13 Oct How to solve the ad-blocking crisis: Fix, don’t fight

Fighting ad blocking companies and consumers is like blaming the messenger; publishers should fix their user experience to stop abusing readers with ads that slow browsers, assault readers’ eyes and ears, secretly harvest personal data, and dump malware on their computers.

Who’s to blame for the ad blocking crisis? Look in the mirror.

Who can solve the crisis?

Look in the mirror again.

That’s right. We caused it.

And we can solve it.

But first, let’s take a step back to appreciate how we got ourselves into this predicament. It’s all about two sins.

It started with the publishing industry’s “original sin” — giving content away for free at the dawn of internet. A sin too many publishers continue to commit every day.

As a result, it is very difficult to get anyone to pay for content these days. Readers see free content as almost a birthright. The first sin then made the second sin inevitable. By giving content away for free, publishers left themselves only one option for covering their costs: advertising.

As print advertising revenues shrank, the pressure on digital ads to cover the revenue gap became intense. The obsession with automation and data collection in pursuit of short-range revenue gains drove publishers to pull out all the stops in giving advertisers every conceivable tool to grab readers’ eye- balls (and often their ears) and “steal” their personal data. It wasn’t long before animated, oversized, data-heavy, sound-enabled, auto-play, page-takeover, personal-data thieving ads made the user’s experience unbearable.

Today, publishers offer users desktop and mobile experiences that:

• Take forever to download because of the heavy load of features

• Secretly collect private data

• Inflate users’ mobile charges

• Drain device batteries

• Often introduce malware into users’ computers

• Assault users with loud automatic videos, and

• Abuse readers’ trust with personal tracking and targeted marketing that seems creepy, as if someone is constantly looking over their shoulder at everything they do.

Readers have reacted badly to being to mistreated and taken for granted. In a Digital Content Next (the former US-based Online Publishers Association) study, respondents said they dislike ads that:

• Cover content(70%)

• Automatically play with sound(70%)

• Track their online behaviour (68%)

• Cause webpages to load slowly(57%)

“In the last 12 years we have run after revenue targets, which have increased and increased, and therefore so have ad slots,” News UK’s head of audience and advertising systems Alessandro de Zanche told Digiday. “Ad tech was then brought in to increase the revenue and make quick money. The user has been mistreated and abused in the process, and now they are reacting.”

So now our readers are doing what anyone who is feeling abused would do: Remove the abuser from their lives.

And they are doing it in dramatically increasing numbers.

Stunning growth of ad blocking

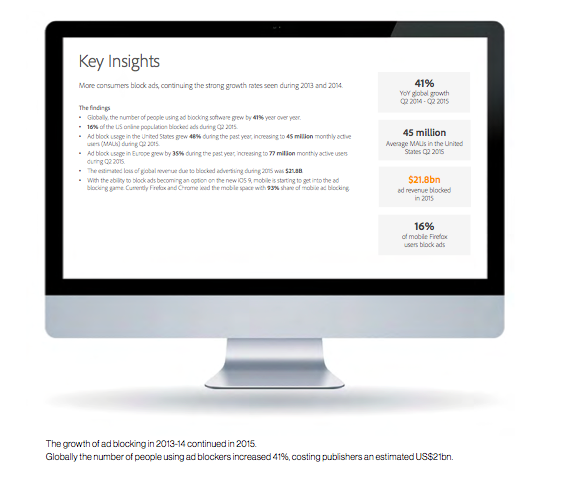

In the last six years, the number of global consumers installing ad blocking software has grown almost ten-fold to 198 million, according to the Page Fair/Adobe 2015 Ad Blocking Report. (Page Fair works with publishers to help them cope with ad blocking.) The pace is picking up: Ad blocking grew 41% globally from 2014-2015, including 48% in the US and a stunning 88% in the UK, according to the PageFair/Adobe report.

In some markets around the world, ad blocking is getting to the point of presenting a crisis for media companies whose business models is based on advertising. This is no small matter: At stake is $50bn in global online advertising revenue.

“Forty-seven percent of our US sample and 39% in the UK don’t always see ads because they use ad blocking software to screen them out,” the Reuters Institute of Journalism at Oxford University reported in its 2015 annual media business survey.

In other markets such as Greece and Poland, Page Fair found ad blocking rates approaching those of the US and UK: 37% and 35%, respectively. And yet, in Italy and France, ad blocking rates are only at 13% and 10%, respectively. Clearly, the ad blocking phenomenon is not yet global but no publisher serving ads as described above should relax.

Web browsers spark ad blocking surge

The reason ad blocking has accelerated in recent years is that the popular web brows- ers began providing free plug-ins to automatically nuke most ads, according to new media consultant Alan D. Mutter writing in his Newsosaur blog. “In the first six months of (2015), the number of users enabling the ad blocker on Google Chrome climbed 51% to 128 million, the number of ad blockers on Mozilla’s Firefox rose 17% to 48 million and the number of blockers on Apple Safari grew 71% to 9 million,” he wrote.

Ad blocking has exploded from a strictly geek thing to do, to become the fodder of radio talk show hosts and sitcoms. The US animated satirical cartoon series, South Park, introduced its reported 4 million viewers to ad blocking. US radio shock jock Howard Stern promoted Ad Block Plus on a show in October when he complained about internet advertising. Even NBC’s “Today Show” did a segment on ad blocking.

“Looking back now, our scraping of dimes may have cost us dollars in consumer loyalty,” wrote Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) senior vice president of technology and ad operations Scott Cunningham in October 2015.

Could the crisis be illusory?

And yet, there are still those who are whistling by the graveyard.

“The shadow [of ad blocking] appears very big but the reality is it is tiny,” Paul Lee, head of tech, media and telecoms research at Deloitte, told The Guardian.

Lee insists that 2016 will not be the US$41bn “ad-pocalypse” predicted by the likes of Page Fair.

Why? Google’s Android doesn’t have the “natural native support” for adblocking like that introduced by Apple, and Android runs on 80% of the 2.5bn tablets and smartphones out there, Lee said. “Then users have to actively download a blocker, which won’t work when they use apps, which is up to 90% of usage.”

“So relax, publishers: Ad blockers won’t destroy you tomorrow,” wrote re/code assistant editor Kurt Wagner at the end of 2015. “Still, it would be good to have a plan.”

“There is no sign of this supposed mobile ‘adblockalypse,’” City AM outgoing digital director Martin Ashplant told Digiday. Even the Interactive Advertising Bureau takes the official position that, having seen no slowdown in digital advertising in the UK with its 88% annual ad blocking growth, there must be no looming problem. Good luck with that, as they say.

But it won’t affect me

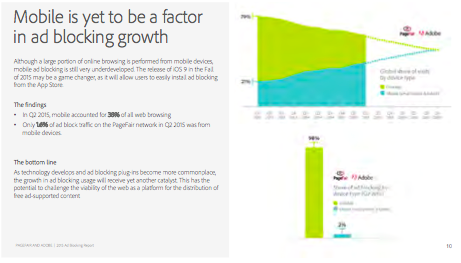

Some observers say not to worry because ad blocking affects gaming sites more than publishing sites, desktop much more than mobile, and mobile apps not at all.

That was true. Yesterday.

Don’t look now, but ad blocking is moving from individuals taking the initiative to block ads themselves to entire mobile networks offering millions of subscribers automatic or opt-in ad blocking. That’s huge.

Late in 2015 and again in early 2016, ad blocking company Shine announced partner- ships with network carriers in the Caribbean (Digicel) and Europe (Three Group) to offer millions of their subscribers automatic or opt- in ad blocking. The Shine system blocks most pre-roll video ads and about 95% of banner ads and popups.

Digicel last October 2015 gave its 13 million subscribers automatic ad blocking (users could opt out) and the Three Group in February 2016 unveiled its plan to offer subscribers in Italy and the UK and soon in Austria, Denmark and Sweden, 30 million in all, the opportunity to opt in to ad blocking. These initiatives are targeting average consumers, not gamers, and mobile users.

And, while male-oriented gaming and tech desktop sites had been more heavily hit by ad blocking, legacy publishers like Forbes, Axel Springer, Schibsted, Gruner + Jahr, Condé Nast, and many others are seeing increasing numbers of their visitors coming to their sites bearing ad blocking software.

“Irrelevant and excessive mobile ads annoy customers and affect their overall network experience,” Tom Malleschitz, chief marketing officer of Three in the UK, told AdAge. “We don’t believe customers should have to pay for data usage driven by mobile ads. The industry has to work together to give customers mobile ads they want and benefit from.”

Are in-app ads safe?

And lest those relying on advertising on apps get too comfortable with the lack of success of blockers in getting into their walled gardens, the very same tool that Shine is selling to Three and Digicel also blocks ads in apps.

The only places where in-app ads might be safe are in jurisdictions with tough regulations regarding so-called “net neutrality” like the US and the European Union. In those markets, telecommunications carriers are not allowed to block or degrade internet traffic for anything other than network security or purposes (like parental controls) provided for in individual nation’s legislation.

Back at the individual level, apps can kill ads in other apps, but to date those apps have not been allowed in app stores on Apple and Google. Both companies cited privacy concerns because those apps use privacy violating “deep packet inspection” of users’ internet behaviour, something browser ad blocking systems do not require.

In fall 2015, Apple removed the ad blocking Been Choice app, after initially approving it, and Google in 2013 removed AdBlock Plus, AdBlocker, AdAway and AdFree, and in February of 2016 Google removed Adblock Fast, Samsung’s newest Android blocker. Google’s rationale: The apps interfere with or disrupt the devices, networks, or services of third parties. Google Chrome users can still down- load the apps from the developers’ sites.

But where there is a driving will, there will be a way. Publishers hiding their ads in the walled gardens of apps should not feel comfortable.

The cost of this war over digital ads is getting serious. The amount of revenue publishers will lose will double to US$41.4bn globally in 2016, according to the same Page Fair/Adobe study. Another study by Page Fair for the International News Media Association estimated the revenue loss at mainstream news sites was 10% in 2015. And growing.

Who’s to blame?

Crises like these trigger the blame game. Surely, someone somewhere screwed up.

Is the ad industry itself to blame?

“If the rate of people who stopped eating corn tripled over a two-year period, would the head of the National Corn Growers Industry still have a job?” asked Ari Rosenberg, founder of ad sales consultancy Performance Pricing in a September 2015 MediaPost piece. “If 41% of millennials decided to stop drinking coffee, would the president of the National Coffee Association be under any pressure? If the National Football League experienced close to a 70% drop in attendance in just one year, would the commissioner of the league still be the commissioner?”

“So why, when consumers are blocking the serving of ads at these alarming rates, is the head of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) still employed?” he asked. “Here’s the truth: The online display advertising industry is a catastrophic failure because the IAB has condoned and promoted publishing behaviour that has led to this ad blocking epidemic.”

Of course, the IAB head, Randall Rothenberg, points his finger elsewhere: the brands.

Is it the publishers? Brands? Tech firms?

“To the degree that there is abuse of consumers, almost by definition it begins with the brands that are contracting agencies, which are in turn contracting publishers, which are then working with technology providers,” Rothenberg said at an IAB event in New York City in late 2015. “There’s a stream of activity that ends up in the consumer experience, and if that experience is bad, it begins with the brands.”

Or are the publishers at fault?

“Publishers’ thirst for ad revenue has driven them to work with more ad tech partners, in turn creating a bad reader experience,” said Digiday media writer Ricardo Bilton in a 2015 retrospective piece. “Publishers, under this line of thought, only have themselves to blame.”

Publishers aren’t taking that line of thinking lying down.

Publishers may get dinged for running intrusive, resource-intensive ads, but the pres- sure to do so comes from the people holding the money, Joey Trotz, vice president of advertising at Turner Broadcasting, told attendees at that IAB event in the fall of 2015.

The brands’ desire for bigger, more elaborate, more targeted ads — an increasing percentage of which are video drives ads that create a significant drag on page performance, data use and battery life — has driven more people to install ad blockers, Trotz said.

But there is plenty of blame to go around.

“Publishers are to blame. So are brands. So is ad tech,” wrote Bilton at the end of 2015. “There’s been no shortage of finger-pointing when it comes to ad blocking. The easy culprit is ad tech, which has taken the bulk of the blame, thanks to its facilitation of intrusive auto-play video ads, behaviour tracking, and slow load times. Agencies have pointed the finger at publishers, which may have brought the ad blocking menace on themselves. And then there’s the likes of the IAB, which says the brands and agencies are as much to blame as any other group.”

Focusing on the symptom, not the illness

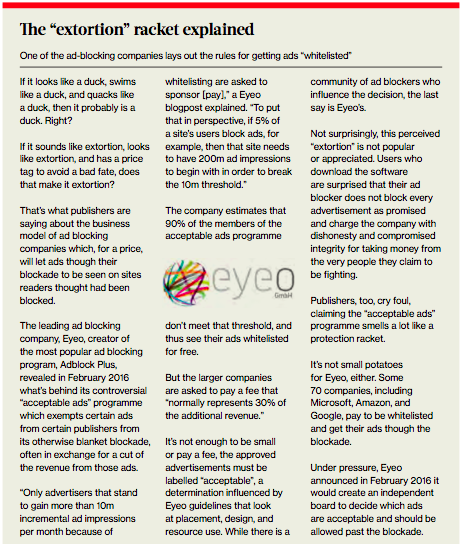

Some media and ad industry execs like to deflect blame and attention, turning their wrath on the ad blocking software providers themselves. IAB’s Rothenberg calls them an “unethical, immoral, mendacious coven of techie wannabes”.

In his IAB speech in the fall of 2015, Rothen- berg described the maker of the most popular blocking software, Adblock Plus, “an old-fashioned extortion racket, gussied up in the flowery but false language of contemporary consumerism.” Early in 2016, New York Times CEO Mark Thompson told Social Media Week attendees that ad blockers and the people who use them were no better than people who steal news- papers from a newsstand.

“Trying to use and get benefit of the Times’ journalism without making any contribution to how it’s paid is not good,” he said. “In the end, they’re not really helping pay for what they consume. Everything we do should be worth paying for. Everything should feel like it’s HBO rather than a broadcast network.”

And the ad blocking companies’ practice of offering to “whitelist” certain ads for publishers and let them slip through the ad blockade, often for a substantial payment, is nothing more than extortion, according to both Thompson and Rothenberg.

They “are asking for extortion to allow for ads to take place,” Thompson said at Social Media Week. “That should not be allowed.”

Ad blocking is robbery, plain and simple – an extortionist scheme that exploits consumer disaffection and risks distorting the economics of democratic capitalism, wrote Rothenberg in AdAge in September 2015. (See the IAB’s “The IAB’s four-point plan to solve the ad blocking crisis” sidebar.)

The ad blockers themselves, however, feel no less passionately.

“We are as motivated to protect consumers as advertisers are to abuse them,” Roi Carthy, the chief marketing officer for Shine, told The New York Times. “This is a holy war for us.”

In the end, blame is a fool’s game. And a waste of valuable time.

First serve the real customer — the audience

It is time to move on and make ad blocking a moot point, a business without a consumer need.

“We built all these sites and places for ads to live but rather than give real thought to the landscaping, we just let everything grow. Now, everyone is saying, ‘we’ve got kind of a mess here so we need to take a step back and clean things up,’” Quartz publisher Jay Lauf told Digiday.

“You have to first serve your real customer, your audience, so you can have the foundation for a solid business,” he said. “No one has the luxury any more of ignoring the user experience.”

“The companies that are going to be successful down the line understand that content is a big differentiator but the entire experience is a part of that content as well,” Digital Content Next CEO Jason Kint told Digiday. “It’s all about the entire package of speed and performance and technology. The consumer doesn’t differentiate between publishers based on content alone.”

“Recent IAB research shows that if presented with a straight choice between either paying for content, or viewing advertising, a comfortable majority of consumers say they’d prefer to continue seeing ads online,” wrote Lolly Mason, head of media partnerships at cross-screen creative technology platform, Celtra, on BrandKnewMag.com. “By focusing on improving user experience, and delivering ads that are truly engaging, advertisers and publishers will halt the uptake of ad blocking technology and can begin to repair relation- ships with their consumers.” It’s a short- and long-term strategy. “These actions are likely to result in fewer, more creative ads per page and over the longer term, will lead to an increase in average CPM rates,” Mason wrote.

Given what’s at stake, that strategy is easier said than done.

Fight or fix

At present, publishers are more focused on fighting ad blocking rather than on fixing the core reasons behind it.

Instead of doubling down on improving the user experience, in particular the advertisements, publishers are playing with strategies to get readers to turn off their ad blockers, or even suing the ad blockers in court.

While that is not quite fiddling while Rome burns, those publishers are leaving the sickness untreated while treating symptoms. If publishers could just begin to make the user experience rewarding and pleasurable again, they’d kill the need and demand for ad blocking, and, thus, kill the business model for ad blocking companies.

Ad blocking “makes sense to me” from the perspective of consumers, Gawker Media head of programmatic Eyal Ebel told the Digiday Programmatic Summit in the fall of 2015. “In- stead of trying to figure out how to get around ad blockers, you should figure out why people are blocking ads.” And fix it.

“As an industry, we have lost some trust and must accept that and address it,” managing director of Dennis Digital Pete Wootton told the Digiday Summit. “Some are trying to make out it’s a moral argument. It’s not; it’s a commercial argument. It’s a wake-up call to do things differently.”

Getting distracted from the real job

But instead of doing things differently, some publishers are trying to figure out how to create ads such as native ads or in some cases pre-roll video ads that can’t be sniffed out by the ad blocking software. Others are putting their faith in advertising within the walled garden of apps.

Still others are trying to figure out a system to get readers to “whitelist” their site in their ad blocker app to allow that publisher’s ads through the blockade. Others ask readers to turn off their blockers simply because advertisements support the good work they do (a guilt-trip approach that is very modestly successful). Others offer an “ad-lite” experience if readers turn off their ad blocker.

Some publishers are offering readers the opportunity to pay for the privilege of an ad-free experience. And some ask readers to subscribe to access content.

In a bit of irony, some publishers’ appeals to their readers are also blocked if the ad blocking software detects an abusive approach such as an obtrusive appeal that takes over a page or pops-up in the middle of content.

One ad-tech company, BlockIQ, is offering publishers the chance to defeat ad blocking software and serve ads to all of their readers, even the ones with ad blocking software. BlockBypass will either keep the publisher’s content behind a wall, releasing it only when the reader turns off the ad blocking software, or circumvent the ad blocking software altogether and serve the readers ads anyway.

“We built all these sites and places for ads to live but rather than give real thought to the landscaping, we just let everything grow. Now, everyone is saying, ‘we’ve got kind of a mess here so we need to take a step back and clean things up,”

Jay Lauf

Publisher, Quartz

Here is a sampling of publishing companies’ methods of dealing with the ad blocking crisis:

AXEL SPRINGER

Last October, the German publisher’s Bild tabloid was seeing 25% of its 10 million uniques visitors blocking ads, according to comScore. Germany is one of those countries with a high (and increasing) number of consumers using ad blocking software (25% according to Page- Fair).

The publisher then asked its readers to either turn off the ad blockers, whitelist the site, pay US$3.23 a month, or lose access. The response was impressive: Two-thirds of the readers turned off their ad blockers, creating three million new “marketable visits” the company could monetise.

BILD is simultaneously pursuing legal action against the ad blockers. The company has lost two cases in court but insists they are making headway with every effort. “Since we’ve established this model, the courts are beginning to lean toward our argument,” BILD.de editor in chief Julian Reichelt told Digiday. “Now the courts and judges have more of an understanding. We will start to win these cases.”

WIRED

With 20% of their readers using ad blocking software, Wired started giving readers three options: 1) Whitelist Wired in their ad blocking software; 2) Pay US$1 per week to access an ad-free site, or 3) Go away. Wired is hoping a significant portion of their readers who use ad blockers will respond positively to the company’s appeal and whitelist Wired to enable the ad model to support the content they want to read for free.

FORBES

Forbes was seeing 13% of its readers using ad blocking technology. “13% adds up to a good- size city of people who aren’t seeing ads on our site — and that adds up to real money,” wrote Forbes chief product officer Lewis DVorkin.

“So, that led us to ask ourselves, what if we cut back the number of ads to consumers who turned off the ad blocking software when visiting forbes.com?” DVorkin wrote. “And that’s exactly what we did. Since 17 December 2015, a small percentage of those with ad blockers received this message:

“Thanks for coming to Forbes. Please turn off your ad blocker in order to continue. To thank you for doing so, we’re happy to present you with an ad-light experience.”

From 17 December to 3 January 2.1 million visitors using ad blockers received the ad- light experience offer. Incredibly, almost half of those readers (42.4%) did turn off their adblockers, and they received a thank-you message in addition to access to the ad-light site.

However, that “ad-light” experience is hard- ly ad-free. Each page still has a 730×90 leader- board, three 300×600 pixels display ads, and eight “From the web” paid content placements. Importantly, the pages do NOT include autoplay video or animation.

“We monetised 15 million ad impressions that would otherwise have been blocked,” wrote DVorkin.

VERDENS GANG

Schibsted’s Norwegian media group, Verdens Gang (VG), has taken the slow-cook approach. They decided to research why their readers might be using ad blocking software. When a reader using an ad blocker got to the site, they were greeted with a survey asking why they were using an ad blocker. This gave VG the opportunity to convert ad blockers with a message making the argument that advertising revenue supported their journalism and offering instructions on how to whitelist the VG site.

As a result, ad blocking dropped 20% to 14% of VG visitors, or 25,000 monthly uniques.

Those 25,000 readers received another survey to determine what motivated the typical VG ad blocker. The results revealed that the blockers were predominantly young males ages 18-29, a good percentage of VG’s future audience. The survey also sought to identify ad blocker user objections and ways to improve the user experience sufficiently to entice them back.

A significant percentage of those users told VG they would whitelist VG if:

- Flash ads were removed (19% would consider whitelisting)

- Relevant ads targeting consumers were displayed (24% would consider whitelisting)

- Pop-up ads were removed (28%would consider whitelisting)

- Blinking, moving ads were eliminated (47% would consider whitelisting)

- Fewer ads were displayed on the site (47% would consider whitelisting)

- If the site had a quicker load time (48% would consider whitelisting)As a result, VG moved aggressively to reducesite load time and begin discussions with media agencies and their advertisers to improve ad quality, jointly creating new rules that went into place this January 2016 calling for useful, non-tracking, static ads.VG also opened discussions with their Norwegian competitors looking for industry-wide solutions implemented by all publishers in the country.

GRUNER + JAHR

Before banning access to readers with ad blockers, Gruner + Jahr’s special interest title Geo was giving ad-free access to the 22% of its readers who employed ad blocking software, Oliver von Wersch, G+J Digital’s managing director of growth projects, told Digiday. Then the magazine decided to shut the doors, telling its visitors, turn off your ad blocker, pay per day (US$.50) or week (US$2.22), or lose access. Three months later, the number of visitors with ad blockers had dropped 35% with no drop in overall traffic, von Wersch said.

G+J tried the same strategy with three other titles (a food and recipe site and two interior design titles), and got results even faster: one week! The food title saw ad blocking drop by 30% and the other two sites experienced similar success.

SLATE

Slate is reported to be losing eight percent of its revenue to ad impressions lost to ad blockers. But it is actually doing something about the user experience that drives readers to employ ad blocking tools. They are eliminating intrusive ads on their site while also asking visitors with ad blockers to sign up for premium membership.

Soon they will ask readers to turn off their ad blocker, but only after having already improved the user experience.

SPANISHDICT

The world’s largest Spanish-English dictionary, translation, and language learning website is taking a unique approach: No bans, no appeals, no lawsuits, just outreach and repair.

Because the site relies on programmatically-placed ads, it has no control over the quality of the ads appearing on its site. With an estimated 12 % of its visitors using ad blockers, the managers of the site decided it was time to act.

In an effort to remove offensive ads and block offending advertisers, the site created a tool asking visitors to report bad ads.

It’s working. Some ads drive as many as 400 complaints, usually autoplay videos, and the company has taken action on about one-third of the offending ads.

SpanishDict is cleaning up its user experience to keep readers from resorting to ad blockers. “We can’t affect the format when we serve ads programmatically [and] I’m not by any means pro ad blocking. But we ought to be asking, what as publishers can we do to change the experience on our site?” Jordan Woods, SpanishDict ad operations manager, told Digiday.

There’s no time to waste

Given limited time and resources, publishers should focus on fixing the user experience, respecting their most valuable asset (their readers), and removing their motivation to engage in ad blocking.

Readers still want free content, and have said they’d accept advertising as the “price” for free content, but not abusive, intrusive ads that violate personal privacy.

Fix the system. Remove the need for ad blockers. Kill the ad blocking companies.

Now.

This article is one of many chapters published in our Innovation in Magazine Media 2016-2017 World Report.