27 Apr You probably think digital ad fraud doesn’t affect you. Think again.

Your publishing company is almost certainly the victim of digital advertising fraud. Worse, your company may also, unwittingly, be an actual perpetrator or enabler of digital ad fraud.

Worse still, your very own personal computer could be defrauding other publishing companies, advertisers, and even your very own company. Right now. And all this fraud is costing you a lot of money and a lot of credibility, both directly and indirectly.

One consolation? You’re far from alone. Digital ad fraud affects between 10 and 60 per cent of different types of digital advertising, according to a variety of studies conducted in 2014.

Another consolation: There are a growing number of fraud-fighting companies dedicated to building innovative tools and practices to catch and, better yet, prevent and eliminate digital ad fraud.

Ad fraud costs $4.5m USD every hour

There is no time to waste.

This year alone, digital ad fraud will cost publishers and advertisers US$6.3billion (yes, that’s billion with a “b”) or US$4.5 million every hour, according to a landmark December 2014 study by the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) and digital security firm WhiteOps.

The 2014 study monitored 181 ad campaigns of 36 ANA member companies over 60 days and discovered hundreds of millions of bots infecting the advertising of big-name brands including Anheuser-Busch, Ford, Verizon, and Pfizer and costing the affected companies millions of dollars in wasted ad spending. The study analysed more than 5.5 billion impressions on 3 million domains.

No more turning blind eyes

Until recently, digital ad fraud was reluctantly accepted as an unfortunate cost of doing business. But that was before the fraudsters ramped up their game and started taking billions of dollars out of the digital advertising ecosystem.

“We have long suspected and have long known there was fraud in our industry,” ANA president and CEO Bob Liodice said. “We didn’t know the exact amount or the reasons why it was happening.”

Now do we. And it’s not a pretty picture. Here are just two examples:

1.One well-known British company was defrauded of US$488,000 when its $10,000/ day 2013 video ad campaign to sell big-name household brands on reputable US publishing sites was instead spent on Asian porn sites, according to BusinessInsider.

2. A well-known lifestyle publisher ended up serving 98 per cent of an automobile advertiser’s video ads to bots. “Out of almost 4,000 total video impressions from the placement, fewer than 100 were served to humans,” the report stated. The other 98 per cent were triggered and “viewed” by “bots” or networks of computers infected by software fraudsters can place in PCs through a variety of seemingly innocent means.

Ad fraud is alarmingly ubiquitous

The breadth, depth, sophistication, and outrageous cost of digital ad fraud was laid bare by the ANA/WhiteOps study:

“We have reached a crisis point: 36 per cent of traffic today is generated by machines, not humans,” said Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) board of directors president Vivek Shah.

Even reputable publishers are victims

Until the ANA/WhiteOps study, many mainstream publishers took solace in the widely accepted notion that digital ad fraud was limited to low-end, small, and either sleazy or at least non-traditional digital publishers.

They were wrong.

Even the publishers who took the precaution of selling ads only on what are called “private ad exchanges” to tightly control their inventory and allow only brand-consistent advertisers on their sites have been victimised by fraud. Ten per cent of ad impressions from premium programmatic ad campaigns are fraudulent (triggered by bots).

“The surprise [in the study results] was the ubiquity of the fraud,” ANA VP Bill Duggan said. “It is not just no-name websites, but it also affects premium publishers.”

“Advertisers who assume that traffic to premium publishers is free of bots risk losing large amounts to intentional or unintentional bot fraud,” the ANA report stated. “The reputation of the publisher is no longer a reliable benchmark to predict bot traffic level.”

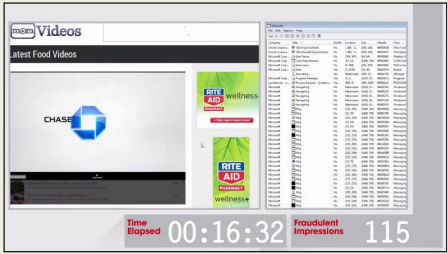

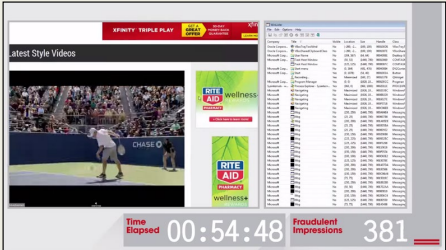

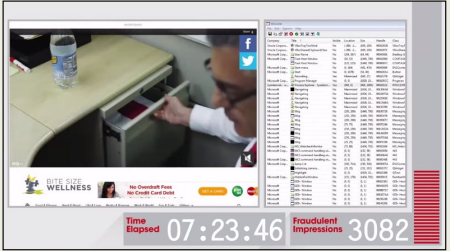

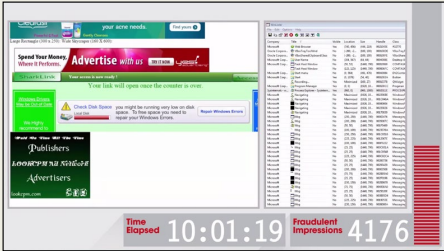

To demonstrate bot traffic in action, ad fraud-fighting company Forensiq infected one of its computers with malware, and recorded what happened next. The screen grabs above show how a single infected “bot” machine loaded thousands of webpages, and a total of 4,176 fraudulent banner and video ad impressions in just 10 hours, Forensiq said. Those fraudulent ads included major brands Verizon, Chase, Toyota, Tide, Buick, Aleve, Citi, Comcast, Sprint, Ford, and numerous others. According to Forensiq, the company’s malware-infected computer received instructions from an IP address located in Germany.

What exactly is a bot?

Let’s take a step back: What the hell is a bot?

Bots are very sophisticated software programs often installed on a consumer’s computer through seemingly innocent means (e.g., offers of free stuff if the consumer will click on an ad, fill out a form, or download a toolbar or browser extension). Those “bots” then “click” on ads or run videos silently in the background (behind the consumer’s active web browser screen or even invisibly). The consumers have no idea what’s going on, other than perhaps noticing that their computer might be running a bit more slowly. The advertisers and publishers think they’re getting real human interactions.

More sophisticated bots can collect consumer’s “cookies” (the URLs of websites they’ve previously visited or ads they’ve clicked). Those bots then appear to be “qualified leads” in the eyes of publishers and advertisers who think the ad campaigns are working.

As a result, the publishers and advertisers aggressively “optimise” their ad campaigns around these “consumers,” increasing their original campaign spending and budgeting new monies to retarget these “qualified leads.” Some advertisers and publishers will even “white-list” those bots, protecting the fraudsters from monitoring and guaranteeing them future business. Advertisers and publishers are actually optimising for fraud, exacerbating and perpetuating their initial loses.

Bots look like grandmas & tech geeks

Some publishers who haven’t kept up with the development of bots will be amazed and disconcerted to learn how sophisticated bots have become.

Many publishers believe they have insured their security and are separating human visitors from bots by requiring visitors to type in those maddening strings of letters and numbers — “CAPTCHAs” (an acronym for “Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart”). Bots can now fool CAPTCHAs.

Bots can also move a computer’s mouse and run the cursor over ads. Bots can buy things — putting them in shopping carts and actually executing a purchase.

Bots can visit multiple sites generating cookies that make the “user” appear demographically appealing to advertisers and publishers. Fraudsters’ program bots can behave like car buyers, sports fans, rich people, singles, or grandmothers. When fraudsters string hundreds of infected computers together, they have a “botnet” that generates high volumes of traffic and clicks from what appear to be very significant, specific, desirable audiences.

“So much for bots giving themselves away by acting like, well, bots. Turns out they can be made to act quite human, which is foiling efforts to detect them,” wrote AdAge tech reporter Alex Kantrowitz. Bot fraud is the world’s most sophisticated cybercrime, according to WhiteOps CEO and co-founder Michael Tiffany.

Why should magazine publishers care?

Magazine advertising survives and thrives based on trust and results. Advertisers trust publishers because they place their ads in the context of high-quality, relevant content delivered to high-quality, demographically appropriate, highly engaged audiences who deliver results.

Ad fraud wrecks every part of that equation: The content and ads are not seen by any audience and even superlative results are suspect and too often fraudulent.

“The amount of bot fraud in our midst is unrivalled in any other industry and is sadly leading to a crisis of confidence on the buy side,” wrote advertising security company Solve Media CEO Ari Jacoby in Advertising Age.

Six ways fraud hurts our industry

- Brands lose confidence in digital media

- Brands squander money on campaigns that are served to a high percentage of bots

- Fraud makes campaign success analysis suspect and less useful

- Fraud inflates inventory — other forms of fraud in addition to bots are fraudulent web sites, ad stuffing (hiding ads behind other ads), and ad injection (placing unauthorised ads on other publishers’ sites)

- The billions of dollars in ad fraud funds the bad guys’ development of high tech tools to defeat publishers’ defensive efforts

- Fraud invites government regulation by undermining the perception that our industry can control itself

The problem is huge, and it is not going away any time soon.

“As more ad inventory is bought and sold programmatically on ad exchanges, bad guys are finding it far easier to commit fraud because few agencies and advertisers actually check in detail the hundreds of thousands of sites on which the ads are run. It’s easier to hide in a far larger haystack,” according to New York-based Marketing Science Consulting Group founder, Dr. Augustine Fou.

What are the types of digital ad fraud?

Industry wags joke that asking ten different industry players to define ad fraud will result in ten different definitions. But our research into digital ad fraud has narrowed down the types of ad fraud to nine, the largest of which by far is ad impression fraud perpetrated predominantly by bots:

- Ad impression fraud (CPM)

- Search ad fraud (CPC)

- Affiliate ad fraud (CPA)

- Lead fraud (CPL)

- Ad injection fraud

- Spoofing fraud

- CMS fraud

- Retargeting fraud

- Traffic or audience extension fraud

1. Impression (CPM) ad fraud

Impression ad fraud has several parts:

• Hidden ad impressions

• Fake sites

• Video ad fraud

• Paid traffic fraud

• Ad re-targeting fraud

HIDDEN AD IMPRESSIONS: Hidden ad impressions (also called ad stuffing or ad stacking) come from fraudsters either placing teeny one-pixel-by-one-pixel windows throughout a web page and serving ads into those virtually invisible ad spaces, or stacking layers of ads one on top of the other in the same space but only the top ad is visible. Some pages observed in the ANA study found 85 ads on a single page where few if any ads were actually visible. Video ads can also be stuffed into 1×1 spaces or continuously looped in stacks so no user ever sees it.

The result is a huge ad inventory (tens of millions a day) on ad exchanges, all of which can be sold but few or none of which are ever seen. For example, an AdAge investigation found two examples of massive fraud: One fraudulent site (modernbaby.com) offered 19 million impressions per day on one exchange while another fraudulent site (interiorcomplex.com) offered 30 million ad impressions per day on another exchange.

FAKE SITES: Fraudsters create fake sites containing only ad slots and either no content or generic content often repeated from one fake page to the next. None of these sites draws huge traffic (to avoid creating suspicion) but networks of fake sites sold on programmatic ad exchanges can generate millions in revenues taken together.

VIDEO AD FRAUD: The explosion in the popularity of online video has drawn the attention of fraudsters. Fraudulent video ads are also as much as ten times more lucrative than banner ads thanks to higher CPMs. Fraudulent video ads are often stacked, invisible (the 1×1 windows), or played in the background (where the consumer can’t see them).

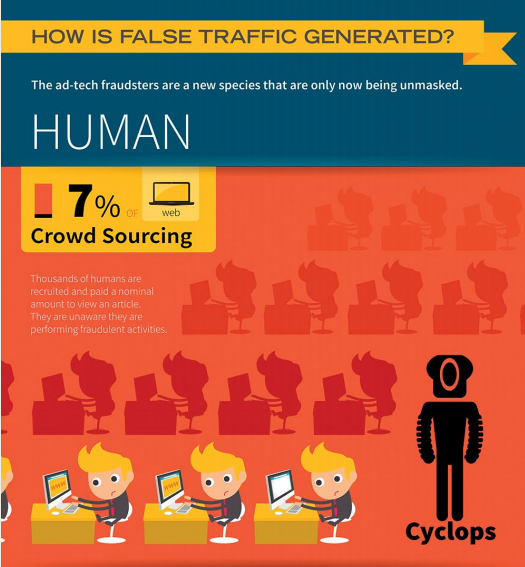

PAID TRAFFIC FRAUD: Publishers buy “traffic” from third parties to generate more unique visitors to their sites. The ANA/WhiteOps study found that 52 per cent of that traffic is from bots, and occurs most often between midnight and 7am.

RETARGETING FRAUD: Bots can be programmed to mimic specific and highly desirable consumers’ online behaviour, such as home- or car-buyers. The bot goes to relevant websites and acts like a consumer interested in making a purchase, researching topics and clicking on ads, but not necessarily actually making a purchase. That behaviour triggers a campaign of re-targeted ads hoping to convince the “hot prospect” to make the purchase — but those prospects are really just bots. Nonetheless, the fraudulent ad targeting company makes money.

2. Search (CPC) ad fraud

Fraudsters select the most expensive keywords — the ones with the highest cost per click (CPC). They then build their own websites and load them up with the high CPC keywords to generate search ads. The whole process is automated and the sites are generated by algorithm at a dizzying pace to maximise potential revenue. Brands looking to advertise against those popular keywords buy inventory on the fake sites. When the fraudster’s bots click on the real ads, the advertiser gets a report that makes it look like the click came from a real, respected website.

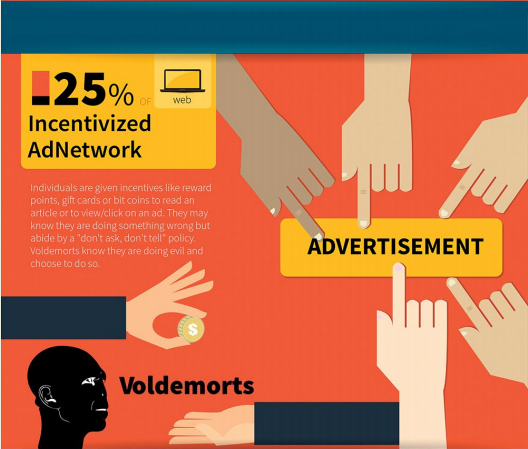

3. Affiliate (CPA) ad fraud (AKA cookie stuffing)

Affiliate marketing programmes reward websites for getting visitors to complete an action such as filling out a form or making a purchase. Affiliate or Cost Per Action (CPA) fraud consists of a fraudster manufacturing fake actions by using bots to direct qualifying traffic to affiliate sites or stuff a consumer’s computer with fraudulent cookies so that if that user goes to the affiliate’s site, the fraudster collects the referral or commission payment. Often, the stuffed cookies will override any legitimate cookies and rob the legitimate referrer of earned income.

4. Lead (CPL) ad fraud (AKA conversion fraud)

This is the type of fraud most publishers believe is impossible. Computers can’t possibly fill out forms, right?

Wrong. What started with the bad guys employing small armies of people in under-developed countries to fraudulently fill out forms for pennies each, has rapidly morphed into a completely automated fraud industry where bots can fill out thousands of forms in the blink of an eye in a way that fools most publishers’ rudimentary anti-fraud systems.

5. Ad injection and AdWare fraud

Not too long ago, a Target ad ran right in the middle of walmart.com. Walmart did not sell the ad, but there it was, big as day, promoting a Walmart competitor on Walmart’s own site. The culprit was the latest in digital advertising fraud: Ad Injection. Perpetrators of this line of fraud offer consumers what appears to be an innocent incentive, usually a web browser tool bar or extension. Secretly embedded in the tool bar or extension, however, is software that injects onto unsuspecting sites advertisements that deliver no revenue to the site itself but to the tool bar creator.

The fraudsters who create these tools do not tell the consumer about this feature of the toolbar or extension. And they certainly do not pay the publishers or brands on whose site the ad is injected. But the fraudsters do list the inventory on programmatic ad exchanges as being on that legitimate publisher’s or brand’s site (but they never get the publisher’s or brand’s permission).

The fraudsters who create these tools do not tell the consumer about this feature of the toolbar or extension. And they certainly do not pay the publishers or brands on whose site the ad is injected. But the fraudsters do list the inventory on programmatic ad exchanges as being on that legitimate publisher’s or brand’s site (but they never get the publisher’s or brand’s permission).

Some of the biggest brands and most reputable publishers in the world have been victims of this type of fraud, including Walmart, Home Depot, Macy’s, Dell, Samsung, Yahoo, MSN, weather.com, YouTube, and Yelp, according to AdAge.

The ANA/WhiteOps study also found rampant injection fraud, including one publisher whose site was hit with 500,000 injected ads every day for the duration of the two-month study.

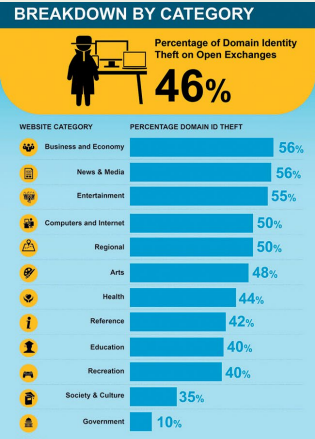

6. Domain spoofing or laundered ad impression fraud

Domain spoofing fraud may be the most insidious and most difficult to detect and prevent, and most lucrative for the bad guys.With a simple line of code, fraudsters can change the URL of sites, even sites on white lists and private ad exchanges, to make advertisers think fake or piracy or porn sites are really the sites of reputable publishers.

Because advertisers assume that premium publishers are the best places for their campaigns, they put those publishers’ sites on their whitelists. Whitelists are presumed not only to be the best sites with the best audiences, but also to be a safe defensive bulwark against ad fraud. As a result, premium whitelisted sites command top bid prices on exchanges.

Ironically, whitelists by their very nature attract fraudsters. The potential for inordinately high CPMs with little risk of discovery has prompted fraudsters to find ways to develop code that enables them to mask their fake, piracy or porn sites as one of the sites on the whitelists.

Domain spoofing comes in two varieties

The first involves malware consumers accidentally install on their personal computers. The malware actually injects ads windows onto websites the consumer is viewing. In a nanosecond, the fraudster is able to offer that space on what looks like a premium publisher’s site out for bidding on an exchange. The price the fraudster commands reflects an incredible discount for such a desirable site. The money for the ad flows to the fraudster, not the premium publisher. This type of fraud is hard to detect because the user really is on the premium publisher’s site.

The second approach to domain spoofing involves fraudsters modifying codes in the ad tags that identify the domain a user is viewing. The managers and users of ad exchanges must be able to assume that the ad mark-up codes are always accurate. Sadly, such is not the case. Fraudsters can easily delete the mark-up code and replace it with code that enables them to impersonate any premium site they choose.

7. CMS fraud

In this approach, bad guys hack into a publisher’s content management system (CMS) and create their own pages using perfectly legitimate domains. Then they put those pages on ad exchanges with the premium publisher’s mark-up code, but the advertiser who purchases those positions gets pages with no premium content and pays the fraudster instead of the publisher.

8. Re-targeting fraud

As discussed earlier, fraudulent operators can program bots to imitate very specific, very desirable types of consumers, from sports fans and home-buyers to tech geeks and grandmothers. Those bots then browse relevant websites in a way that makes them look like a qualified sales prospect, including clicking on ads and filling out forms. These actions create very valuable cookies that advertisers covet because the target appears ready to make a purchase.

9. Traffic fraud or audience extension fraud

Sometimes publishers need to drive more traffic to their sites, most often to fulfil a promised number of impressions for advertisers but also sometimes to boost the number of unique visitors.

“A publisher might book a million dollar ad campaign with an advertiser, but for whatever reason, they have shortfall of (impression) supply,” Casale Media vice president Andrew Casale told FIPP. “So they will buy programmatic media with the advertiser’s budget to fill shortfall. Publishers go out and buy the traffic from sites they believe to be similar to their own, but third-party sites have the highest percentage of fraudulent traffic.

“The advertiser awarded the ad budget to the publisher at a high CPM because the impressions would be appearing on a trusted brand site,” said Casale. “But if the publisher betrays that trust and buys traffic on sites not of the same quality, and that gets back to the buyer, you’ve harmed your brand and your relationship. Those publishers are effectively feeding the problem they are trying to solve.” Where does the fraud originate? The ANA/WhiteOps study found that 67 per cent of the bots observed in the study came from residential IP addresses. The study researchers also found that a small percentage of highly compromised computers create the bulk of bot traffic.

Who are these bad guys?

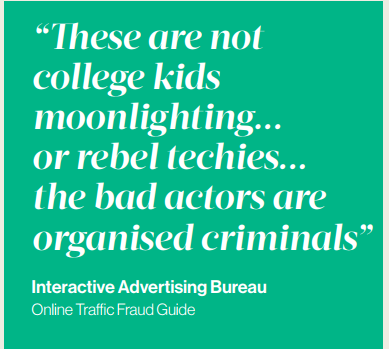

These fraudsters are not college kids or individual hackers writing malevolent code in their spare time. A 2013 Adweek piece pointed the finger at “organised crime, Russian millionaires, exbank robbers, and one-sixth of the computers in the US.”

That may be true, but the Internet Advertising Bureau’s own “Online Traffic Fraud Guide” stated clearly: “These are not college kids moonlighting to make some cash or rebel-techies in their Bay-area apartment. The bad actors are organised criminals, usually operating outside of the United States and are often funded by larger criminal organisations.”

How do they make money?

In every case, the bad guys make money by:

• Selling fraudulent ad impressions

• Selling fraudulent traffic to publishers looking for more visitors

• Selling their own ads on other publishers’ sites without the publishers’ knowledge or permission

• Sending fraudulent traffic to affiliate sites in return for a commission

• Creating fraudulent sites that look legitimate and selling advertising on those sites

Disincentives to change

The only way digital ad fraud could have become so egregious is because nobody cares, WhiteOps CEO Michael Tiffany told AdAge.

It’s an attitude problem: There is not enough incentive to fight fraud. No one — advertisers, publishers, ad exchange managers — wants to admit that they’ve been fooled, wasted money, bought bad inventory, or inflated results.

Besides, removing the fraudulent impressions would translate into lower (but more accurate) performance reports, lower (but more accurate) traffic reports, and lower (but more honest) income for ad exchanges. In the short run, it would appear no one would win by eliminating fraud, and a lot of people fear they would be made to look the fool in the process.

“Only by emancipating your people and partners from that fear can we get the cooperation needed to address this issue effectively,” the ANA study concluded. “Too many people are engaging in acts of omission, where you turn a blind eye, and it’s, ‘Well this is common practice, everybody buys traffic from this source, so I’m just doing what everybody else is doing.’” IAB executive vice president Mike Zaneis told AdAge. “That’s not going to be okay anymore.”

So how do we beat these guys?

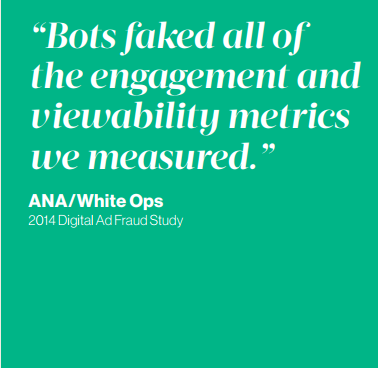

Many defences against the dark arts have already been defeated: The ANA/WhiteOps study discovered that several tactics publishers and advertisers believe are effective in preventing bots are, in fact, mostly ineffective: “Bots faked all of the engagement and viewability metrics we measured,” the report stated.

Viewability does not ensure humanity because fraudster bots can fake it. Bots record ads as viewable when, in fact, they are running in the background or totally invisibly. Actually, viewable impressions in the study skewed slightly higher in bot incidence than non-viewable impressions. And bots have learned to exquisitely mimic human behaviour, thus defeating engagement metrics.

Another favourite strategy of publishers and advertisers — blacklisting of fraudulent sites — not only requires near real-time updating, but those sites are also quickly and easily replaced by new bad guy sites. Ironically, blacklisting often ends up blocking real humans as well as bots.

“We are [in] an arms race and we’re saying it is acceptable to fight this by playing a carnival game: Whack-a-mole,” Casale Media vice president/strategy Andrew Casale told the IAB Ad Operations Summit in November 2014.

“We are playing a game with bad guys who have millions of dollars [from] defrauding our ecosystem and we are not winning this game,” Casale said. “Any notion that the volume of these [fraudulent] sites is declining is not what we’re seeing. Suspicious new activity is increasing dramatically, so the game of whack-a-mole is getting harder every day.

“We’ll take one name off the chart and stop paying them, but by that point they’ve probably made thousands or tens of thousands of dollars and they simply go out and spend eight bucks to buy a new domain and they’re back in business.

“If our line of defence against this is to block one domain at a time, it’s too slow,” Casale said. “We have to go beyond that to know for each of these clusters who is the organisation we are paying the money to, what’s the name on the cheque? That’s how we can easily identify these clusters and tighten up our supply side.”

A check-list of defensive and offensive anti-fraud measures

Four of the anti-fraud industry’s leading executives gave us their strategies for detecting and preventing ad fraud:

Scott Knoll, CEO and president, Integral Ad Science:

“Do not buy traffic from anyone else. If you don’t buy traffic, you’ll have virtually no fraud.”

David Sendroff, founder and CEO, Forensiq:

“The first task is going to sound odd, but it’s to make a very serious commitment to fight fraud. Create a publicly stated or corporate statement. Then join the industry’s Anti-Fraud Working Group. Membership signifies commitment and helps keep you up to date.”

Andrew Casale, vice president/strategy, Casale Media:

“The number one thing to do is protect and police your identities. Programmatic buying and selling have become so automated, it’s easy for anyone to pretend to be anyone. If you are engaged in programmatic and trading alongside a phantom who has your name but is selling it at a fraction of your cost, it is the worst thing in the world. Enforce your right of trademark.

“The number one thing to do is protect and police your identities. Programmatic buying and selling have become so automated, it’s easy for anyone to pretend to be anyone. If you are engaged in programmatic and trading alongside a phantom who has your name but is selling it at a fraction of your cost, it is the worst thing in the world. Enforce your right of trademark.

“Then make sure your partners are as concerned about ad fraud as you are. They are the exchanges where you list your impressions and third parties where you buy traffic. Look at the neighbourhood of the exchanges where you put your impressions. If you spent tens of thousands of dollars to give your  home a high market valuation but you put it in a really bad neighbourhood, its value will suffer. Make sure you are trading alongside publishers of similar status, not a site masquerading as Disney, which happens every day.”

home a high market valuation but you put it in a really bad neighbourhood, its value will suffer. Make sure you are trading alongside publishers of similar status, not a site masquerading as Disney, which happens every day.”

Michael Tiffany, CEO, White Ops:

“You need to make sure your own house is in order first. We have found again and again huge media companies with bot traffic because someone at that organisation who is responsible for growing audience is going to third parties to buy traffic and that third party is giving the publisher bots. The leadership has no idea what’s going on; as a matter of fact, they are surprised to find out they have been goosing their audiences by 10 per cent, which is a big deal because they’ve been selling their inventory as premium inventory, the most expensive on the market. Do not pay for fraudulent traffic.”

All four executives advocated changing the way ad impressions are sold and success is measured.

“The problem is really the industry’s own fault — we’ve been optimising for quantity and have created this crazy breeding ground for fraud,” said Knoll. “Advertisers are saying we’ve got to get rid of fraud, but at some time they’re using metrics that encourage fraud. You can’t have it both ways.”

They also all said, no surprise, that publishers should hire companies like themselves to detect and prevent fraud. As self-interested as that sounds, they’re absolutely right.

“The benefit of using third party solutions is that we can leverage tech algorithms and huge fraud database,” said Integral’s Sendroff. “We look at a couple of trillion bid requests a month. And we have that massive central database. Our systems allow publishers and advertisers to cleanse inventory and traffic before they buy or sell. This is our core competency. Fraud is constantly evolving, so it is important to have experts.” We agree.

Certification and standards were another popular solution for not just detecting but actually preventing and, eventually, eliminating fraud. “There is no  accountability now; too many people can hide,” said Casale.

accountability now; too many people can hide,” said Casale.

“Transparency will rise, so if you’re doing bad things, you won’t be able to hide and you won’t get paid. If you’re doing good things, you should embrace certification because, while it may be a bit of a burden and may cost money, you will never again be in the position of having someone making money off your back. As soon as we make it hard to trade and hard to hide and hard to get paid, we will win.”

Other strategies: Make exchange floor prices and provider names public

Publishers themselves could take a big step toward outing fraudsters by simply creating more transparency in their exchanges policies. For example, if  publishers made their floor prices public, advertisers would be instantly alerted of possible fraud when they saw premium inventory listed at prices below the published floor price.

publishers made their floor prices public, advertisers would be instantly alerted of possible fraud when they saw premium inventory listed at prices below the published floor price.

And the exchanges could take another big step with an equally simple but powerful solution: Before placing a bid on an ad exchange for an ad impression, the buyer must be given the name that would appear on the cheque paying for that impression. Instead of relying on domain names (which we’ve shown can be faked), advertisers could rely on the name of the organisation they’ll be paying.

Using this system, advertisers and publishers could create reliable whitelists by including Hearst or Bauer or Kodansha or Abril or China Publishing Group — the names that would appear on the cheques – instead of “cosmopolitan.com” or “veja.com” which can be spoofed.

“We must create conditions where a lot of companies can take the action to clean the bots out in 2015,” said WhiteOps CEO, Tiffany. “If we do a better job with transparency and detection, they will make less money and they’ll have less money to make better bots. We need an army of white hat hackers to reduce the buying power of the dark side. If a criminal operator has a choice of type of crimes and the ad fraud profit pool gets smaller, suddenly it is a far less attractive thing to do. Think about the effect on market. It would mean putting US$6 billion back in the publishing industry!”

The good news: The consensus of the antifraud executives is that 2015 will be the beginning of the end of widespread ad fraud.

INNOVATION’S TAKE:

The publishing industry has no choice but to start fighting digital ad fraud in a coordinated, big-picture, sophisticated fashion. Too much money is being lost at a time when every penny counts, and the fraud also has the potential to wreck not only our bottom line, but also our reputation.