05 Feb How do you create a news start-up culture without gimmicks

If legacy media are not part of the innovation process, they will not only give up their current market share but will lose any chance of competing for their future.

Small teams of annoying visionaries, developers and product designers, with newly invented roles, channel an extraordinary amount of financial investment around the world, pursuing one goal: using technology to generate disruptive, scalable evolution that provides exponential returns to investors.

The start-up ecosystem, well stocked with talent and money, has built a virtuous circle of innovation in which every project (regardless of its level of success), every professional, every lesson learned and every investment is part of a technological evolution that has radically changed the media landscape in the last 20 years. Legacy media must become a part of this innovation process, but what is it that makes start-ups so special?

Shannon Gausepohl, the associate editor of Business News Daily, asked some leaders to identify the key elements of the start-up culture. She found 3 things: an “anything is possible mentality”, the ability to learn and react quickly, and employees and leaders who own their contributions.

Legacy media companies have much to learn from that fearless approach. They should not try to imitate start-ups directly though, because most start-ups fail, and that’s an essential part of their world. Victimless failures encourage risky decisions and bold bets. That is not, however, the way to manage a 100-year old newspaper.

Three elements work in favor of legacy media brands: time, money and brand. Strategies can be transformed and managed, funding is normally available, and existing brands provide initial recognition.

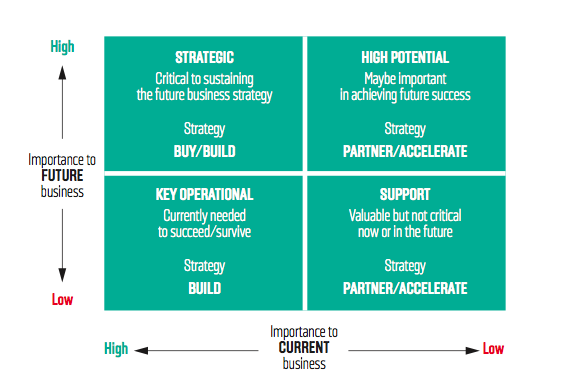

With those three elements, there are four ways companies can engage in start-up like behaviour.

Firstly, they can partner with start-ups, and establish privileged partnerships, leveraging the existing brand and market positioning. There is little to no risk, and perhaps the project does not require much up-front investment, other than opportunity cost. Failure, or success, will be quickly apparent and it might lead to some long term collaboration. If handled badly, however, the start-up might receive more leverage than it is worth, and the business might not see a return on its investment of time and resources.

Secondly, a legacy company can just build it themselves, if it already has the people and a knowledge of the problem. This is a great option for urgent strategic developments. Flexible market leaders can get this done. Organisations maintain full control, do not depend on anyone else and can use existing business resources. They are already familiar with the market. They might find it hard to compete against “real” start- ups, though, or find the right talent to work on the project.

The third option is to buy the start-up, or invest in it. There is a constant flow of new ideas and projects that escape their control and even their knowledge, but they eventually end up dramatically affecting their businesses. This choice provides more insights than partnership, information must flow, and companies can keep an eye on product development. They also get to keep the returns if it works, and benefit from the knowledge of the employees they acquire.

As Tim Cook would put it: “We buy companies with really smart people. We take that talent andput them to work on projects that are in line with Apple’s own strategy”. Deal flow is the key, though. Legacy media companies do not have a systematic start-up scouting process: how can they make sure the best projects arrive at the right time? Over a period of two years, Google talked to more than 2,200 companies, but only 2%—or about 55—led to an acquisition. Are we ready for that?

Finally, we have the concept of start-up accelerators. Their role is to attract a large number of early stage start-ups, filter and select some of them, invest a small amount of money in each one—typically $25,000-$100,000—in exchange for 2-5% of the stock, and put them through a business bootcamp. Paul Graham’s Y Combinator is the mother of all accelerators and its portfolio is filled with start-ups that became Airbnb, Dropbox, Stripe or Weebly, to name just a few.

The media industry has spawned two variants on this theme: corporate accelerators and media accelerators. Corporate accelerators are promoted and funded by a single company to attract early stage projects that might fit their future strategy. Axel Springer is the most relevant example, with Axel Springer Plug and Play. It has made more than 90 investments in early stage businesses since 2013, for a total cost of €100 million. Socius is a native ad platform, Zeniad a virtual reality ad delivery platform and Blogfoster a blog platform for influencers.

Media accelerators are VC funds owned by a consortium of legacy media companies. They only deal with media start-ups, including tech solutions such as metrics, platforms or ad formats. Matter was founded in 2012 by Jake Shapiro and Corey Ford. It is the benchmark for media accelerators, has offices in San Francisco and New York City, and an impressively long list of investors, from the Associated Press to the Knight Foundation.

They have helped 49 start-ups so far. Every year, Matter screens the market and selects 12 start-ups (six on the east coast and six on the west coast). They invest $50,000 in cash (plus $75,000 in acceleration services) in each one and accelerate them through a 20 week program. They also invest in follow-up rounds.

NewsWhip, for example—an app that tracks and predicts the stories, events and people getting engagement on social networks—got $6.4 million in a Series A round in February 2017.

The bootcamp focuses on human-centred learning and prototype-driven process, with lots of workshops, speakers and sessions with expert mentors and partner executives. On demo day, teams present their projects to a curated community of investors and media executives.

This method mixes media start-up founders, partner executives, experts, mentors and advisors together. You might find Nick Rockwell, the New York Times’s Chief Technology Officer, and a member of Matter’s Advisory Board, attending a design thinking session and drawing wireframes on a whiteboard. There is extraordinary value for partners and investors in this method. On the one hand, they get to invest in an amazing portfolio of media start-ups that are likely to be the next disruptors, so there’s an obvious financial incentive. On the other, it is an effective way to stay in touch with the latest trends, to get first hand information of every shiny new project in the industry, and to take advantage of early stage projects to grow their investments before they become too expensive.

Start-ups that have been helped by Matter include News Deeply, which builds single- subject information hubs like Syria Deeply, and Nuzzel, a platform that lets you see your friends’ top news stories.