04 Jun The Challenge of Generative AI

Since ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence tools burst into the public consciousness, only a few short months ago, the media industry has had to go through several phases of reckoning. What started as mild curiosity quickly morphed into concern, and a fair bit of doom mongering, about how large language machine models could make journalists obsolete. While that initial pessimism has given way now to a more positive outlook on the technology itsef — expresses through a series of rules and guidebooks now being developed to effectively incorporate AI into newsrooms of all sizes, a larger question has always seemed to loom large.

In hindsight, for the media industry, this was always the going to be the elephant in the room question — how long would we spend marvelling at the capabilities and possibilities of this new technology before thinking about how it would structurally affect our businesses? From our now traditionally unfruitful relationship with Big Tech, of which ChatGPT and others are just the latest iteration, we have learned (hopefully!) that the spiral starts with giving our content away for free.

CONTENT WITHOUT CONSENT

It is only apt then, to start our chapter covering the effect that generative AI has had on the news industry, with these larger questions now being raised by industry leaders.

We will circle back, of course, to the ways in which generative AI can be incorporated in newsrooms, but it is crucial to view those developments inlight of what the rapid development of the software could mean for the business of the news industry.

At the Internationla Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy earlier this year, Daisy Veerasingham, the chief executive of the Associated Press said that generative AI engines built on

content scraped from publishers pose an “existential threat” to media owners unless regulators impose laws around attribution and ownership.

“There is no doubt it poses a serious challenge to our intellectual property, and that is a big concern to all content creators and originators of media,” Veerasingham said, as quoted by the International News Media Association (INMA). “We have to as an industry come together to create a legislative framework that will better protect our IP because these tools are learning and are becoming smarter as a result of the work that we do. We need to ensure that we are protected. Otherwise, we will face an existential threat if we don’t respond in that way.”

“We can’t allow what happened with search to happen again,” she said again at the festival, in comments during a session on a new generation of media

CEOs. The AP, Veerasingham said, had been taken by surprise at the scale of its content that had been ingested by Open AI to help build the large language model that powered its ChatGPT engine.

She urged publishers and legislators to move fast and decisively to protect the ownership of content. In response to a later question from INMA, Veerasingham elaborated

on her concerns that the corpus of Associated Press — along with Reuters and virtually all other international publishers — had been absorbed by Open AI to create the model that powers its generative AI tools.

“We were surprised, and that’s why I make my point that it is an existential threat if we don’t figure out how to protect everybody’s copyright because it’s about all of the content that these systems are using that will make them smarter, that will make them be able to compete with us,” she said. “We have to be honest about that they will be able to compete with us if we don’t work out ways of protecting our intellectual property.”

Here’s how Peter Bale, Newsroom Initiative Lead at INMA, sums up the problem that news organisations now have to grapple with: “It turns out that the question of how

CHATGPT attributes the source of content is a very big question, but maybe not as big as the fact that OpenAI has already ingested probably everything you’ve already published to the Internet, ever. It raises important issues about sourcing, trust, payment to content creators, or even recognition that they exist, as well as future sources of revenue for this new type of search engine.”

“Just as big an issue may be the fact that OpenAI — a non-profit organisation originally dedicated to the ethical development of Artificial Intelligence but with a for-profit arm

that intends to commercial tools like ChatGPT — already has and has used your content to create the corpus from which it draws its weirdly uncanny answers to almost any question,” he adds.

Bale references a list put on Twitter recently by the computational journalist Fracesco Marconi, with what appears to be the entire training set of data that Open AI used to build

ChatGPT. “It is a remarkable list and it would almost be easier to try to find publishers who aren’t there than tell you whose content was scraped to create the ChatGPT base of

information,” he writes.

“The Guardian, New York Times, BBC, and Reuters are all there. FAZ, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, and McClatchy are on the list. Netflix is in there as well. There are an initial 1,000 sites on the list, and one can perhaps assume there are many more below the top 1,000.” Speaking at the Deloitte and Enders Media and Telecoms Conference 2023, held earlier this year, Jon Slade, chief commercial officer at the FT, said “there’s very good evidence” that his paper’s archive had been used to train large language models.

“And it’s been used without our consent, it’s been used without a licence. It leaves me slightly conflicted – but only slightly conflicted – because as a chief commercial officer I think there should be a payment or whatever for that,” Slade added in comments reported by Press Gazette. “But on the other hand, I’m glad that our quality journalism is part of these get down the risk of misinformation, but it doesn’t detract from the issue of the licence where it’s necessary.”

Press Gazette reported that Slade likened the lack of payment to publishers to the period in which news publishers began to widely publish online free of charge. “The key issue for publishers, 20 years ago, was that a lot of them gave their content away for free. And they can do that again. And we would see a similar level of disintermediation, or probably a much greater level of disintermediation, through [our content’s] synthesising and use in products that we don’t control but we have contributed to.

“So I think we have to remember that we’ve seen the movie before. We’ve got to get control of our IP and manage it fast.”

He said regulation would be “slightly useful in that sense”, but that he was worried “that the tone of some of the regulatory conversation seems to index more, currently, towards ensuring that AI businesses have access to data, rather than protecting existing copyright and IP regulation that already exists”.

AN EXISTENTIAL THREAT

The Deloitte conference brought together a host of top media industry leaders and all were in agreement.

Guardian Media Group chief executive Anna Bateson similarly said she would like to see both payment and attribution for her publications’ content from AI companies. “If our content – that it costs a considerable amount of money and investment to produce – is being used to train models which are then incredibly powerful, and the basis for incredible value creation, then there needs to be some sort of acknowledgement of that.”

Le Monde chief executive Louis Dreyfus perhaps had the strongest statement of all, saying that a lack of acknowledgement and payment for news content used by generative AI machines could spell “the end for our business model”. As per Press Gazette,

Dreyfus described the situation as “an emergency” and said “we need to define a common position” and establish “what AI companies are ready to put on the table for use of all content”.

“Otherwise it’s the end of our business model. If somebody can type a question, or write stories, using our content or mixing it with some lowquality content, it’s a risk for the

political debate, political society.”

Asked what opportunities he saw for journalism in the age of generative AI, the French newspaper boss said: “I strongly believe there is more risk than opportunities for us. Our business model is based on trust. With AI, we are taking the risk of less reliability and less exclusivity.”

There are more aspects of this consider. In a detailed piece covering publisher’s concerns around generative AI published earlier this year, The New York Times’ media reporter Katie Robertson writes about the potential implications for search traffic. “Many sites get at least half their traffic from search engines. Fuller results generated by new chat- bots could mean far fewer visitors,” the subheading to her article reads.

Robertson writes that new AI tools from Google and Microsoft give answers to search queries in full paragraphs rather than a list of links. As a result, many publishers worry that

far fewer people will click through to news sites as a result, shrinking traffic — and, by extension, revenue.

Many publishers, she writes, “are pulling together task forces to weigh options, making the topic a priority at industry conferences and, through a trade organisation, planning a push to be paid for the use of their content by chatbots”.

News Corp’s chief executive, Robert Thomson, who for years has led a push to get tech companies to pay for news content, said in an interview that tech companies should pay to use publishers’ content to produce results from AI chatbots. The chatbots generate their results by synthesizing information from the internet. He added that News Corp, which owns The Wall Street Journal and The New York Post among other outlets, was in talks with “a couple of companies” about the use of its content, though he declined to specify which ones.

“There is a recognition at their end that discussions are necessary,” he said. Roger Lynch, the chief executive of Condé Nast, which owns titles like

Vogue, Vanity Fair and Glamour, agreed that content creators should be compensated. He said one upside for publishers was that audiences might soon find it harder to know what information to trust on the web, so “they’ll have to go to trusted sources”.

The News Media Alliance, which represents 2,000 outlets around the world, including The New York Times, has published principles that it says should guide the use and development of A.I. systems, and regulation around them, to protect publishers. The guidelines say the use of publisher content for the development of A.I. should require “a negotiated agreement and explicit permission”. The NMA also call on tech com- panies to “provide sufficient value” for high-quality, trustworthy journalism content and

brands, and state that any new laws or regulations that make ex- ceptions to copyright law for A.I. must not weaken protections for publishers. “Without these protections, publishers — far too many of whom already struggle to survive in the online ecosystem due to marketplace imbalances — face an existential crisis that threatens our

communities’ access to reliable and trustworthy journalism,” the document states.

“NO PLANS TO LEAVE”

For now, despite a multitutde of voices in media and other industries raising concerns around copyright issues related to generative AI, it looks set to stay and presumable fight the long fight on some kind of regulation. In May this year, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman U-turned on a threat he made earlier to leave the EU if it becomes too hard to comply with upcoming laws on artificial intelligence (AI). As the BBC reported, the EU’s planned legisaltion could be the first to legislate on AI which the tech boss said was “over-regulating”.

The proposed law could require generative AI companies to reveal which copyrighted material had been used to train their systems to create text and images. “We are excited

to continue to operate here and of course have no plans to leave,” Altman tweeted.

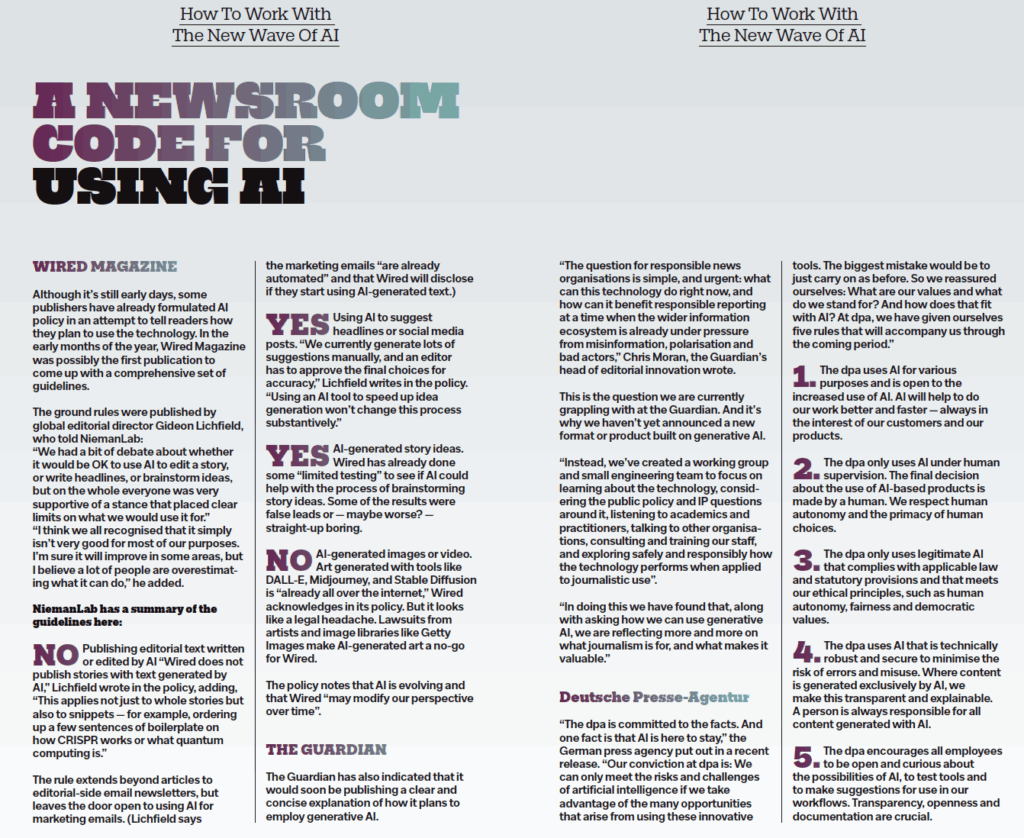

Which all bring us then, to the question of how generative AI can be incoprotated into newsrooms and workflows. While the industry as a whole does indeed need to come

together to address questions like copyright and payments to news publishers, it is also not feasible to pretend that the new technologies do not exist. Two key questions need to addressed however:

1) How do we make AI work for us? Generative AI models like ChatGPT can do many things, but they rely solely on what has happened and been documented. Compared to

virtually every other industry, news publishers have the upper hand here because only editors and human beings can tell original stories and report from the ground. AI cannot

literally write the future of our industry but it can help make the work of journalism more efficient.

2) How can newsrooms leverage the power of AI for journalistic work without becoming over-reliant on it? It’s fairly clear already that generative AI like ChatGPT can produce

large volumes of content. While that may be useful, news oganisations have to formulate a code or guidelines for what it can and should not be used for.

The global discussion on guidelines, suggestions, and insights for how to adapt to generative AI and how to use it to help journalism and make organisations more efficient has already produced a lot of literature, going back even before the ChatGPT era. Here’s a round up of the key themes so far:

THE THREE WAVES OF AI

Let’s rewind a bit here and zoom out to a larger perspective on journalism and AI. It was just one year ago, writing a chapter on AI for this book, that we documented several use cases on AI helping publishers with personalisation and predictive paywalls. And while we started to detail some instances in which news organisations used AI to generate stories, we did wager that we were yet to reach the point of robots writing cogent stories.

ChatGPT changed that entire narrative, of course, popping up suddenly and vividly like something straight out of sci-fi. But it’s worth re-emphasising that outlets have been using AI to support — and even produce — journalism for some time now.

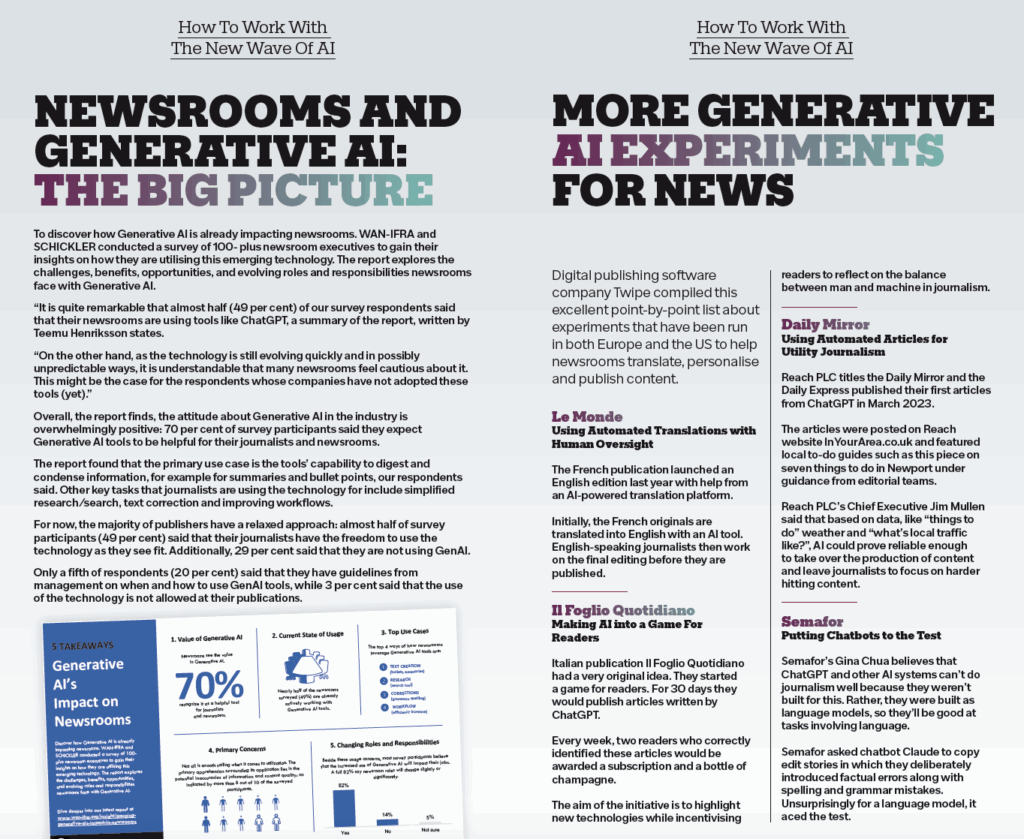

Speaking to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) in a recent piece, Francesco Marconi, a computational journalist and cofounder of the real-time information

company AppliedXL, categorised AI innovation in the past decade as occuring in three waves: automation, augmentation and generation.

During the first phase, “the focus was on automating data-driven news stories, such as financial reports, sports results, and economic indicators, using natural language generation techniques”. News publishers such as Reuters, AFP and AP were automating some content.

We can chart a few prominent examples here, among many:

l The Associated Press uses AI to produce data-driven sports stories and templated game recaps.

l McClatchy has used automation to cover local real estate sales.

Financial newswires like Dow Jones, Bloomberg and Reuters have experimented with automation to streamline coverage of earnings reports and the stock market.

PA Media’s RADAR newswire has generated more than 600,000 articles since it was launched in 2018, each a local story extracted from a national dataset. Stavanger Aftenblad in Norway covers 10,000 junior league football matches a year using automated text and a single reporter.

According to Marconi, the second wave arrived when “the emphasis shifted to augmenting reporting through machine learning and natural language processing to analyse large datasets and uncover trends”. Take the Argentinian newspaper La Nación for instance, which began using AI to support its data team in 2019. It then went on to set up an AI lab in collaboration with data analysts and developers. (It’s a fascinating example, and we’ll cover it in a separate section in this chapter so look out for that one!)

The third and current wave is generative AI, according to Marconi, and it’s “powered by large language models capable of generating narrative text at scale”. This new development offers applications to journalism that go beyond simple automated reports and data analysis. Now, we could ask a chatbot to write a longer, balanced article on a subject or an opinion piece from a particular standpoint. We could even ask it to do so in the style of a well-known writer or publication.

Part of the reason why ChatGPT and other tools have generated so much excitement is that they are so consumer-friendly and can communicate in natural language, says

Madhumita Murgia, who was appointed AI editor at the Financial Times in early 2023, in the same Reuters Institute piece”. Her role was newly created at the FT, to lead coverage about the rapid developments in AI. “It feels like there’s an intelligence there, even though it is really still just a very powerful sort of predictive technology,” she says.

Now that the technology is so advanced and accessible, reporter Sara Fischer of Axios notes, it’s become harder for newsrooms to draw the line between leveraging AI and becoming over-reliant on it. That’s an area that has already caused some recent controversy in media organisations that have begun to test just how porous this line may be.

A quick caveat before we dive headlong into AI and the newsroom: the meteoric rise of ChatGPT has given rise to an unprecedented volume of writing and reflection on the power of AI and the implications that it could have for journalism. Some are outright doom mongering, and others have chosen instead to look at the potential value that AI can bring to publishers. In many of these articles and reflections, there is a merging of generational AI technologies, a very new wave of AI, with older iterations that automate

tasks, and can now be seen as an older wave. Does this distinction matter? “What ties this disparate collection of technologies together is their ability to process large volumes of information, to a greater or lesser degree, on their own,” media analyst Peter Houston writes.

For now, as we move on to the next part of this chapter, that is a useful framework to think of all AI technology, with the acknowledgment that new tools like ChatGPT have supercharged their potential utility.

(And a side note: the use of AI for things like dynamic paywalls, personalisation and understanding user preferences may already seem a little mundane, at least in this moment, but the use of machine learning for these functions remains vital for news organisations. You can find a detailed round-up of these “older” technologies in our AI chapter from last year).

AI AND IMPROVING THE WORK OF JOURNALISM

Marcela Kunova, in a piece for journalism.co.uk published earlier this year, writes of some of the reliable and ethical ways in which journalists and newsrooms could leverage the power of ChatGPT on a daily basis, ranging from generating summaries, emails and social posts to providing quotes:

1.Generating Summaries of Large Texts and Documents ChatGPT is fairly good at summing up long pieces of text. This comes in handy when you need to quickly scan new reports, studies and other documents. You can even ask the tool to give you the most important points, pick up a quote or find information about the author(s).

2.Generate Questions and Answers When you are working on a topic you are not that familiar with or looking for new angles, ChatGPT can help you conduct research. For instance, you can ask it to give you names of experts to interview about a given topic and it generally comes up with sound suggestions. However, if the topic is too niche, the tool may generate totally plausible names that sound like they could be experts but are not in fact real.

3.Providing Quotes You can ask ChatGPT to look for quotes from a particular individual and chances are that it finds them. However, check where a quote comes from as it

could be another writer’s work — and this is plagiarism — or it could be made up. Since AI is not bound by the same ethical standards as human journalists, it may include quotes from sources that do not actually exist, or even attribute fake quotes to real people.

This could lead to false or misleading reporting, which could damage the credibility of the news organisation. It will be important for journalists and newsrooms to carefully fact check any articles written with the help of AI, to ensure the accuracy and integrity of their reporting.

4.Generating Headlines If you are doing A/B testing, challenge yourself with your headlines vs those of the AI. You can ask it to make the headline funny, negative, or positive, remove the jargon or use a specific number of words. Shame that ChatGPT really struggles with maths – always count the words in the final result and ask it to rewrite it if it makes a mistake (it almost certainly will).

5.Translating articles into different languages Like any other AI-powered translation tool, it is very approximative and you will have a few good laughs along the way. However, it can come in handy if you need to get a general sense of the text in a different language. If you want to get something a bit more accurate, you better stick with Google Translate.

6.Generating Email Subjects and Writing Emails Outsourcing one of the most tedious office tasks to a machine sounds like a dream. ChatGPT can speed up the process of emailing your sources or colleagues as you can generate a sound message with one swift prompt. Just fill in the blanks and send it away. A genuine time-saver. But remember, you will need to edit the final version.

7.Generating Social Posts. Like emails, posting on socials is useful but terribly time-consuming. You can ask ChatGPT to write a tweet or a LinkedIn post on a topic, freeing

your time and brainpower for more worthwhile writing.

8.Provide Context for Articles You can ask ChatGPT to give you context about a news story, say, why members of the UK rail unions are on strike this year, and it can find

quite accurate information. But the usual warning applies: double-check everything. It can also explain how something works, which can be useful if your piece needs a short explainer in plain language Kunova’s excellent guide was a much needed resource for journalists and particularly useful coming at a time when the fear around AI had reached

a bit of a fever pitch. More articles of a similar vein followed, because of course, ChatGPT is just one of the many AI tools in the journalism landscape. Generative AI can be used in several other ways too, especially in our swiftly evolving world of multimedia.

9.Image Generation Generative image models like DALL-E 2 and Stable Diffusion could deliver custom stock photos to newsrooms that cannot afford subscriptions

to photo services. These tools have also allowed users to generate realistic images based solely on text prompts. Some technology-focused reporters have already begun using AI-generated images to illustrate their stories, more as a gimmick than anything else. But as these technologies continue to improve and enter the mainstream, they

are likely to reshape newsroom debates over photo manipulation, photo illustrations, and misleading stock photos.

10.Transcribing Interviews The latest automatic speech recognition models will allow reporters to easily and accurately transcribe their interviews for free. Many journalists already upload their interviews to paid auto-transcription services like Otter and Trint, which rely on machine learning models to quickly produce fairly accurate transcriptions. The Whisper model, released by artificial intelligence company OpenAI in September, is even moreaccurate, doesn’t require an internet connection, and is completely free.

11.Other Multimedia Generative AI is becoming pretty handy in the generally timeconsuming world of multimedia production. Descript — an audio and video editing app that got investment from OpenAI largely relegated to paid notices from relatives. And as this information dries up, citizens feel more estranged from the agencies that govern their lives and the officials who set their tax rates and hire their superintendents.” If this commodity news can be automated by AI, we can provide a lot more information — much of it useful, if not sexy — to people who need it.

In NiemanLab’s Predictions for Journalism 2023, Joe Amditis, assistant director of products and events at the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University, offers his two cents: that this kind of new tech could impact small- and mediumsized local news organisations — particularly those with fewer than five full-time people on staff. Cecilia Campbell, chief marketing officer,

United Robots echoes this, predicting that local outlets will now embrace “the opportunities the tech offers to increase the breadth of topics and the number of stories they can cover, and the size of the audience.”

AI’s advantages could save independent and hyperlocal news publishers an incredible amount of time and effort. The ability to quickly generate documents, instructions, guides, and various elements of internal infrastructure, generating summaries of public meetings and documents, creating tweets and social posts from news stories, drafting scripts for news broadcasts, even suggesting different headline variations — all at the click of a button — would be a game-changer for news organisations that are already strapped for people and resources. The same thing goes for generating invoices, public records requests, and even basic outreach emails.

Amditis has created a new ebook called the Beginner’s prompt handbook: ChatGPT for local news publishers. In the book, he has included dozens of possible use cases for local newsrooms, a step-by-step breakdown of the anatomy of a ChatGPT prompt, and beginner, intermediate, and advanced prompts for local publishers.

He sees many advantages: not only does AI free up time for journalists to report or engage with community members, it “could also help make local news content more accessible to people with disabilities, people who speak English as a second language, and people who might not usually come across local news stories in their current format”.

AI FOR COST EFFICIENCIES

Granted, this is an area where things get a little uncomfortable when speaking about AI and the impact on media, but a number of publishers have, understandably perhaps, started touting the cost-saving potential of the new technologies.

Gannett has made investments in AI and machine learning tools to simplify routine tasks, such as selecting and cropping images quickly, personalising content and gathering datasets to inform readers on where to watch various sporting events. Doug Horne, CFO at Gannett, said during the company’s earnings call earlier this year that this is to achieve an annual savings of atleast $220 million this year. AI will be used to “create efficiencies”.

The Arena Group recently announced partnerships with AI firms like Jasper and OpenAI “to give our reporters and editors the ability to quickly and efficiently search and pull content from our rich archives for news stories,” said Ross Levinsohn, CEO of The Arena Group. Levinsohn noted “productivity improvements” since testing the use of generative AI. When The Wall Street Journal reported in February that The Arena Group was using AI to produce articles, shares jumped 18%.

“We do not intend for this to replace our talented writers and editors. But we do believe this initiative will make our great teams even more productive.

These are just a few of the examples of how we are proactively adjusting our cost structure to ensure that we hit our 2023 adjusted EBITDA target,” Levinsohn said.

Similarly, earlier this year the German media group Axel Springer said journalists are at risk of being replaced by artificial intelligence systems like ChatGPT. According to The Guardian, the announcement was made as the publisher sought to boost revenue at German newspapers Bild and Die Welt and transition to becoming a “purely digital media company”. It said job cuts lay ahead, because automation and AI were increasingly making many of the jobs that supported the production of

their journalism redundant.

“Artificial intelligence has the potential to make independent journalism better than it ever was – or simply replace it,” CEO Mathias Doepfner said in an internal letter to employees.

Axel Springer did not specify how many of its staff could be cut, but promised that no cuts would be made to the number of, “reporters, authors, or specialist editors”.

USING AI FOR REVENUE OPPORTUNITIES

BuzzFeed’s Peretti said AI-powered content will move “from an R&D stage to part of our core business” in the company’s earnings call on March 13. BuzzFeed president Marcela Martin outlined how BuzzFeed’s AI-powered Infinity Quizzes are the beginning of the company’s adoption of AI “to enhance the audience experience and open up new avenues for monetisation”. A custom quiz matching a reader with a house plant was sponsored by Scotts Miracle-Gro.

But on the content creation side, AI tools were recently integrated into BuzzFeed’s content management system, meaning more writers now have access to produce AI generated content, indicating that the scalability is really just starting now. Peretti also said AI technology can help automate, improve and streamline the process of making animated content.

AI AND NEW JOBS AND POSITIONS AROUND AI

Everybody is talking about the artificial intelligence behind ChatGPT. But less widely discussed is a jobs market mushrooming around the technology, with some newly created roles paying upwards of $335,000 a year. For many of these, a computer engineering degree is optional.They’re called “prompt engineers,” people who spend their day coaxing the AI to produce better results and help companies train their workforce to harness the tools.

As the technology proliferates, many companies are finding they need someone to add rigour to their results. “It’s like an AI whisperer,” says Albert Phelps, a prompt engineer at Mudano, part of consultancy firm Accenture in the UK. “You’ll often find prompt engineers come from a history, philosophy, or English language background, because it’s wordplay. You’re trying to distill the essence or meaning of something into a limited number of words.”

Companies like Anthropic, a Googlebacked startup, are advertising salaries up to $335,000 for a “Prompt Engineer and Librarian” in San Francisco. Automated document reviewer Klarity, also in California, is offering as much as $230,000 for a machine learning engineer who can “prompt and understand how to produce the best output” from AI tools.

In an earlier section in this chapter we also covered how the Financial Times had appointed its first ever AI editor Madhumita Murgia. Though that’s an entirely different type of role, focused on leading coverage of AI as technologies progress and find application in more and more fields, it’s an indica tor of the type of new roles that may emerge in other news organisations.

LIMITATIONS AND DISADVANTAGES OF GENERATIVE AI

First and foremost, there is no concept of truth.

Truth is not the goal. OpenAI is open enough to say that there is no source of truth in ChatGPT. Their limitations

section covers it: “ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers. Fixing this issue is challenging, as:

(1) during RL training, there’s currently no source of truth;

(2) training the model to be more cautious causes it to decline questions that it can answer correctly; and

(3) supervised training misleads the model because the ideal answer depends on what the model knows, rather than what the human demonstrator knows.”

And ask OpenAI’s playground itself on whether the machine can tell the difference between truth and fiction: “GPT-3 and ChatGPT do not have a ground truth reference, so they cannot tell the difference between truth and fiction. However, GPT-3 and ChatGPT are trained on a large corpus of text, which can help them make informed guesses about the plausibility of a given statement.”

ChatGPT is proof that finding “truth” is a lot trickier than having enough data and the right algorithm. Despite its abilities, ChatGPT is unlikely to ever come close to human capabilities: its technical design, and the design of similar tools, is missing fundamental things like common sense and symbolic reasoning. Scholars who are authorities in this area describe it as being like a parrot; they say its responses to prompts resemble “pastiche” or “glorified cut and paste”. As Jenna Burrell writes in a piece for Poynter, “when you think of ChatGPT, don’t think of Shakespeare, think of autocomplete. Viewed in this light, ChatGPT doesn’t know anything at all.”

Time limit Equally importantly, there is a datecut- off. If you push ChatGPT hard enough about current developments, it will repeat one line back to you — that its training cut-off date is 2021. Try asking ChatGPT, “Did Kari Lake win in Arizona” and you’ll see what I mean. Since that election happened in 2022, ChatGPT does not “know” about it. This means that, while it could be helpful in synthesising information, making edits and informing reporting, FT’s Murgia, speaking to Reuters Institute, believes generative AI as we

see it today is missing some key skills that will prevent it from taking on a more significant role in journalism. “Based on where it is today, it’s not original. It’s not breaking anything new. It’s based on existing information. And it doesn’t have that analytic capability or the voice,” she says.

Sourcing limitations AI opacity means sourcing is a deadend. ChatGPT does not cite all its sources when it generates text. This is how large language models work. For journalists, sources, and sourcing always matter. OpenAI has not posted a list of all its training sources for ChatGPT. There are some guesses floating around. So why trust a talking tool that is opaque?

When working with tools like ChatGPT, keep in mind that it is smart, but not that smart. It is a machine that has no intentions — it does not want to help or mislead you; it has no concept of what is real and no morals. It is just what it says on the tin – it generates text based on a lot of information it has been trained on.

Potentials of misinformation, disinformation and AI misuse Because of this, you need to fact-check absolutely everything it generates. It goes beyond what you would need

to verify if the text was written by a human: ChatGPT will almost always answer your question and if no real information is available, it may make one up. Factcheck maths, names and places and always make sure that everything, well, exists. Data produced is well-written, convincing, and often entirely incorrect. Producing disinformation

like this has suddenly become vastly cheaper than it was just a few months ago, and with no marginal cost to produce this content, there is likely to be a massive spike in its production. As Josh Schwartz, CTO of Chartbeat tells NiemanLab, “Trustworthy journalism that can find a way to drown out the noise has never been more important, or more challenging.”

But wildly cheap-to-produce disinformation isn’t the only threat the media faces, Schwartz adds. Wildly cheap correct information has the potential of being just as disruptive, rivalling the content produced by many SEO-focused sites. “Will there be any place at all for human-written SEO-friendly content?” he asks. “It seems likely that the market

for it will be massively smaller, as it struggles for position in search results against a broad set of algorithmically generated content.”

Another potential risk of relying on large language models to write news articles is the potential for the AI to insert fake quotes. Since the AI is not bound by the same ethical standards as a human journalist, it may include quotes from sources that do not actually exist, or even attribute fake quotes to real people. This could lead to false or misleading reporting, which could damage the credibility of the news organisation. It will be important for journalists and newsrooms to carefully fact check any articles written with the help of AI, to ensure the accuracy and integrity of their reporting.

While generative image models like OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 and Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion have allowed users to generate realistic images based solely on text prompts, they are likely to result in instances of photo manipulation, inaccurate photo illustrations, and misleading stock photos.

Propaganda and disinformation are also possible issues. Cory Bergman is a co-founder of Factal, and he tells NiemanLab: “Imagine using ChatGPT to spam human-like comments and social media posts that support an agenda. Or a war. Thinking of running for office? Time to mobilise the AI content army.”

Ethical concerns around plagiarism We already know that large language models, such as GPT-3, have the potential to disrupt newsrooms by enabling journalists to use AI to write their stories. However, this raises ethical questions around authorship and plagiarism. If a journalist relies too heavily on AI to write their stories, who can be credited as the author?

Additionally, there is the potential for the AI to inadvertently plagiarise other sources, raising questions about journalistic integrity and accuracy. Since the AI can write in a variety of styles and lengths, its content is virtually indistinguishable from an average human writer. OpenAI is currently working on creating a digital watermark embedded in ChatGPT responses, but that may not solve the issue entirely.

Appropriating the open web Further, there are substantive ethical questions about trawling the open web and using the creative expression of humanity (even if all the text was uncopyrighted) this way for generative machines. It’s one thing for the collective commons to be open to humanity. It’s another thing for it to be used for massive computational pattern-matching models to get machines to blindly mimic humanity. And it comes as no surprise, for example, when Getty Images sued Stability AI (image generative AI) for copyright infringement in London.

In this interview published by the Tech Policy Press on an indigenous perspective on generative AI, Michael Running Wolf (North Cheyenne man, computer science PhD student, and former Amazon engineer) says this: “It’s a lie to say that it only costs electricity to generate the art. That’s a lie. These Stable Diffusion could not

do this if they didn’t have the ability to scan the intellectual property of the internet. And that is worth something.”

It all boils down to where AI gets its stuff from. Even the best generative AI tools are only as good as their training, and they are trained with data from today’s messy, inequitable, factually challenged world, so bias and inaccuracy are inevitable. Because their models are black boxes, it is impossible to know how much bad information finds its way into any of them. But considering that more than 80% of the weighted total of training data for GPT-3 comes from pages on the open web — including, for example, crawls of outbound links from Reddit posts, it is highly likely that information generated is problematic at best, and dangerous at worst. Since the tool has been trained on what humans, past and present, have written about groups like women or minorities, information generated could also be biased, even though it has reportedly been trained

not to give sexist or racist answers.

So are journalists becoming redundant? AI-based tools will never replace human journalists. As we know, CNET recently made the mistake of overestimating AI’s ability, yielding not only a series of articles rife with factual errors but a broader reckoning for the company and perhaps the industry at large. If AI replaced humans, which it would do ineptly, it would merely flood the internet with even more unreliable (but plausible sounding) junk.

The fear that journalists will become redundant is also fuelled by journalism itself, as Burrell points out. Headlines like this one from The New York Times: “Meet GPT-3. It Has Learned to Code (and Blog and Argue) fuel this idea. Even articles meaning to serve as correctives fall into anthropomorphism, like a piece in Salon that said “AI chatbots can write, but can’t think.” According to Burrell, the claim that ChatGPT can “write” is an exaggeration, an inflation of the tool’s capabilities that contribute to further misunderstandings and overstatements. Memo’s Kim believes that a company that uses AI to analyse new articles, believes that it’s the evergreen and informational content

that will be most at risk. “The power of the editorial publishers will endure.

So much of the product that premium publishers offer is their masthead and authority. The same words living elsewhere simply don’t carry the same weight or prominence,” Kim told Euronews. However, much like previous technological advancements, tools like GPT could be part of a broader shift and redelegation of how journalism is done and change how reporters do their jobs — freeing them up to spend more time interviewing sources and digging up information and less time transcribing interviews and writing

daily stories on deadline.

AI isn’t taking over a journalist’s role but making their job easier. They should be seen as TOOLS rather than pieces themselves. “It’s probably better to think of these tools as internal newsroom tools, making suggestions to reporters and editors rather than generating text that will be directly published,” says Nicholas Diakopoulos, associate professor of communication studies and computer science at Northwestern University, in a piece for NiemanLab. “Research is blazing ahead to make future versions of

the technology better able to output factually accurate text. And news organisations could also invest more in R&D to fine-tune and further adapt the models to be better aligned to journalistic needs.”

The fear of bots replacing journos is perhaps unfounded. However, interfacing with an artificial intelligence will become a specialised skill. Just as “Social Media Editor” was a wholly unique job title, new roles may well be invented and defined by a new class of journalists who will leverage this technology in ways we can’t predict. Publishers are in the driver’s seat ChatGPT is just a tool – albeit a brand new, powerful tool with huge scope, but a tool nonetheless. It does not change the guiding principles of journalism – a fundamentally human activity. Publishers have to work on certain aspects:

1.Transparency

AI written articles could have a byline which makes it unequivocally clear that it was written by a robot, not a reporter. Transparency is critical internally as well as externally, and key for trust. In the case of the CNET story, the Verge reports that there seems to be a lack of transparency around the actual purpose of the content too. According to the Verge, the business model of CNETs relatively new owners Red Ventures, is about creating content designed to get high rankings in search, and then monetise the traffic.

Will AI labels/transparency work? Doesn’t transparency demand that news organisations using machines to write stories disclose that to users? This finding only brings up a tension between the risk of labeling and the assumptions of the reader. It may only further drive publishers to be resistant to label AI-generated news text as such.

Binary disclosure, then, won’t cut it, according to Subramaniam Vincent, Director of Journalism and Media Ethics at Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. “The real question for news readers and publishers is not plain disclosure in a binary sense: Written by human vs. written by generative AI,” he writes. “Transparency has to be along AIliteracy lines among the public, beyond simplistic labels. We may need a deep transparency of models, training data corpora, and model limitations to the reader, in plain de-complexed language.”

2.Trust

Trust is the currency of journalism. Any deployment of new tech tools must in no way leave room for people to question the integrity of a publication. In mid-2022, AI news

headlines were tested with people. Foretelling how the public at large may treat generative AI news writing was some research that came out about six months before OpenAI released ChatGPT. In their work studying how people perceived news generated by AI, a group of researchers (Chiara Longoni, Audrey Fradkin, Luca Cian, and Gordon Pennycook) pointed out that if it were disclosed that a headline was AI-generated (a form of labeling), readers attached an additional credibility deficit to the news. If

journalists start using generative AI for news writing, then, the so-called trust deficit may get another wheel to accelerate on.”

º

One way to address this trust deficit, according to Jennifer Brandel, CEO of Hearken, is to care. She asks that journalists orient their interactions to ensure the people they engage with, report on and report for, get the signal that the journalists and the newsroom really care. Brandel lays down three questions she believes journalists should ask themselves more in 2023:

- Are you aware of the power you wield in a situation, based on what identities you carry with you or are perceived to have?

- Do you consciously work to ensure the people you’re interviewing feel truly heard and understood? Or are you rushing in to grab a quote and leaving them in the dust because: deadlines?

- Did the people you reported on feel like you got it right in the end? How do you know?

“It’s easy to forget that every interaction that journalists and other newsroom staff have with the public — be that sources, readers, viewers,

members, subscribers, commenters, etc. — is an opportunity to influence people to feel something,” she says. That’s where AI can never replace the human touch.

In the latest edition of his newsletter, The Rebooting, Brain Morrissey too reckons that AI will displace a lot of work that’s mundane communication

and will end up putting a premium on the human connection. “We’re hard wired to trust humans more than machines. There’s a reason we tend

to get far more frustrated trapped in a loop with automated customer service. Publishers that have both human connections and the ability to convene a community will be far more valuable.”

Professor Charlie Beckett, of the Polis/ LSE JournalismAI research project, speaking to Reuters Institute, also advises caution and would discourage journalists from using new tools without human supervision: “AI is not about the total automation of content production from start to finish: it is about augmentation to give professionals and creatives the tools to work faster, freeing them up to spend more time on what humans do best,” he says. “Human journalism is also full of flaws and we mitigate the risks through editing. The same applies to AI. Make sure you understand the tools you are using and the risks. Don’t expect too much of the tech.”

So what should media organisations keep in mind about AI? Mattia Peretti writes in LSE blogs…

1- The Need for Strategy

We talk about “implementing AI” as if it was one single process. But the reality is that depending on one’s use case and the type of technology (AI is an umbrella term with many subfields), that process may be completely different from the one one has to go through for a different use case.

Using a machine learning model to filter the comments you receive from your readers, automatically tagging potentially harmful ones, for example, requires a completely different process than if you want to optimise your paywall to maximise your chances to turn a sporadic reader into a paying subscriber. It is key to come up with a strategy.

- Tools: Buy or Build?

“Using AI” means using some technological tools that can help one’s work as a journalist. So the question is, where does one get those tools? The debate in the industry lies mostly around the dichotomy buy vs build: Does one build AI tools in-house to serve your specific purpose or does one instead buy existing tools and adapt them to one’s needs?

Famously, two international news agencies that have been at the forefront of AI innovation have taken different approaches: Reuters builds most of its AI tools in-house, while the AP buys tools by working with startups and vendors in the open market. Organisations have to consider what they are trying to do, evaluate the costs of both options, consider carefully what skills they already have in the team or what they can easily acquire, and chart a path that works for them.

If they do decide to build, it’s likely that there are others in the industry who went down that route already and that they can learn from. And if they decide to buy existing tools, there are many available out there. The buy vs build dichotomy is a false one.

There’s a third route, which is to partner with startups or academic labs that may have the skills one needs, have done a lot of useful research already, and could be eager to partner with media to apply their theoretical learnings to a practical use case. - Collaboration is Essential

When it comes to AI, collaboration is key. Someone in another news organisation may be facing the same challenges and may be trying to build the exact same thing.

JournalismAI, for instance, has helped news organisations from across the world collaborate on AI projects. One team, with members from Bloomberg News, CLIP, DataCritica, and La Nación, went about using artificial intelligence to identify visual indicators within satellite imagery to chase a story, hoping their tool could be used to identify illegal airstrips built in a remote area or the expansion of deforestation in a jungle or even being able to prove if a public road was indeed being built.

Another, with Abraji (Brazil) and Data Crítica (Mexico) as participating organisations, sought to train a language model to detect hate speech – in Spanish and Portuguese

– directed primarily at journalists and environmental activists.

A third, with participating oganisations Sky News (UK), Infobae (Argentina), Il Sole 24 Ore (Italy), The Guardian (UK), focused on tracking influencers, to help journalists to investigate influencers on a greater scale using AI techniques and developing a replicable methodology. This project focused on creating a system to flag Instagram users who

were promoting brands or services without complying with the rules of disclosing they have — potentially — a commercial relationship

INITIATIVES THAT HELP JOURNALISTS BUILD SKILLS ON AI

Journalists can report on AI much better if they know how to use it — and they will be much more responsible in using it if they understand the risks and potential consequences.

There are more and more journalists doing fantastic work on algorithmic accountability, and initiatives like the AI Accountability Network of the Pulitzer Center are allowing more reporters to build their skills for this critical purpose. This Network seeks to address the knowledge imbalance on artificial intelligence that exists in the journalism

industry, especially at the local level and to build the capacity of journalists to report on this fast-evolving and underreported topic with skill, nuance, and impact. JournalismAI — a research and training project at Polis, the international journalism think tank of the London School of Economics — also helps news organisations use artificial intelligence (AI) more responsibly.

This can be done best once journalists and media organisations understand how AI works via direct experience. Teams like the AI and Automation Lab of Bavarian Radio in Germany are positioning themselves as leaders in this field because they have been smart enough to recognise this, creating a team, a dedicated lab, that is responsible for both using AI for product development and for algorithmic accountability reporting.

FINAL THOUGHTS

We’ll level with you — it’s not been easy putting together this story on generative AI because every week brings about five new developments and interesting articles about publisher experiments and other assorted uses for the new tech. And that’s not even factoring in all the material now coming in, at the time of writing, about new higher iterations of the technology such as GPT-4 which The New York Times has called “exciting and scary”. As we mentioned earlier, our chapter on AI for this book last year

was a very different read indeed! And who knows what may come around by next year. As we all contemplate the waves of change ahead, we leave you with this quote from Mattia Peretti: “I invite you to be balanced in approaching AI. Be skeptical, understand the limitations of the technology and its risks, and be careful and responsible once you decide to use it. But while you do all of that, allow yourself to get excited for the opportunities that it opens up.”

THE Innovation in News Media World Report is published every year by INNOVATION Media Consulting in association with WAN-IFRA, The report is co-edited by INNOVATION President, Juan Señor, and Senior Consultant Jayant Sriram