching the surface,” Dave Helmreich, the chief operating officer of email monetisation solutions company LiveIntent, told Digiday. “Email is no longer about sending email. It’s about the access it provides to identify and market to people in a mobile-first world.”

Email newsletters solve a lot of problems posed by other means of monetisation.

“Email is not in itself the answer, but is arguably the best channel for content distribution,” Keith Sibson, vice president, marketing at Post- Up, an email tool provider, told MediaPost. “It sidesteps ad blockers, and takes back control from platforms that try to own and sometimes subvert the audience relationship (e.g., Facebook). Email is the audience relationship that the publisher owns directly, and that publishers can reach at a time of their choosing.”

“We have clients who generate more than 60 per cent of their revenue directly or indirectly from email,” Sibson said. “You can sell ads within email, do dedicated promotional mailings, native ads within content, invite subscription signups, trigger micro-payments, and even charge for the email content itself. Email is more strategic than any one monetisation system.”

So, what are the business models for monetising newsletters?

Over two years of rebuilding the Financial Times, head of curated content at the FT Andrew Jack discovered ways to make money and then talked to editorial and sales colleagues around the world to pick their brains for a new report for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford.

He found that newsletters can deliver:

1. WEB TRAFFIC GENERATION CONVERSION: Readers clicking on links in newsletters boost web page views, enhancing two parts of a media company’s business model by potentially increasing subscriptions and advertising revenues. At the Washington Post, with more than 70 editorial newsletters, they are called the “drawbridge”, helping add “reach” and attract a wider group of readers and potential paying subscribers. Response rates from email newsletters are higher than social media, according to The New Yorker.

2. STANDALONE SUBSCRIPTIONS: Some media companies believe the content of their newsletter is so exquisite and unique that they can charge for it. For example, the Economist’s Espresso (and its associated app) and Brief.me in France have a fee for the email.

3. DONATIONS DIFFERENTIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: Some newsletters go out for free but periodically request donations. Others go out for free for individuals but are sold to corporations or commercial institutions.

4. ADD-ON TO SUBSCRIPTION PACKAGE: Some newsletters are used as enticements to get people to subscribe. For example, the Financial Times offers its Free Lunch, Brexit Briefing, and other specialist newsletters free of charge to standard or premium subscribers.

5. ADVERTISING: Many newsletters include banner ads, but an increasing number have native ads or sponsored content messages, such as Quartz’s Daily Brief, The Monocle Minute, and TTSO (Time to Sign Off) in France.

6. CROSS-SELLING: Some newsletters include a teaser to trigger clicks to a subscription paywall or directly to a subscription page. Some cross-sell with third-party commercial sites. For example, The Washington Post and BuzzFeed have partnered with Amazon. Some promote paid-for events.

7. BRAND AWARENESS: Newsletters raise awareness of the media company and its products and services.

8. COMMUNITY BUILDING: Niche newsletters can target particular passions and thereby develop deeper links to audiences in that community of shared interests, and gradually build a relation- ship, foster loyalty and, ultimately, offer membership and tickets to events.

PROGRAMMATIC

According to legend, the first banner ad appeared in 1994 on the website Hotwired, and it was so new and revolutionary that it had a 44 per cent click-through rate, according to Jeff Rajeck, a researcher at marketing firm Ecoconsultancy. The bloom came off that rose rather quickly and today banner ads achieve roughly a .06 per cent click-through rate, a drop of 99 per cent, according to Rajek.

Over the last two-plus decades since the Hotwired banner ad, media companies and advertisers have been desperately trying to find a marketing approach that attracts more consumer attention.

When it first appeared, programmatic advertising was definitely not seen as that answer. It was dismissively described as a dumping ground for the sale of unsold inventory at bar- gain-basement prices either to get scale (often on sketchy sites) or to prevent any ad spaces from going unsold. As recently as 2012, programmatic accounted for just 13 per cent of global display ad spend (US$5 billion), according to ZenithOptimaMedia “Programmatic Marketing Forecasts”.

A lot has changed since then.

Today media companies and advertisers have a vast treasure trove of data about their consumers’ interests and behaviours.

Because of that, programmatic can now serve as a laser-like precision tool to reach very refined audiences, even individuals, at scale. And, because of the value of that targeted audience, programmatic can now be sold at premium prices.

“While programmatic advertising has often been used to reach target audiences as cheaply as possible with little regard for the quality of the sites in which the ads appeared, it is now being used in conjunction with data segments to target individuals in intelligent and creative ways,” wrote Tobi Elkin, editor of MediaPost’s Real-Time Daily on the company blog. “Targeting helps identify people who are most likely to be receptive to a brand’s messages.”

Programmatic has been so successful at targeting that some predict 90 per cent of the ad market could be steered programmatically within one decade, according to media tech company OwnerIQ.

In 2016, programmatic in the US, for example, accounted for 63 per cent of display ad spending, and by 2020, programmatic could account for 85 per cent of targeted banners and 67 per cent of streaming video ads in the US, with the rest of the world not far behind, according to second-party data marketplace OwnerIQ.

“Programmatic trading is firmly in the mainstream, and is now the channel used for the majority of digital display platforms. Instead of simply using it for efficiency, brands are us- ing programmatic buying to target individuals creatively in premium environments,” Jonathan Barnard, head of forecasting for ZenithOptimedia, a unit of Publicis Media Groupe, told Real-Time Daily.

“The US is the largest programmatic ad market — valued at US$24.0 billion in 2016… followed by the UK, valued at US$3.3 billion, and China comes in third at US$2.6 billion,” Barnard said. “Programmatic trading accounts for 70 per cent of display advertising in the US and the UK, but just 23 per cent in China.”

Programmatic is so successful that it is growing faster than all other digital media channels, according to Zenith’s “Programmatic Marketing Forecasts”.

“Programmatic buying of digital media has become the norm in major markets, and is aggressively following this path in smaller markets,” Benoit Cacheux, global head of digital and innovation at Zenith, told MediaPost. “We believe that the growth of programmatic will continue to be fuelled by improvements in the quality of media available in programmatic environments, especially private market places, and the greater availability of programmatic mobile media, as well as the sophistication provided by ad tech solutions such as data management platforms and connected ad tech stacks.

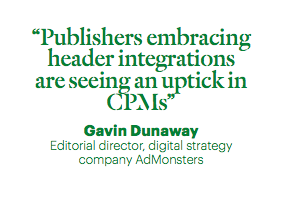

”One of the relatively new developments that has pushed programmatic ahead is header bidding. ”For the first time in a long time, I’m feeling generally positive about the digital advertising space — that mainly can be attributed to header integrations (e.g., header bidding),” wrote digital strategy company AdMonsters editorial director Gavin Dunaway on minonline.com.

“Google’s dominance of the publisher ad server business through DoubleClick For Publishers (DFP) forced media companies into embracing inefficient demand waterfalls,” wrote Dunaway. “DFP is for the most part a closed ecosystem, limiting the amount of publisher inventory demand sources could evaluate (particularly on a real-time basis). At one time this made sense, but no longer — which is why header integrations have upended the waterfall.”

With header integrations or header bidding, a media company’s advertisers get a look at all of the company’s inventory and audiences BEFORE they’re made available to everyone, enabling the advertiser to make smarter choices.

“Publishers can then better price their inventory and make private marketplace deals worthwhile for advertisers — they’re bringing context back into the equation,” wrote Dun- away. “The advertiser gets both the users they want and an environment they trust. And of course, contextual targeting can be leveraged for further granularity.