20 May NEW TECHNOLOGY: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

We are living in a time where foldable smartphones and tablets are a reality, where people regularly speak to their devices, where someone can appear by hologram for an interview, and where automated decision making by machines is so complex that even their creators struggle to understand the processes.

Publishers have to strike a balance between not being left behind by technology, and not being continually distracted by the latest “bright, shiny things,” as stressed in a recent report from the Reuters Institute. Here we take a look at the tech developments that news publishers should be watching and experimenting with.

Robot Journalism

‘Robot journalism’ refers to a method of journalism where at least part of the work of writing an article is done by a machine. It has been around for the last decade, but it is now becoming more widely embraced, no longer attracting the level of horror that it once did about journalists’ jobs being stolen by algorithms. (Although the authors of a WAN-IFRA report on automated journalism believe that AI and ‘robot journalism’ still have a hype problem and that we should see the automation process as a logical extension of the Industrial Revolution.)

The classic use of AI in journalism production is algorithms rewriting structured data into a narrative using natural language generation (NLG). The Associated Press for example, has been using Automated Insights’ NLG tool, Wordsmith, since 2014, to produce articles on companies’ quarterly earnings reports. Automated writing remains primarily in the creation of business news and sports.

RADAR was launched in September 2017 as a joint venture of the U.K.’s Press Association and startup Urbs Media. As Politico explains, RADAR reporters root around public data sets until they find something interesting, then they might do some extra research and conduct interviews to obtain quotes.

They then write a template, which includes some analysis, and based on this, their NLG software can produce hundreds of localized articles based on data from the chosen set. For example, stories could cover how often ambulances in different parts of the U.K. are delayed, and how these levels compare to the national average. RADAR’s five reporters and two founders produce roughly 8,000 stories per month.

Forbes, for example, which has a large network of contributors, is rolling out a new content management system that will suggest topics for contributors to write about, based on other content they have produced, providing links, images and headline suggestions. The company is also testing an AI writing tool that aims to produce pieces that journalists or contributors will just be able to polish and add final touches.

According to Digiday, these new tools are not designed to produce something that a contributor or reporter would feel comfortable publishing as it is, but to act as a thought-starter. Digiday also reported that the site had doubled the number of loyal visitors it attracts every month since rolling out the new CMS in July 2018, and that traffic has increased as well.

Whenever such ‘robo-journalism’ initiatives are described, their advocates go to great lengths to stress that they are not trying to replace journalists, and that robots aren’t the journalists of the future. As Politico noted, “Computers are still far from being able to develop sources, provide high-level analysis or infuse a narrative with character and colour.” AI will “augment, never replace the work of the worlds’ journalists,” said the AP’s business editor Lisa Gibbs at a Google News Initiative Innovation Forum in December 2018, calling for a common set of standards and best practices for AI in news.

The journalist’s assistant

AI and automation can also help journalists with several tasks aside from writing, from the reporting phase to distribution. For example:

• The Quartz AI Studio, established in November 2018 with funding from the Knight Foundation, aims to help journalists use machine-learning methods to publish stories that would otherwise be impossible to cover, because they may involve identifying patterns in thousands of documents or searching through millions of images. The idea, according to Journalism.co.uk, is that the machine-learning tools available via the platform will be able to help journalists analyse data even if they have no coding or maths skills.

As the 2019 Journalism, Media and Tech Trends Report from Amy Webb’s Future Today Institute (FTI) notes, computational journalism techniques are taking computer-assisted reporting, which has been used in investigative journalism for some time, to the next level, with algorithms able to detect connections in data sets that a human would never have been able to find.

• The AP is experimenting with automation and AI, “to eliminate routine work like video transcription, so that our journalists can focus on doing the creative and curious work,” business editor Lisa Gibbs explained. It is also building a tool called Verify which will allow journalists to more quickly vet images and video on social media, by analysing metadata to check out the source, breaking down videos into separate frames and searching to see if they have been posted before in different contexts.

• Getty Images launched ‘Panels’ in August 2018, a tool that uses AI to analyse the text and content of a story before suggesting pictures to go with it. According to Journalism.co.uk, it was developed by working with newsrooms, and uses a “self-improving algorithm” that learns how an editor selects an image and optimises its performance over time. Speaking to Adweek, Andrew Hamilton, Senior Vice President of Data and Insights at Getty Images, was keen to stress that the tool wasn’t trying to replace a photo editor, but rather to make their job easier. “We’re leaving the editor to tell that story,” he said.

• Tools such as Wochit or Wibbitz can automate much of the process of creating a video based on an article or script from a journalist. Using Wochit, for example, the journalist retains creative control, but its ‘predictive’ platform aims to make putting videos together straightforward and intuitive, as its website explains.

Voice-activated smart speakers

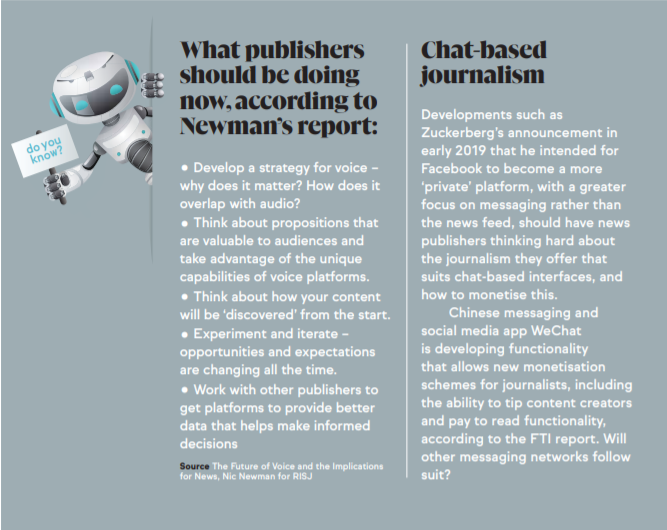

We are in the stage of ‘over-hype’ for voice-activated devices or smart speakers, says Nic Newman, who wrote a report on the implications of voice for news for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford. But rates of ownership of voice-activated speakers are growing, Newman’s report found: faster than smartphones at a similar stage of adoption. This trend doesn’t just include ‘home’ devices, such as the market leader Amazon Echo, but also smart headphones or in-car assistants.

The 2019 Journalism, Media and Tech Trends Report from Amy Webb’s Future Today Institute (FTI) predicts that ‘digital assistants’ such as Amazon’s Alexa or Google Assistant will only become more ubiquitous.

Furthermore, of those who do use them many seem to love them, both because of their speed and usefulness, and because they are seen as fun and providing the thrill of feeling futuristic, Newman found while conducting research. Voice technology can allow users to get away from looking at screens, and to ‘de-clutter’ in a world where they might feel surrounded by devices and remote controls.

However, they are not as widely used or valued for news as publishers and broadcasters might hope, Newman’s report found. Playing music was the most used and valued activity among the smart speaker owners surveyed. While 21% of owners did access news updates daily, news was not widely valued by users.

The main reasons respondents gave for their lack of news consumption were that the content, tone and length of updates weren’t right, that is was difficult to discover content, and that they just didn’t need to use it as there were so many other ways they could find news.

The BBC dominates consumption on U.K. smart speakers: as the default news provider on many devices, it is at a huge advantage, as many people don’t bother changing this. And this is related to an aspect of this kind of audio news consumption that worries some news organisations – it isn’t anywhere near as easy to find information from a range of sources via smart speakers as it is when using screen-based devices.

Interestingly, passive radio listening is far more popular than podcasts on smart speakers, likely a reflection of the fact that smart speakers tend to be used in the home for background listening, and that they are currently disproportionately owned by older people, whereas more younger people listen to podcasts.

Google News launched a new experiment in December 2018 meant to deliver more personalised audio news feeds through Google

Assistant, “bringing the artificial intelligence of Google News to the voice context of the Assistant,” according to a blog post from the company. Each story is an individual chunk, rather than part of a longer briefing, so that when a user wants news, they can be offered a selection of stories from different news providers. When a user asks for news, Google Assistant provides a personalised audio news playlist “assembled in that moment.” It focuses on topics that it believes the user cares about, it won’t repeat stories that have already been heard, and the user can ask to skip a story or go back.

It is important to consider, as the Future Today Institute report suggests, “if Amazon and Google control the means of our future conversations, how will news and media brands be included and prioritized?”

Blockchain

Blockchain, which first entered into public consciousness in connection to cryptocurrency Bitcoin, broke into the mainstream in 2017 as, “a revolutionary way to share and store information,” according to the Future Today Institute’s report.

The implications of blockchain for journalism are still far from clear, however. A report on media startups using blockchain, from Mattias Erkkilä at LSE’s journalism and society think tank, Polis, found that the most common journalism-related uses of blockchain were:

- Saving content metadata on the blockchain

Creating an open and immutable record of content origin, publishing time and editing history that can be used to counter content that falsely claims to originate from a certain source and building trustworthiness among consumers.

- Enabling user participation

Blockchain can be used for identity management, event logging and contractual management.

- Enabling an easier funding model for the company through cryptocurrencies.

“A strive for decentralization is a recognized characteristic of the blockchain movement and it might well be more important than the technology itself,” Erkkilä wrote.

Civil is the key example of a journalism blockchain startup, but its progress hasn’t been straightforward. It is based on the idea of creating a community-run platform for independent journalism, using “decentralization and network effects to offer an alternative model that can support trustworthy journalism and help fulfil the information needs of citizens,” according to founder Matthew Iles.

Both newsrooms/journalists and members of the public can buy tokens to become a member of Civil. The tokens represent a member’s voting power within the Civil Registry and elsewhere on Civil. Members can use their tokens to vote and challenge unethical newsrooms on the Civil Registry, and their tokens can’t be taken away by any company.

Newsrooms that join Civil will have the ability to index and permanently archive their content to the blockchain using the Civil Publisher, and be able to accept direct, peer-to-peer payments from members who wish to support them. An editor of one of the newsrooms involved wrote that the blockchain technology, “provides the strongest protection that technology can give speech rights and press freedom.”

As John Keefe, technical architect for bots and machine learning at Quartz, wrote for a piece published by Nieman Journalism Lab in 2019, it is very complicated and timeconsuming to get involved by buying tokens, unless you happen to be an experienced cryptocurrency trader.

Going forward, a distribution channel leveraging blockchain technology could be used to prevent censorship and to ensure access to information, while guaranteeing that content doesn’t get altered, according to the FTI report.