05 Nov The top six media technologies you need to know about

Walk, don’t run, to the future (but start walking now!)

What are you, some sort of troglodyte?

It’s 2018 and you STILL haven’t converted your entire editorial department into a virtual reality studio that also builds chatbots, creates audio pieces for those hot voice-activated personal assistants, and employs artificial intelligence software systems to write stories and social media posts?

Get with it!

Pardon the hyperbole, but to listen to some pundits, you would think we are about to witness the death of the smart phone, to be replaced by a new way of life with ubiquitous VR headsets, artificial intelligence driving editorial decisions, and having our content appear on smart refrigerator doors everywhere.

Some experts even forecast the imminent dominance of Zero Screen User Interfaces.

However, while they sounded breathless and often irrational, they were not entirely wrong.

On the one hand, in 2017 we saw what happens when media companies act rashly. The now-infamous “pivot to video” destroyed jobs and audiences at several high-profile media companies including Vocativ, Fox Sports, and Mic. Publishers that pivoted to video in 2017 experienced at least a 60% drop in traffic in August 2017 compared to August 2016, according to data from comScore. For example, Mic plummeted from 17.5 million visitors to 6.6 million visitors over that time period, according to comScore. Fox Sports lost 88% of its traffic. But Vocativ was the worst. The site virtually disappeared, dropping from 4 million visitors to 175,000 in July 2017. By August, comScore could not detect Vocativ’s traffic because it had shrunk so low. The calamity was made worse by the fact that Mic, Fox Sports, and Vocativ laid off dozens of editorial staffers to make the pivot.

In contrast to that carnage, 2017 also demonstrated the continued power of chatbots, the growing power of voice-activated personal assistants, and the growth of artificial intelligence across almost all areas of publishing, from marketing and editorial to sales and reader acquisition.

Virtual reality siren song

The siren song of media tech — virtual reality — continued to be high profile, but its use has been limited largely to big media companies, many of whose VR efforts have been underwritten by Google. No one is making money yet, and tech experts predict that widespread consumer access to affordable VR technology is years away.

“We likely remain 3-5 years away from the mass market consumer being able to go into a Best Buy [department store] and pick up a VR/AR headset for easy use… most users today remain early-adopters, largely gamers,” RBC Capital Analyst Mark Mahaney told MediaPost.

A subset of VR — 360 video — is more affordable to produce but lags in terms of attracting sponsors and advertisers (more on this later). Perhaps, however, we are looking at the media tech challenge the wrong way. Instead of focusing on the technology, some pundits say that we should be looking at consumer behavioural shifts instead.

“These shifts are behavioural shifts, not just technology shifts,” Ross Sleight, Chief Strategy Officer of UK-based accelerator Somo, told us at the FIPP World Congress in October 2017. “There’s never been a point where truly under- standing your customer was more important than it is today. Getting closer to customers is what drives start-ups’ business plans. They find a problem and then they solve it. I’m not sure that many publishers today think that way. If they stop thinking about technology and start thinking about the behavioural patterns of their customers, then opportunities will beckon upon them to build great new products.”

“These shifts are behavioural shifts, not just technology shifts,” Ross Sleight, Chief Strategy Officer of UK-based accelerator Somo, told us at the FIPP World Congress in October 2017. “There’s never been a point where truly under- standing your customer was more important than it is today. Getting closer to customers is what drives start-ups’ business plans. They find a problem and then they solve it. I’m not sure that many publishers today think that way. If they stop thinking about technology and start thinking about the behavioural patterns of their customers, then opportunities will beckon upon them to build great new products.”

Whatever we do, there is a lot at stake.

The right tech that delivers what readers are looking for on plat- forms they like and that fits with a publish- er’s existing tech stack can yield operational efficiencies, audience growth, cost savings, and above all, revenue, according to the authors of a Publish- ing Executive/NAPCO Research study. “The wrong technology can eat up valuable time, re- sources, and mental bandwidth,” wrote the authors. “Or worse, operating in an environment of thin margins, the wrong tech investments today can have strategy and financial implications that ripple for years.”

So let’s take a look at the media tech that has the most potential benefit for media companies looking to avoid getting left behind but wary of spending too much time and money on the next shiny new thing.

We have identified what we believe are technologies that will dramatically impact media companies in the short-, medium-, and/or long- term future:

1. Artificial Intelligence

2. Voice-Activated Personal Assistants 3. Chatbots

4. The Internet of Things (IoT)

5. Visual Search

6. Virtual Reality

1. Artificial Intelligence

If all the media tech out there, artificial intelligence (AI) is easily the least understood, but also fast becoming a ubiquitous and powerful presence in the lives of our consumers.

Many people interact with various forms of AI multiple times a day without realising it.

“When you use Facebook or Google or Apple, you’re using it,” Karim Sanjabi, Executive Director of cognitive solutions at media agency Crossmedia, told eMarketer. “It’s recommend- ing your picture, it’s reading your email, and giving you relevant ads back against that in Gmail. You probably interact with AI 30 or 40 times a day and may not know it.”

For the immediate future, the form of AI that holds the most potential for media is called “conversational computing”.

“Talking to machines, rather than typing on them, isn’t some temporary gimmick,” wrote Amy Webb, CEO of the Future Today Institute, for Nieman Reports (a Harvard-based journalism think tank). “Humans talking to machines — and eventually, machines talking to each other — represents the next major shift in our information ecosystem.

“Voice is the next big threat for journalism,” according to Webb. “Conversational computing is the next step to realising the great promise of AI, which isn’t a single technology, but rather a broad term for how computers use and learn from our data.”

“Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, IBM, Microsoft, and Baidu are engaged in an arms race for AI,” wrote Webb. And yet media execs “either don’t care or are allowing themselves to be distracted by the wrong tech trends. [They] are discounting the importance of voice or giving away their content for free across platforms like Amazon’s Alexa, this time in audio form.

“They aren’t modelling out how our information consumption habits will evolve once we’re all talking to the various machines in our lives,” she wrote. “Execs aren’t engaged in the sort of strategic thinking that will result in completely new business models to address what’s coming next.”

That is not entirely true.

Employing AI across all media departments

Not everyone is asleep at the wheel. In fact, several media companies are even doing much more than just modelling and thinking.

Media companies are beginning to employ AI across all departments, including editorial, marketing, sales, and reader acquisition.

For example, the Tech Hub team at Yoox Net- a-Porter has been using AI since 2015 and today is employing it to improve mobile capabilities like image recognition, natural language search, tailored search results based on a shopper’s size and location, personalised recommendations based off of purchase history, and virtual personal styling.

Here’s an AI example from the editorial side: While many media companies have eliminated comments because of the hassle of moderating them, The Washington Post and The New York Times are taking the opposite tack.

The Post started using AI to filter and moderate their one million comments a month. The Post’s engineering team built “ModBot” to filter new comments by referencing a record of deci- sions made by The Post’s human moderators over time. ModBot breaks comments down into their component parts and scores them against The Post’s discussion policy.

At the NYT, they, too, are using AI to separate toxic comments from healthy ones.

Using a machine learning technology from Jigsaw, the technology incubator that belongs to Google parent company Alphabet, the Times uses Jigsaw’s algorithmically-driven application called Perspective to filter comments.

This frees up the Times’ community editors to go from being able to offer comments on just 10% of stories to 25%, aiming for a goal of 80% of stories being open to comments.

Here’s another editorial example of AI at work:

In the UK, media company GiveMeSport is using AI to help writers stay abreast of developments in their field and write stories and social media posts with the greatest likelihood of resonating with their readers.

GiveMeSport uses a natural language processing tool developed by the site’s new owner, Breaking Data, to scan Twitter every second, reviewing relevant tweets based on predetermined keywords, like teams, players, clubs, leagues or stadiums. The tool filters, vets, and gathers the information into categories like “major event,” “related news” or “marquee news”. Finally, the tool sends the information in the form of an alert to journalists.

GiveMeSport embedded another AI tool in their content-management system which scores writers’ Facebook posts on a scale of 1-100 on its chances of high click-through rates or engagement (the tool can also spot and negatively score clickbait headlines and copy). The AI tool can assess how combinations of words, sentence structure and images will resonate with the tar- get audience. “Distribution is a science; we don’t want to leave this to chance,” Breaking Data CEO Nick Thain told Digiday.

Artificial intelligence and advertising

On the advertising side, AI is being used to deter- mine the what, where and when of ad campaigns. With those decisions increasingly being driven by data, and with the amount of data growing by leaps and bounds, no human being can possibly gather and analyse it all.

Enter AI.

“Every CMO I speak with knows that hu- man-driven personalisation doesn’t scale,” Allen Nance, Global CMO at marketing automation firm Emarsys, told eMarketer. “The human brain can no longer siphon through all the data and execute campaigns in real time to drive personalisation at scale. We’ve simply moved beyond the human capacity.

“Marketers should no longer be importing and exporting data, building segments or dragging and dropping,” Nance said. “The machine is not only better suited to decide the timing of specific messaging in real time and at scale, it is also better suited to decide what channel to message consumers on. The machine potentially knows which channel consumers are interact- ing with and can deliver a message to them in real time — no human, no build-a-campaign, no drag and drop. Instead of marketers spending 80% of their time on data, segmenting, dragging and dropping, etc., they can spend that time on strategy, content and creative.”

Artificial intelligence is also coming to play in the area of native advertising. At the Washington Post, they were running into the same problem every other publisher and marketer has encountered: the high cost of creating and distributing native advertising and the difficulty of getting it to scale.

To solve those problems, The Post created two AI tools (Own and Heliograf) to let brands import their own content and deliver it in a personalised fashion.

The Own tool serves ads to consumers based on their reading and viewing behaviours on the Post’s site, while Heliograf creates a personalised message. This delivers personalisation at scale relatively inexpensively compared with bespoke native ad or branded content campaigns. Brands that don’t want to pay for custom campaigns are attracted by the savings while still getting the targeted distribution they need.

The system is automated, which The Post claims results in 80-90% profit margins, not that far from the rates they get for display and pre-roll video. “Not only are margins extremely high, but this can be done in 24 hours turnaround time,” Post VP of Commercial Product and Innovation Jarrod Dicker told Digiday. “So this is solving for margins and managing turnaround times.”

AI must be human-to-machine-to-human

“One of the promises of AI is around the ability to create more personalised experiences for customers at every touch point, in context, at scale. But you can’t do that level of personalisation, at scale, human-to-human. It needs to be human-to- machine-to-human,” John Ellet, CEO of marketing consultancy nFusion, told MediaPost.

So, instead of machines replacing humans (as feared), humans must train intelligent machines so those machines can dynamically search, sort, craft, customise, and target editorial content and ad campaigns in real time for each and every editorial or advertising target in their physical location at the time. And soon, AI will be able to target an individual’s mood in real time.

2. Voice-activated personal assistants

If you have any doubts about the power of voice computing, you are already living in the past. Half of US respondents in a global survey already use their voice assistants on a weekly basis, with the rest of the world not that far behind at 31%, according to a June 2017 study of smartphone owners worldwide by J. Walter Thompson, The Innovation Group, and Mind-share Futures.

Looking to our future users, millennials make up the biggest group of voice-enabled digital assistants users, with 29.9 million using them at least once a month, according to the eMarketer Forecast on VR and AR Use. Voice searches will make up 50% of all searches worldwide by 2020, according to the eMarketer forecast.

Ambient computing reduces friction

“I think we’re at the early stages of what I’d call ambient computing — technology that reduces the ‘friction’ between what we want and actually getting it in terms of our digital activity,” Washington Post Senior Product Manager Joseph Price told The Nieman Lab, a US-based journal- ism research centre. “It will actually mean we’ll spend less time being distracted by technology, as it effectively recedes into the background as soon as we are finished with it. That’s the start- ing point for us when we think about what voice experiences will work for users in this space.”

One of the biggest advantages of voice enabled computing is the almost insignificant learning curve. Speaking is intuitive. After learning how to turn the device on and connect to the internet, it’s just like having a really, really smart friend in the room to talk to.

In mid-2017, the National Public Radio and Edison Research in the US conducted a study to find out what users are doing with these voice-activated devices. Music was unsurprisingly the top activity, but the second was to “ask questions without needing to type.” Another top activity was to get news and information — an encouraging result for media organisations.

“The frictionless way in which these devices enable audio consumption is already changing listening behaviours, and potentially increasing audio consumption overall,” Edison VP of Strategy Tom Webster told The Nieman Lab.

“Voice natives”

The millennials have been called “digital natives”, and now we’re going to be getting the “voice natives” who will be completely at ease engaging with technology verbally.

According to the NPR-Edison study, the most-used voice functions in terms of activities media companies can enhance are:

• Flash briefings

• Podcast streaming

• News quizzes

• Recipes and cooking aids

The primary drivers of the voice search phenomenon are smartphones and increasingly the voice-activated personal assistants: Amazon’s Alexa, Google’s Home and Assistant, Micro- soft’s Cortana, and Apple’s HomePod. The voice search commands — “Hey, Siri” or “Hey, Alexa” — are now well known by smartphone and digital assistant owners. In the case of Amazon alone (the market lead- er), the company sold an estimated 24.5 million voice-driven devices in 2017, up from 6.5 million in 2016, and just 1.7 million in 2015.

The primary drivers of the voice search phenomenon are smartphones and increasingly the voice-activated personal assistants: Amazon’s Alexa, Google’s Home and Assistant, Micro- soft’s Cortana, and Apple’s HomePod. The voice search commands — “Hey, Siri” or “Hey, Alexa” — are now well known by smartphone and digital assistant owners. In the case of Amazon alone (the market lead- er), the company sold an estimated 24.5 million voice-driven devices in 2017, up from 6.5 million in 2016, and just 1.7 million in 2015.

More than 100 Chinese voice-activated competitors

The verbal commuting phenomenon is not limited to western markets. In mid-summer 2017, Alibaba Group Holding Ltd announced the release of an Amazon Echo- like device. The two other Chinese internet giants — Tencent and Baidu — are also producing voice-activated assistants. And in a massive market like China, it’s no surprise that the big players won’t have the niche to themselves. More than 100 other Chinese companies have or will soon offer versions of the home bot, according to the South China Morning Post.

The floodgates opened almost three years ago when Amazon opened up their first voice-activated home assistant, Echo, to publishers and other developers to create content for it. Since then, some of the biggest names in publishing have developed “skills” for the Echo and other voice-activated assistants, including NPR, The Guardian, TechCrunch, The Washington Post, Harvard Business Review, and Slate.

A willing consumer base

UK research firm Mintel found that 62% of UK residents are comfortable controlling devices using voice commands. “We need to make it so these devices become more useful for sub- scribers,” Head of Financial Times Labs Chris Gathercole told Digiday. “Some people use us for entertainment, or to be informed, or when they are in research mode. We need to support all these different mindsets through voice controls. Passive listening is not the future.”

The Echo and its sister Amazon devices under the “Alexa” title boasted 25,000 skills at the end of 2017, up from 1,000 in June 2016.

Users apparently really like what they’re discovering with Alexa: “We have had 34,000 five-star reviews, a high level of engagement with average users interacting with Alexa 16 times a day,” EU head of Alexa Skills Max Amordeluso told us.

In May 2017, Amazon introduced the Echo Show — its first personal assistant with video (a seven-inch screen) — in the US. Some of the same first-adopter media companies jumped to create video content for it, including CNN, CNBC, Bloomberg, Scripps and Time Inc. Lat- er in the year, when the Show was released in the UK, the BBC, The Telegraph, The Evening Standard, and MTV began adding video content to their audio skills.

Be on every device the audience is

“We want to be on every device the audience is. Voice platforms are going to be huge,” Joanna Wells, Vice President of Digital Content for MTV UK, told Digiday.

The Telegraph, for example, hired a six-person editorial team just for Echo Show content. Every day, they choose five stories for video treatment which could include a mix of animation, video clips licensed from agencies, and videos created specifically for the bulletin. “We wouldn’t do that if it wasn’t going well,” Telegraph Chief Information Officer Chris Taylor told Digiday.

Media companies that do not produce much or any audio content face a choice: allow Alexa to read stories or do it themselves.

The first approach is easy to scale and low cost in terms of time and money. But various studies have found that listeners do not respond well to machine voices.

The second option is to have writers record the stories, or even re-write the pieces specifically for audio, incorporating effects that would not have been part of the text story. That approach is not as easy nor as inexpensive, but is almost certainly more effective.

The Financial Times has taken the quick and easy route. A four-person experimental team has been using a tool from Amazon called “Polly” to convert text stories to audio. It takes less than three seconds to convert a story to audio that is “read” by an artificial voice called “Amy”.

Some media companies are finding voice content and personal assistant delivery platforms to fit very neatly with their mission to reach audiences where they live today.

Buzzfeed is one good example.

Don’t reach for your phone, talk to Alexa

The edgy digital site wants its audience to develop a new habit: upon waking, instead of reaching for their phone and pressing multiple buttons to get read email, get notifications or RSS feeds or podcasts, all a user has to do is say, “Hey, Alexa, give me Buzzfeed!”

BuzzFeed titled their skill “Reporting to You”. It is usually a two- to four-minute audio roundup delivered by a different BuzzFeed reporter each day reading the most important news ranging from typical BuzzFeed topics like the latest dating mistakes to traditional news fare like the Korean nuclear crisis.

“We wanted to make something that stood out, sounded different and — most importantly — sounded human,” BuzzFeed Audio Director Eleanor Kagan told The Poynter Journalism Institute.

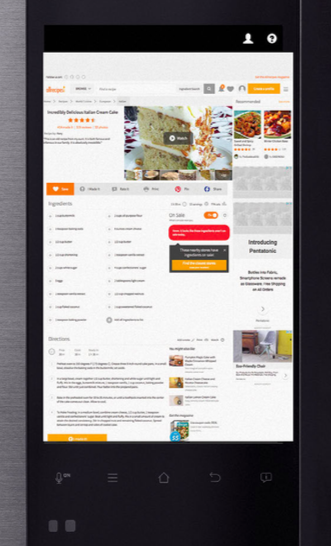

AllRecipes from Meredith is a poster child for early adoption of artificial intelligence. AllRecipes not only has a presence on smart refrigerators (more on that later), AllRecipes is also an Alexa skill.

Cooks with any Alexa device simply have to say, “Alexa, open the AllRecipes Skill.” Once in that skill, the chef can request specific recipes, ingredients or instructions and ask Alexa to re- peat or pause in the middle of reading the recipe.

Meredith’s research has found the use of its Alexa recipes skill peaks between 4 and 6pm and is most heavily used on Sundays. They also found that almost three-quarters of its Alexa Skill users say they anticipate not reading recipes in 20 years but relying solely on voice-activated devices.

To date, media companies say working with Amazon has been a positive experience. Amazon has a team of business developers, engineers, and “skill” developers to assist publishers’ teams develop content for their voice-enabled assistants.

“In general, they’re a really good partner,” CNN VP of Digital Products Rohit Agarwal told Digiday. “We get a lot of early insight and access to their product road map. They’re very responsive [and] flexible. They not only take the feedback, but they learn from us. It’s a bi -directional flow.”

Amazon allows monetisation without a cut

So far, Amazon also makes the arrangement potentially lucrative (once the business model is clear). Amazon allows media companies to monetise their Echo skills and does not insist on a revenue share, unlike other platforms.

“When we talk about how we’re going to monetise, we don’t get any pushback,” Agarwal said. “That would lead one to believe we’re in alignment. Also, they’re selling devices. If the primary purpose is that, then the content is what enables it to be attractive. It’s possible that where we make our money is in different places.” Despite the accolades, Amazon is not making monetisation frictionless.

In May 2017, Amazon banned interactivity in advertising in Alexa Skills unless the ads were delivered in Flash Briefings (news), streaming music, or radio skills. The rules limited third-party promotions and, thus, publishers’ ability to include sponsored content into any non-news Alexa Skills.

So, monetisation is a big problem for publishers like Hearst’s Good Housekeeping and Elle whose Alexa Skills don’t qualify as news.

Rules for approaching voice- activated devices

In considering the development of a “skill” for a voice-activated device, media veteran Peter Houston recommended following rules in a post on Publishing Executive:

-

- Avoid complicated skills development; opt for simpler “flash briefing” content

- Don’t think of voice as a platform. Think of it as just the latest content command and control system — from keyboard, to mouse, to touch screen, to voice interface. Just one more way for your audience to activate your content

- Don’t expect any revenue any time soon. The most likely scenario for publishers is 10-second pre-roll style sponsor messages like those being trialled by VoiceLabs

.

Once you dive in, there are some lessons from media companies that have already been there and learned things the hard way. Producers at the daily Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch select high-interest stories and boil them down to four or five sentences for the text-to- audio briefings.

“Out of the gate, no additional staffing was needed, because we are using automated feeds for Alexa to read,” Karina Pagano, Director of Digital Products at Dispatch parent company GateHouse Media, told the Reynolds Journal- ism Institute at the University of Missouri. “However, we do want larger [newspaper] sites to curate and perhaps rewrite tops of articles to fit the platform. Ultimately, we could see some newsrooms producing audio files. These two phases would take

For the most basic Alexa skill, the Dispatch used existing staff, adding the Alexa feed to their other responsibilities. “We have a team of eight producers who have primary responsibility for updating the website, sending out newsletters, editing videos, doing podcasts and other tasks that don’t affect the printed pa- per,” Dispatch Managing Editor for Digital Gary Kiefer told the Institute. “We’ve just made this one of the assignments. Typically, the person who is going to pick the stories for the news- letter that day will also handle the Alexa feed.”

“Part of helping audiences have a better listening experience includes making sure the stories are being read clearly,” said Keifer. “For example, Dispatch staff are discovering which words are hardest for Alexa to pronounce. Using a phonetic spelling often helps alleviate this.”

The hurdles facing voice-activated devices

The authors of the NPR-Edison study identified five hurdles standing in the way of success for voice-activated devices:

- Discoverability

- Navigation

- Data analytics/insights

- Monetisation

- Having a “sound” for your brand

Discoverability: The biggest concern is how do users find the content, either as a skill or app? When a user sets up a smart device, preferences are set through a mobile app, including prioritising the content sources you desire. “How would you remember how to come back to it?” asked Quartz App Product Manager John Keefe. “There are no screens to show you how to navigate back, and there are no standard voice commands that have emerged to make that process easier to remember.”

Navigation: “Web pages, for example, all have back buttons and they do searches,” Microsoft Research AI Vice President Lili Cheng told Wired. “Conversational apps need

those same primitives. You need to be like, ‘Okay, what are the five things that I can always do predictably?’ These understood rules are just starting to be determined.”

Data analytics/insight: A Nieman study by BBC Digital Launch Editor Trushar Barot found that media companies creating content for these devices all complain that “We don’t have enough data about what we’re doing and we don’t know enough about our users.” Amazon and Google provide some data but it’s not sufficient to substantiate key performance indicators. Nor are media companies certain exactly what to mea- sure. “What, for example, is a good engagement rate — the length of time someone talks to these devices?” asked Barot.

“The number of times they use the particular skill/app?”

Another set of data points made possible by these smart devices would be context. “These devices will have the ability to detect a person’s situation as well as their state of mind at a particular time, enabling them to determine how they interact with the person at that moment,” Associated Press Media Strategist Francesco Marconi told Barot. “Is the person in an Uber on the way to work? Are they chilling out on the couch at home or are they with family? These are all new types of data points that we will need to start thinking about when tagging our content for distribution in new platforms.”

Monetisation: As mentioned earlier, monetisa- tion is still a challenge, especially with Amazon’s limitations. One approach could be to use the devices to drive referrals and subscriptions.

But Barot had another idea. “A more effective way of looking at this would be through the experience of radio,” he suggested. “Internal research commissioned by some radio broadcasters that I’ve seen suggests users of smart speakers have a very high recall rate of hearing adverts while listening to radio being streamed on these devices. As many people are used to hearing ads in this way, it could mean they will have a higher tolerance level to such ads via smart speakers compared to pop-up ads on websites.”

Barot offered yet another idea: “Another revenue possibility is if smart speakers — particularly Amazon’s at this stage — are hardwired into shopping accounts. Any action a user takes that leads to a purchase after hearing a broadcast or interacting with a voice assistant could lead to additional revenue streams.”

A “sound” for your brand: Getting into the voice-activated device niche is quick and easy if you let the device convert your content to audio. However, that means your content sounds just like everyone else’s content. The most noticeable thing about the experience — the sound — is the same from brand to brand. “If you get the news from Alexa, you get it in Alexa’s voice and not in The Washington Post’s voice or Fox News’ voice.” Judith Donath from Harvard’s Berkman Centre for the Internet told an audience at an AI event at the Tow Centre for Journalism in New York. Listeners could easily lose the ability to distinguish from different content sources. Creating the brand “voice” would mean choosing the right narrators with the right tone and sticking with them, not an easily scaled or inexpensive thing to do.

3. Chatbots

Messaging app usage is in the stratosphere. The consumer appetite for

messaging apps three years ago propelled the top four messaging apps past the top four social media platforms in terms of traffic. Since then, the growth has continued.

But due to the closed and private nature of messaging apps, media companies have focused instead on their close cousin — chatbots — which can be standalone or integrated into messaging apps.

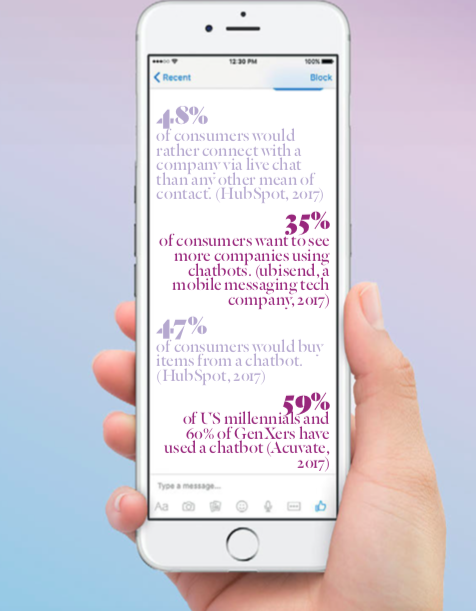

The consumer appetite for chat- bots has also been growing, albeit not as rapidly. That said, consider the following chatbot statistics:

• 38% of consumers had a positive perception of chatbots in a 2017 survey of 5,000 consumers from six countries by American marketing and analytics company LivePerson. Only 11% had a negative impression; the rest were neutral.

• 48% of consumers would rather connect with a company via live chat than any other mean of con- tact. (HubSpot, 2017)

• 35% of consumers want to see more companies using chatbots. (ubisend, a mobile messaging tech company, 2017)

• 47% of consumers would buy items from a chatbot. (HubSpot, 2017)

• In Nov. 2017, there were already 100,000 chatbots on Facebook Messenger alone — up from just 34,000 a year earlier (Acuvate, a chatbot company, 2017)

• 59% of US millennials and 60% of GenXers have used a chatbot (Acuvate, 2017)

• Chatbots have a higher retention rate than the top-performing apps in the US (Acuvate, 2017)

• By 2020, the average adult will have more conversations with a chatbot than with his or her spouse (Acuvate, 2017)

OK, maybe that last statistic is a bit over the top, but you get the picture.

Failures and hiccups

As with any new technology, there have been hiccups and failures.

Last spring, Facebook admitted a 70% failure rate with its chatbots, meaning that they could only handle 30% of user requests without human intervention.

Some of the difficulty with chat- bots revolves around the nature of the basic chatbot: They are hard to find, they require opting in (which then requires a new behaviour), they are pre-programmed and can only answer questions that have been included in their repertoire, and they are just not as personalised or as smart as they ultimately will be. But some consumers don’t understand the limitations and get frustrated when the bot can’t answer what seems to be a simple question (because it hasn’t been programmed to do so).

Smart bots that learn from every interaction are much more expensive to create and are thus far less common.

Also, some early adopters opted out. Mobile shopping start-up Spring discontinued its Facebook Messenger claiming it was difficult to use and lacked the personalisation they had hoped to gain. Fashion retailer Everlane also discontinued their Messenger chatbot, opting to stick with email.

Nonetheless, industry observers still envision robust chatbot growth.

“Chatbots that are developed for integration with messaging applications are expected to witness significant market demand in future,” according to a report from US-based market research company Grand View Research. “Chatbots are segmented based on types into stand- alone, web-based, or messenger-based/third party. The standalone segment is expected to hold the largest market share over the forecast period [2020]: Bots for service, bots for social media, bots for payments/order processing, bots for marketing, and others. The bots for social media segment held a significant share in terms of number of bots. However, in terms of revenue, the bots for service segment captured the majority of the market share.”

You can build a chatbot pretty easily

One development that will aid the growth of chatbots is the increasing ease of building one. “You can build these things — and actually now there are a lot of tools – you can build them pretty easily,” Joey Marburger, the Washington Post’s Director of Product, wrote for the Nieman Report. “Amazon has a tool called Lex, which [is] point-and-click, you can build a pretty robust bot without any code.

“So the future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed,” Marburger wrote. “And I think this is super true for bots. Bots aren’t totally new — they’re just getting more accessible. It’s demand in future” Grand View Research almost becoming a household name.”

And, for a change, media companies are actually hopping on these new platforms in the early stages in increasing numbers with increasingly imaginative approaches.

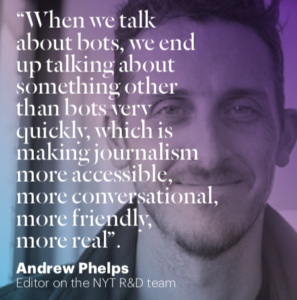

At The New York Times, they created a Facebook Messenger app in 2016 called NYT Politics Bot for Nick Confessore, a politics reporter covering the Trump campaign. “The idea was to combine the intimacy and charm of a human with the utility of a bot,” wrote Andrew Phelps, an editor on The Times newsroom R&D team.

People feel a personal connection with the bot

“So on the human side, Nick would actually script conversations every morning, choose- your-own-adventure style — and this is the important part — that reflected his point of view about the campaign from his unique vantage point. This wasn’t the voice of The New York Times. This wasn’t a quote-unquote ‘objective’ experience.

“And people really, really reacted — they really liked this experience,” Phelps wrote. “We got a quarter of a million people to have some sort of an interaction with Nick that they thought was personal and sort of unique to them.”

In early 2017, British Vogue launched Vogue Fashion Update, the first Facebook Messenger bot that allowed users to personalise their fashion news.

Launching for London Fashion Week 2017, Vogue Fashion Update helped users catch up on the latest shows, follow their favourite designers, and get all the latest news sent directly to their device via the Facebook Messenger app. Users could choose between getting British Vogue’s top stories daily, with up-to-date runway news during the international fashion week season, or opt for more tailored content based on the user’s chosen designers of interest.

Launching for London Fashion Week 2017, Vogue Fashion Update helped users catch up on the latest shows, follow their favourite designers, and get all the latest news sent directly to their device via the Facebook Messenger app. Users could choose between getting British Vogue’s top stories daily, with up-to-date runway news during the international fashion week season, or opt for more tailored content based on the user’s chosen designers of interest.

Chatbots increase interactions & subscriptions

And at the Harvard Business Review (HBR), the team used a chatbot to increase engagement and subscriptions.

“Our focus has been on how we increase the number of people having very regular, frequent interactions with HBR content,” Senior Editor Walt Frick told us. “We know that that’s one of the biggest predictors of getting people to subscribe, and so we thought a lot about what are the daily, or at least, weekly interactions people could have with HBR content that might introduce them to the brand, and potentially get them to subscribe.

“We think these are really great opportunities for people to have regular interaction with our content,” Frick said. “And, it’s an intimate interaction in the sense that you get a mobile notification when we send you a message and you’re interacting with us in a channel that you would otherwise be messaging with friends.

“The overall hope is you sign up and every morning you’ll get the latest articles from HBR

sent to you in that chat channel, with a notification on your phone,” Frick told us.

“Our first step has been: Let’s go to these chat platforms we know people are already using, where we know there are significant audiences, including people who interact with us in other ways, and let’s do what we already know how to do very well, which is take high-quality content and share it with those audiences in ways they find interesting and compelling,” Frick said.

If the HBR’s first chatbot experiment in 2016 on Slack is any indication (they acquired 10,000 subscribers to the bot), the new Messenger bot should be a hit.

And in the autumn of 2017, The Times of India launched a chatbot as a virtual personal assistant service to enable their users to set reminders, book cabs, recharge their mobile, book flights, do web check-ins, and make to-do lists among other things. The Times secured the soft drink brand Sprite as the exclusive brand partner for the launch.

Don’t build a chatbot just to have one

The danger of chatbots is the same as the risk with any new technology: Blind adoption. You shouldn’t do a chatbot just to say you have one. You must determine if your consumers have a need that you can solve with a chatbot. And then determine if it’s the kind of need that can be solved by bot technology as it exists today. If it’s a simple need with simple answers, a basic chatbot might work.

Or, if you have the talent and time to create a more interactive, more journalistic bot like the NYT, then go for it.

“When we talk about bots, we end up talking about something other than bots very quickly, which is making journalism more accessible, more conversational, more friendly, more real,” wrote the NYT’s Phelps. “The most common feedback that’s caught my eye is people write us to say Michael feels like a friend. You know — ‘this feels personal for me.’

“The point I want to drive home is that I’m not worried about this technology driving the humanity out of journalism,” wrote Phelps. “I’m really excited about the promise of technology bringing more humanity to journalism and creating more one-to-one experiences with more people that otherwise might not have been possible.”

4. Internet of Things

Every time you turn around, it seems there’s a new gadget that could be a place to serve up our content. That’s not just your imagination.

At the end of 2017, there were 8.4 billion IoT devices in the world — more than one for every human — according to Gartner Research. That number is expected to more than double to 20.4 billion by 2020, according to Gartner. Those connected devices include smart voice-activated personal assistants, smart TVs, smart refrigerators, and smart au- tomobiles, among other things.

The Internet of Things is all about “smart devices” on the one hand, running off of a variety of platforms – IoT – that allows them to connect and generate data (and loads of it) and artificial intelligence for the management of and execution on that data. Smart devices are in the foreground (consumer-facing), while the IoT and data (the prize) are in the background

The Internet of Things is a constant source of possibilities for the media.

Take the smart refrigerator.

Here’s how Samsung describes its top-of-the-line smart fridge: “The Samsung Family Hub Refrigerator allows you to connect with and entertain your family unlike ever before. With the wi-fi enabled touchscreen, you can leave notes/reminders and show off photos. In addition, with built-in Bluetooth speakers and Pandora, you can play your favourite tunes! It contains three built-in cameras that enable you to see what you have in your fridge from wherever you are through your phone.”

Smart tech opens unprecedented possibilities

To stay relevant and essential in our consumers’ lives, our content distribution channels must grow with our consumers’ growing number of new digital tools through which we can send them our useful and/or entertaining information. Those IoT devices represent “interactions between humans and machines that unlock possibilities,” according to an Ernst & Young study of media companies. Among other things, the study highlighted content personalisation, content discovery, recommendations, and gesture-based commerce.

“Being able to meet readers where they are is an obvious priority for the business, and while it can create unique challenges to support the ever -growing number of devices, the payoff is that doing so gives us a 360-degree view of readers’ habits and preferences — and that in turn allows us to build better content experiences for our customers, which fosters brand loyalty,” Rodale VP/Head of Digital Heidi Cho told Publishing Executive.

Some media companies are already there. If you were to buy the aforementioned Samsung Family Hub refrigerator, you’d discover recipes from Meredith’s AllRecipes. Using the fridge’s interior cameras, the system takes a visual inventory of ingredients and delivers an AllRecipes recipe.

“There are a lot of points or hubs in the kitch- en where we believe we can play a role,” Stan Pavlovsky, President of Meredith Digital, told Publishing Executive. “Our strategy around the Internet of Things is to enable our users in a very useful way, but also make sure whatever bets we’re making will scale with our business.”

Monetisation is not on the horizon

Monetisation of the IoT is still evolving. Meredith, for example, does not have advertisers on the refrigerator yet. Possibilities might include kitchen utensil makers, grocery stores, specialty ingredient makers, wine purveyors, etc. Think ecommerce.

The beauty of the IoT is that it presents unprecedented personalisation possibilities: super-targeted marketing to a single person engaged in a specific activity in real time. Given the situations, new revenue opportunities present themselves.

“My advice to other publishers is you have to focus on the consumer experience when you’re making your bets around innovation and where to innovate,” said Meredith’s Pavlovsky. “You can’t do it all, so be really smart about how and where. We know there are going to be connected devices that we decide don’t make sense for us and that’s okay.”

5. Visual Search

OK, so hardly anyone pointed their smartphones at those QR codes to get more information about a product or place or anything else those funny little boxes appeared on. Too much trouble. And they didn’t work most of the time.

But if you could just point your smartphone at an object and instantly get all sorts of information, well, that’s a whole different proposition.

Initially, the problem was ease of use. “You have to go to an app, open it… not a great custom- er experience,” Somo’s Ross Sleight told FIPP. com. “[But] once it’s built into the mobile phone camera and operating system (rather than being a separate app), suddenly you have the whole world available to augment.

It will be “point-and-learn”

“That’s terribly exciting, because being able to point a phone at Buckingham Palace and get in- formation about that; pointing it at someone’s car and getting information about that, or a pair of shoes and getting information about that, and buying it… Suddenly the filter to our world be- comes completely different,” he said. “We’re getting to a position where this is going to be a long-term reality, maybe not this year or the next, but soon,” Sleight concluded.

As cool as that possibility is, the big question for media companies is: “What’s the role for publishers in a world of [that type of] AR? Do they even have a role? My concern is they certainly do not have the technology or wherewithal (to make it work),” Sleight told us.

“I mean; if you are a fashion magazine, chances are you are not spending your time today worrying about visual search,” he said. “And if you have done AR, you probably said ‘let’s augment a page’.”

That kind of old “innovation” doesn’t cut it today. Now media executives must deeply question the role of their brand in this new connected world.

For example, if “a user uses a camera to search for a suit, the job of the fashion magazine should be to curate similar suits (for the user),” said Sleight. “But that’s what Google and ecommerce brands are already doing today.”

The gaping gap in visual search But Google and ecommerce brands don’t go far enough, delivering a bewildering list of single articles forcing the consumer to sift through them, sorting the wheat from the chaff, to reach an informed conclusion. No easy task, especially if that consumer is on the go — in a store or on the street looking for information quickly and easily.

Cue the niche media company!

In the case of a fashion magazine, the editorial department probably already has comparative reviews of the shoes or shirts or accessories or whatever the consumer is pointing his or her smartphone at. The attractiveness of this solution to the consumer is that the information is coming from a respected, trustworthy, familiar source: the magazine.

And yet, while this opportunity seems like a no-brainer, Sleight is worried.

“I am afraid publishers are getting further and further away from consumers, because they are not thinking about really solving their problems anymore,” unlike various startups out there that do exactly that.

There is still time for niche media companies to claim their spot in visual search. “Ecommerce businesses are good at things like recommendations, transactions, logistics and customer service elements, but have not yet fully cracked the early part of the customer journey — the why would I want the item in the first place? That’s where publishers currently sit — in the inspiration category,” said Sleight.

So niche publishers are still in a position of strength to be able to take advantage of this business and editorial gap in the coming visual search world.

But the gap won’t be there for long. “They (publishers) can very quickly lose this opportunity because other players are eating away at it, inserting themselves between the publisher and its audience (to deliver on all elements in the customer journey, including inspiration),” concluded Sleight.

6. Virtual Reality

I know I made fun of virtual reality in the beginning of this piece, but VR really is cool and could — some day — be a powerful tool for us in reaching out to inform and entertain our audiences, not to mention serve our advertisers.

But not today.

How’s this for a searing analysis: “In my opinion, no technology has promised more, delivered less, and destroyed more wealth than virtual reality,” said Stephen Masiclat, Director of the New Media Management programme at Syracuse University in New York, in an inter- view with Publishing Executive. “Really you don’t want to spend the money doing VR. You want the Aston Martins that are making the super cars to make the VR presentation. You’re just going to deliver the audience.”

One of the problems is that VR is an immersive, individual experience — you “leave” the real world on your own — whereas AR can and will happen in the real world.

The criticism, high costs, limited audience, and lack of advertising base have not discouraged some publishers from forging ahead or VR advocates from pushing for experimentation and adoption.

To wait risks being left behind

“[Media executives] are trying to protect where they are making money today, and yes, they are making money there, but they will be ill-prepared for tumultuous change to come,” Ross Sleight, Chief Strategy Officer at Somo, said in an inter- view with FIPP.com.

“I speak to lots of publishers, and my concern is they are not thinking in that way,” he said. “They’re not thinking like a Google, they’re not thinking about how to disrupt themselves.

“The biggest threat to publishers is a belief they can sit back now, and just port what they’re doing onto another medium when the time comes,” Sleight told us. “By that time (when they realise that porting does not work), the relationship with the customer will be gone.”

For media companies, Sleight believes “VR is already relevant today” and presents an interesting proposition. “VR allows providing long-form narrative content in very different and immersive ways,” he said.

The willingness to invest in acquisitions and/ or organic experimentation in VR is crucial, according to Sleight. “Axel Springer has invested in [VR production company] Jaunt, The New York Times is putting increasing amounts of money behind this, and in the UK The Guardian is doing great work here… publishers are exploring this, trying to work out how these very immersive stories will happen.”

The NYT produces a VR film monthly

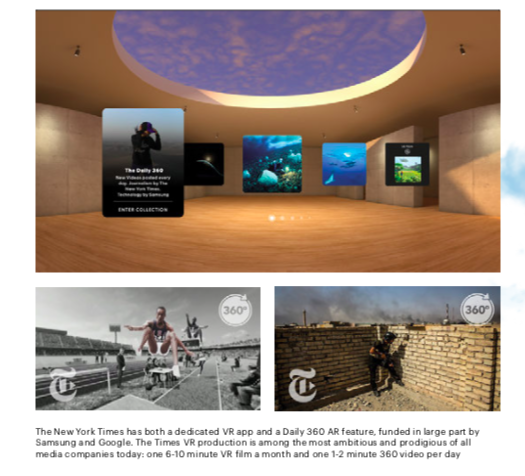

The New York Times has both a dedicated VR app and a Daily 360 AR feature, funded in large part by Samsung and Google. The Times VR production is among the most ambitious and prodigious of all media companies today: one 6-10 minute VR film a month and one 1-2 minute 360 video per day.

In October 2017, The Guardian, which began doing VR projects almost two years ago, gave away 97,000 Google Cardboard headsets to UK readers with select copies of the Guardian and via theguardian.com. The Guardian VR app is available for free download from Google Play or the iTunes store.

With the app, users can access the nine VR projects the Guardian has created.

But the Guardian’s VR experience, while exciting and extremely high quality, also serves to illustrate the monumental barriers to entry for most publishers. The company’s most recent VR offering took their five-person VR team six months to create. As shocking and costly as that was, it represented a 33% improvement over the nine months it took to create their first VR project.

Over at The Economist, their team produced three VR films in 2016 but VR projects in the future will only be produced with outside funding. “Would we make VR films on our own dollar? We don’t have any plans to do that,” Economist Films Director of Programs David Alter told Digiday.

Slate offers a VR show featuring avatars

At Slate, they launched a weekly Facebook Live show in virtual reality with actors and celebrities appearing in a virtual world via avatars created to look like the human participants. Slate is using a technology Facebook introduced in early 2017 called Spaces which enables up to three people to meet via avatars in virtual reality. The participants could watch videos together, play in 3D spaces, and more.

Applying Spaces VR technology to the Slate show “creates a kind of intimacy that feels very different from a video call,” Slate Editor in Chief Julia Turner told Variety. “It feels like you are in a new space together.”

Nonetheless, those case studies and others like them are outliers. “VR will not reach mass adoption in the foreseeable future,” accord- ing to the eMarketer Forecast on AR and VR in mid-2017. Mass adoption still faces serious hurdles. VR and AR headsets require a lot of computing power, and VR is so immersive it can cause motion sickness if the device doesn’t track exterior environments correctly. Advertisers also face both the hurdle of high costs and small audiences.

Augmented reality is easier, cheaper, quicker

Some media companies are taking the path of least resistance: Augmented reality (AR). AR is the opposite of VR in so many ways: It is far less expensive to produce, everyone has the equipment to view it, it is easier to scale, and advertisers are interested.

Numbers reinforce the point. In 2017, 40.0 million people in the US engaged with some form

of augmented reality at least monthly, up 30.2% over 2016, according to the eMarketer forecast. By contrast, 22.4 million people in the US en- gaged with a form of VR at least monthly, up 109.5% over 2016, according to the eMarketer forecast.

At the Washington Post, on the other hand, Marburger and his team are pushing AR.

“The [AR] tech has gotten a little better with these frameworks being available, lighter as- sets, things like that,” Marburger told Digiday. “Everyone’s got an AR-capable device in their pocket. There’s potential scale there.”

The Post created a team of two editorial people, two engineers, and a product manager to explore new forms of storytelling, including AR. “We haven’t bet the farm on it [AR], but we want to learn from it,” Marburger said. “Worst case, we come out of it better storytellers.”

So, where is all this media tech taking us?

Certainly to a world where information is more ubiquitous and more easily obtained at almost any time or place. And that’s a good thing, both for our society and for our media businesses.

But what’s coming next is not as easy to see as a good thing right off the bat: Brain-to -computer connections.

Businessman, engineer and inventor Elon Musk created a company in 2017, NeuraLink, that would build computers into our brains using a “neural lace” that involves implanting electrodes in your brain to upload or download information from a computer.

He’s not alone. As if Facebook wasn’t already too deeply embedded in our lives, the social media company is also experimenting with brain-computer interface technology.

That certainly makes “Hey, Alexa” seem pretty harmless and non-invasive, right?

So, in 2018 we’re not going to see the death of the smartphone or bump into people on the sidewalk because they’re all wearing VR headsets or all talking to our refrigerators.

But we’d better start getting ready for that day.