04 Mar Visual Investigations

Best Practice in Osint and Journalism

YOU’VE OFTEN HEARD THE ADAGE a picture can tell a thousand words. Take this idea and supercharge it: imagine a narrative made up o millions of images and video recordings from satellites, smart phones and data tracking devices of every kind now available. That is the power of visual investigations, one of modern journalism’s

most exciting new fields. Pioneered by the New York Times, the investigative journalism group Bellingcat and others, this is a medium that combines cutting

edge digital forensic techniques with the ethos of “community journalism”, piecing together images and videos recorded by multiple sources to reconstruct an event. This isn’t just building a story or narrative, the effect of such journalism is the visual demonstration of truth.

As video technology grows more and more sophisticated, as deep fakes and the state and private actors who propagate them proliferate, this is how journalism can hit back and gain the upper hand of credibility. The examples of visual investigations we discuss in this chapter are all as inventive as they are pioneering and function as guides for delivering high quality work across platforms.

THE NEW YORK TIMES Started in 2017 and now numbering 17 staff members, The Times’ visual investigations unit is one of the publisher’s most dynamic new departments. It was responsible for one of the more striking pieces of journalism from the Ukraine war and featured intercepted radio transmissions from Russian soldiers indicating an invasion in disarray. The radio transmissions, where soldiers complained about a lack of supplies and faulty equipment, were verified and brought to life with video and eyewitness reports from the town where they were operating. It was the work of the investigations unit that specialises in open-source reporting, using publicly available material like satellite images, mobile phone or security camera recordings, geolocation and other internet tools to tell stories. These sort of pieces can also be experiences; The Times used security and cellphone video, along with interviews, to tell the story of one Ukraine apartment house as Russians invaded.

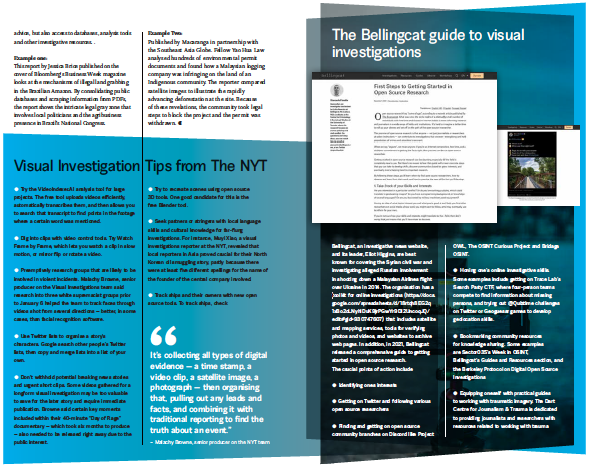

“There’s just this overwhelming amount of evidence out there on the open web that if you know how to turn over the rocks and uncover that information, you can connect the dots between all these factoids to arrive at the indisputable truth around an event,” said Malachy Browne, who leads the Times’ team.

Another prominent example is The Times’ “Day of Rage” reconstruction of the Jan. 6, 2021 Capitol Riots in the U.S. that has been viewed nearly 7.3 million times on YouTube. The 40-minute piece is meticulous. Composed mostly of video shot by protesters themselves, in the heady days before they realised posting them online could get them into trouble, along with material from law enforcement and journalists. It outlines specifically how the attack began, who the ringleaders were and how people were killed.

Speaking at an expert panel on the rapidlyemerging field of visual investigations at the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference in 2021,

Browne emphasised that traditional reporting methods like interviews, research, and data requests remain at the heart of their approach.

“It’s collecting all types of digital evidence — a time stamp, a video clip, a satellite image, a photograph — then organising that, pulling out any leads and facts, and combining it with traditional reporting to find the truth about an event,” he said.

Browne added that, in a time of misinformation and media mistrust, video forensic projects can build public trust by transparently showing both the events and the reporting process.

Other prominent projects by the NYT team have also explored the botched, lethal US drone strike in Afghanistan and Israeli airstrikes in Gaza that killed 44 people.

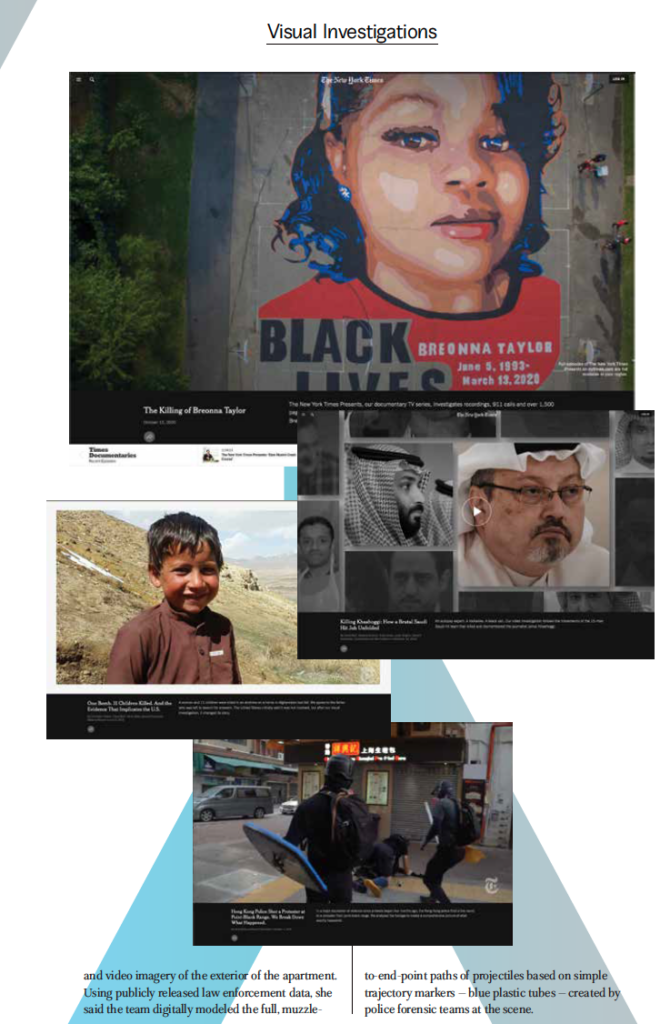

A particular example highlighted at the conference was the police killing of a young African American woman, Breonna Taylor, inside her home in 2020. None of the seven police officers at the scene had worn body cameras, and reporters were barred from accessing the apartment. Yet the visual investigations team at The Times was able to tell the story of the 32 bullets fired anyway — and show the police officers’ culpability — with detailed 3D reconstructions and a momentby- moment timeline.

Describing the investigation, unit reporter Anjai Singhvi told the conference the team found several workarounds when direct access was blocked by law enforcement. For instance, they tracked down a 360-degree layout of an apartment nearly identical to Taylor’s in the same building on a real estate portal. In addition to reviewing many hours of police interviews, her colleague Browne traveled to Louisville, Kentucky, and captured still- and video imagery of the exterior of the apartment. Using publicly released law enforcement data, she said the team digitally modeled the full, muzzleto- end-point paths of projectiles based on simple trajectory markers — blue plastic tubes — created by police forensic teams at the scene.

WASHINGTON POST Although still in its nascent stages, the field of investigative storytelling is growing rapidly. The Washington Post announced recently that it was doubling the size of its video forensics team, in the first expansion since the team was launched in the summer of 2020. The new roles open up six positions for two video reporters, a motion graphics reporter, an investigative researcher, a senior video producer and a designer. The expansion aims to bolster The Post’s capacity to explore and experiment with video reporting to power both short and long term investigative stories told in a myriad of ways, across mediums. The team uses open-source, widely available materials, social

media videos and photos, Google Maps, public databases and weather reports, or high-quality satellite images offered through paid subscriptions.

The Post’s Visual Forensics department captures and provides context around the firehose of visuals available on the ground and on the internet. “With an expanded team, we will be able to work on multiple stories simultaneously and increase our ability to respond to breaking news.” Kat Downs-Mulder, Chief Product Officer and Deputy Managing Editor at The Post, told WAN-IFRA.

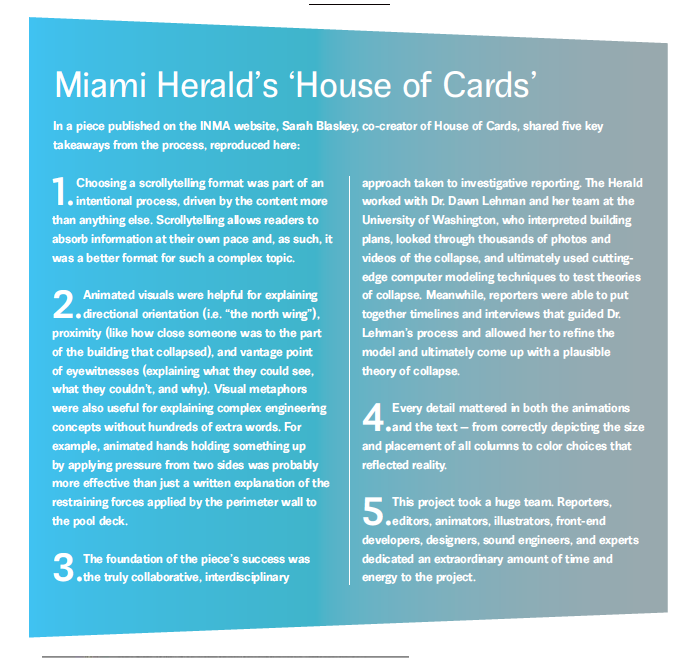

THE MIAMI HERALD In June 2021, 12-story condo building Chaimplain Towers South, collapsed in the middle of the night, killing 98 people in South Florida. The Miami Herald conducted a meticulous journalistic investigation of the event in a piece called House of Cards, involving six months of reporting, ten eyewitnesses, thousands of pages of public records, and a partnership with one of the leading experts on reinforced concrete structures in the US. The result was a multimedia representation of the investigation, which involved witness testimonials of the tragedy, construction experts, and consulting engineers, to dig into the causes of the construction’s weakness.

House of Cards, which won the coveted “Best in Show” category at the INMA Global Media Awards 2022, was published as an interactive narrative that used 2D and 3D animation, along with photos and videos from the collapse to illustrate what happened and explain why the tower fell.

ASSOCIATED PRESS Technology, including artificial intelligence, helps journalists who seek information about how something happened when they couldn’t be on the scene. The Associated Press constructed a 3D model of a theater in Mariupol bombed by the Russians and, combining it with video and interviews with survivors, produced an investigative report that concluded that 600 people died, twice the city government’s estimate of 300, in the deadliest single known attack against civilians in the Ukraine war.

AP journalists drew on accounts of 23 survivors, rescuers and people intimately familiar with the shelter operating at the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater, as well as two sets of floor plans of the theater, photos and video taken inside before, during and after that day and feedback from experts. The AP used the information to create a 3D model of the theater. Witnesses and survivors walked the journalists through the building virtually on the floor plan, pointing out where people were sheltering room by room and how densely crowded each space was.

After constructing the 3D model, the AP went back to witnesses to check and adjust. Two war crimes experts reviewed AP’s methodology of matching floor plans against witness descriptions, and concluded that it was as sound and definitive as possible in the absence of access to the site. AP also collaborated with the Human Rights Center at the University of California at Berkeley’s law school, incidentally the first college to offer an investigative reporting class that focuses specifically on open source visual techniques. In a 2021 investigation, AP looked at cases where bodies of those targeted indiscriminately by police and the military are being used as tools of terror. The findings are based on more than 2,000 tweets and online images,

in addition to interviews with family members, witness accounts, and local media reports AP and HRC Lab identified more than 130 instances where security forces appeared to be using corpses and the bodies of the wounded to create anxiety, uncertainty, and strike fear in the civilian population. Over twothirds of those cases analysed were confirmed or categorised as having moderate or high credibility, and often involved tracking down the original source of the content or interviewing observers.

HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE On 5 October 2020, Open Society Justice Initiative, Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, and Syrian Archive filed a criminal complaint in Germany on behalf of victims of the chemical weapons attacks on Eastern Ghouta on 21 August 2013. The complaint was filed under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

This historic step towards justice for the Syrian people was supported by student researchers at the aforementioned Human Rights Center, Berkeley School of Law, who used open source investigation methods to help build the evidentiary dossier.

The Investigations Lab’s Legal Investigation Team found corroborating open source information and evidence to support the criminal complaint and contribute to a dossier showing that the Syrian government used chemical weapons in violation of international law.

BBC In July 2018, a video showing women and children being blindfolded and gunned down by men in military uniforms started circulating on social media. Amnesty International raised accusations that the Cameroonian soldiers were responsible for killings occurring in the country.

In what experts continue to cite as an iconic piece of visual investigation though now fairly dated, BBC’s Africa Eye, its investigative unit on Africa, was able to identify when and where the killings occurred, the type of weapons used and the identity of the perpetrators. Digital forensics and open-source journalism were key to the piece.

The investigation proved that the military uniforms worn by the soldiers in the video were indeed those worn by some divisions of the Cameroonian military. Africa Eye also published a twitter thread that summarised the investigation report. It received more than 70,000 likes and 50,000 retweets.

The project pointed to the heavy reliance of open-source journalism on collaboration with non-journalists to contribute and verify facts. The team working on the project included three BBC reporters and a group of about 15 other collaborators that were organised in a Twitter group and a Slack channel. Analysts and researchers from Amnesty International also contributed to the investigation.

STORYFUL Leaders in the field cite the work of the website Storyful, which calls itself a social media intelligence agency. Storyful’s Investigations brings together, according to its website, “years of social news-gathering experience, elevated access to social media platforms, and the technology to parse millions of conversations.” Storyful analysed hours of user-generated video from the Capitol riot to piece together a timeline of how a mob of thousands overran police and attacked the U.S. Capitol. Protestors used social media to livestream the January 6, 2021 attack, which not only spread the unrest but provided news organisations with dramatic on-the-scene footage as the event unfolded in real-time.

Eyewitness videos identified and verified by Storyful show the evolution of events leading up, during, and after the attempted coup on Capitol Hill. From scenes of supporters of US President Donald Trump flying to Washington on January 5 and 6 to clashes with the police, Storyful reconstructed the major turning points.

THE RAINFOREST INVESTIGATIONS NETWORK (RIN) Funded by the Pulitzer Center, the network uses publicly available data to map forest loss and turn these into stories. It is developing new journalistic skills that mix statistical modelling, data, and cartography. In its first year, RIN has produced over a dozen in-depth investigations that have already had impact in the countries in which they were published. The stories are based on extensive research of public documents and have been produced with multidisciplinary teams of journalists, data scientists, and environmental science researchers. In its first year, RIN selected 13 journalists from 10 countries, who as Investigative Fellows dedicate themselves for a whole year to projects that mix fieldwork and building sources with data analysis.

In addition to the Fellows, the network has an editorial team of experienced investigative and environmental journalists, including an environmental investigations editor, a data editor and an editorial coordinator. With constant support from the Pulitzer Center’s senior editors and outreach teams, the editors closely follow the investigative projects and provide not only editorial advice, but also access to databases, analysis tools and other investigative resources. .

Example one:

This report by Jessica Brice published on the cover of Bloomberg’s Business Week magazine looks at the mechanisms of illegal land grabbing in the Brazilian Amazon. By consolidating public databases and scraping information from PDFs, the report shows the intricate legal gray zone that involves local politicians and the agribusiness presence in Brazil’s National Congress.

Example Two:

Published by Macaranga in partnership with the Southeast Asia Globe. Fellow Yao Hua Law analysed hundreds of environmental permit documents and found how a Malaysian logging company was infringing on the land of an Indigenous community. The reporter compared satellite images to illustrate the rapidly advancing deforestation at the site.

Because of these revelations, the community took legal steps to block the project and the permit was withdrawn.

THE Innovation in News Media World Report is published every year by INNOVATION Media Consulting in association with WAN-IFRA, The report is co-edited by INNOVATION President, Juan Señor, and Senior Consultant Jayant Sriram