11 Feb Choose Your Media Technology Wisely: Innovations to Strengthen Your Media Brand in 2019

Over the last year media technology has continued to do what it does best: surprise us. We’ve seen innovation in augmented reality and virtual reality change the way we think about and produce news. We’ve seen the growing interest in and the strengthening of AI, blockchain and chatbots.

It is essential for publishers to invest in the right technology and not be distracted by the latest shiny thing. According to a special report on technology adoption strategies published by Publishing Executive, NAPCO Research and Fuse Media.

“The wrong technology can eat up valuable time, resources, and mental bandwidth,” the authors wrote. “Or worse, operating in an environment of thin margins, the wrong tech investments today can have strategy and financial implications that ripple for years.”

So, it’s wise to investigate the latest tech, and invest in the areas that make sense for media. The more news media learn about tech, the more

they can experiment with it, try it out or use it. Because, if newspapers don’t investigate or participate, they are at risk of being left behind. According to Amy Webb, CEO of the Future Today Institute for Nieman Reports, news publishers should participate in this area, “rather than become consumed by it,” she said.

Here we take a look at some of the key tech developments that publishers should be watching:

-

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND AUTOMATION

-

BLOCKCHAIN

-

CHATBOTS

-

PROGRESSIVE WEB APPS

-

VOICE

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND AUTOMATION

Artificial intelligence, or AI, refers the development of algorithms with ‘intelligence’: they are able to perform complex tasks, with the most ‘intelligent’ able to learn from experience and improve their offering over time. According to Fast Company editor Robert Safian, AI is poised to “affect not only the businesses but also the everyday lives of people around the world.”

According to the Reuters Institute Digital Leaders survey of news publishers, 35 per cent of the news industry is already using some kind of artificial intelligence. AI has been used in news companies across departments, from advertising, sales and marketing, to reader acquisition, and editorial.

AI is being used as a distribution tool, allowing algorithms to select stories for users. For example, with funding from a Google grant, The Times and The Sunday Times are developing a recommendation tool internally known as James, “an AI digital butler,” that learns reader preferences and habits, delivering content in their preferred format and at their preferred time, according to Press Gazette.

AI can “help reporters find and tell stories that were previously out of reach or impractical,” suggested a report published in September 2017 by the Tow Center and the Brown Institute for Media Innovation. The Washington Post saw potential for an AI system that could generate explanatory, insightful articles. Heliograf debuted last year, to generate stories with the help of editor-created story templates. UK news agency Press Association (PA), partnered with Urbs Media to create 30,000 localized news reports every month, according to a recent story in Forbes. The project is known as RADAR (Reporters and Data and Robots).

The Associated Press began using algorithms to produce thousands of automated earnings reports in 2014, “and estimates that doing so has freed up 20 per cent of journalists’ time,” according to an AP Insights report by Francesco Marconi, formerly strategy manager and AI co-lead at The Associated Press (now R&D Chief at The Wall Street Journal). “Greater speed, accuracy, scale and diversity of coverage are just some of the results media organizations are already seeing,” he wrote.

This point is especially valid given the large amount of information and data that journalists are presented with on a daily basis. “(AI) can enable journalists to analyse data; identify patterns, trends and actionable insights from multiple sources; see things that the naked eye can’t see; turn data and spoken words into text; text into audio and video; understand sentiment; analyse scenes for objects, faces, text or colors – and more,” Marconi wrote.

In March 2018, Reuters announced it was developing an in-house tool called Lynx Insight, to aid its journalists “by identifying trends, anomalies, key facts and suggesting new stories reporters should write,” wrote Chief Operating Officer Reginald Chua on the Reuters website. “Through Lynx Insights, we’re placing a bet that the future of automation in the newsroom is less around using machines to write stories than in using machines to mine data, find insights, and present them to journalists.”

BLOCKCHAIN

Blockchain is a decentralized, digital ledger in which transactions made in crypto-currency are recorded. It offers a way to verify transactions without the need of a central authority, like a bank. It is immutable and nearly impossibly to corrupt. It is global technology that millions of computers (nodes) have access to, and thus, is public by default.

“Blockchain technology can create both chains of authenticity and a level of security,” Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism told Nicky Woolf, a writer for The Guardian on Medium. “Journalism in a highly distributed world, particularly where it is increasingly relying on third-party technology, is in need of solutions to those two problems.”

Blockchain’s use for the news media industry could be two or three-fold:

- Impact on distribution of content, connecting users and producers in a decentralized and secure way.

- Monetising content and creation of new revenue streams.

- No deletion of archives or third-party censorship as blockchain is near impossible to tamper with.

In terms of creating revenue streams for journalistic institutions, Blockchain could offer a micropayment solution to solve the industry’s current economic hurdles. For example, at Civil’s core is the idea of peer-to-peer transactions. Civil, a blockchain-based journalism marketplace, which recently secured $5 million in funding from Ethereum studio ConcenSys, aims to use blockchain “to build decentralized marketplaces for readers and journalists to work together to fund coverage of topics that interest them,” according to Niemanlab’s Ricardo Bilton.

Speaking at the Digital Innovator’s Summit in March, Civil’s co-founder Daniel Sieberg outlined that his startup is aiming to create a direct relationship between newsrooms and audiences. “We think that there are aspects of blockchain that can really help to change the equation between journalists and audience, opening up trust and transparency in a way that we haven’t seen before,” he said.

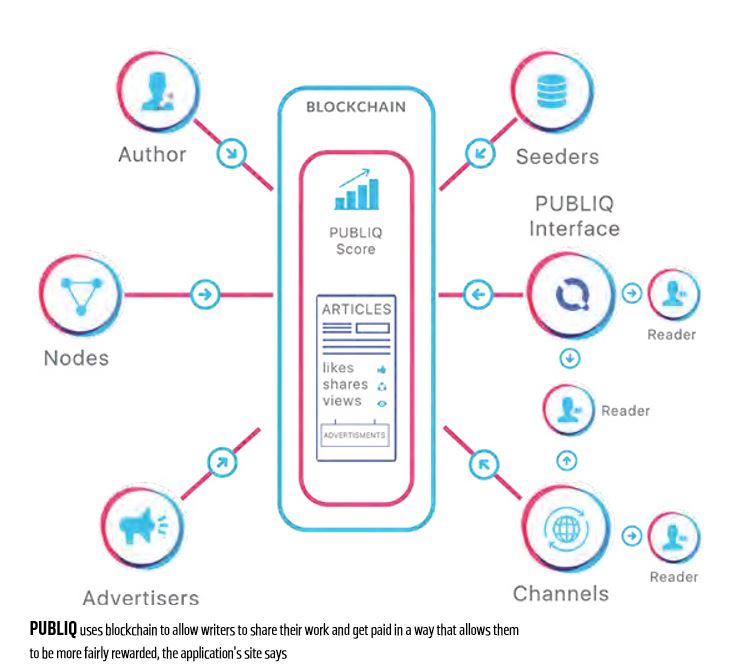

In 2017, Swiss-based blockchain content distribution platform DECENT launched PUBLIQ, a third-party application that allows writers to share their work and get paid. Writers build their reputation based on feedback from readers who purchase content and get paid based on their PUBLIQ reputation score. “This unique evaluation system will allow authors to be more fairly rewarded, as well as praised or celebrated for their good work,” according to the site.

Blockchain-based entities could also provide space spaces for journalists to fight censorship and retain archives. As blockchain is public, no government or third-party could alter a block without notice. At a time when archives of news sites can disappear on a billionaire’s whim (see Gawker, DNAinfo, Gothamist), archives of digital material could be stored in the blockchain itself.

However, blockchain is still a very new technology. One of the biggest challenges of using blockchain for journalistic purposes and endeavours is its lack of adoption. “Blockchain relies on a network of participating computers and nodes, and if no one participates, it won’t work,” notes Guardian writer Nicky Woolf on Medium. We believe it is a technology to watch beyond 2019.

CHATBOTS

Conversation is now a key digital interface. Chatbots allow users to ask for news, weather, or to purchase flowers. “Margot” the Lidl chatbot dishes out wine tips, while “Hazel” the HGTV chatbot inspires its users with trending design ideas. They can pay parking tickets or send dinner ideas, and there’s even a chatbot that will talk to your friends for you: called Reply, the bot will take the hassle out of socializing by reading your social media messages and suggesting automatic replies based on your normal chatting habits, according to TechRadar.

According to eMarketer, one quarter of the world’s population is expected to use messenger apps like WeChat, WhatsApp, Messenger, Kik, Telegram and Line by 2019. “Over 2.5 billion people have at least one messaging app installed, with Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp, leading the pack,” according to a recent article in The Economist.

By 2020, a customer will be able to solve 85 per cent of his or her problems with a business without ever talking to a human being on the other side, according to Gartner Research predictions. Media companies all over the world, including The Washington Post, The Guardian and The Texas Tribune, have experimented with chatbots over the last year.

In Australia, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation launched a Facebook Messenger bot in 2016, created in partnership with Chatfuel. The bot sent users daily headlines and alerts. In the first month of operation, the news chatbot had more than 70,000 subscribers, Deputy Editor (Mobile) Lincoln Archer told Backstory. “The best feedback we’ve had is from people who’ve found us not just cool or clever but useful,” he said. “We’ve saved them time, got them up to speed fast, or given them something to talk about.

Chatbots also featured prominently in elections in 2017. Last March, The Texas Tribune developed a chatbot for Facebook Messenger in partnership with Andrew Haeg at GroundSource. The bot, called Paige, delivered news to users about the Texas legislative session and was intended to reach new audiences. “Paige’s goal is to make Texas politics easier to follow, but she’s not just another mobile notification service,” wrote chief audience officer Amanda Zamora in an article introducing the new feature. The bot was intended to reach new audiences and get feedback from its existing audience.

Chatbots hope to engage audiences in conversation and nudge them along to subscription or purchase. “Like more early stage tech, chatbots are a solution in search of a problem,” wrote Andrew Haeg, on the Reynolds Journalism Institute blog. “Over time, bots might help newsrooms super-engage with a smaller, more devoted audience instead of engaging a large audience in a series of one-off dopamine hits.”

But, before all news publishers join the chatbot bandwagon, there are some questions they ought to ask themselves: what services will the bot provide? How will the bot fit the personality and tone of their news brand? How will the chatbot be monetized?

PROGRESSIVE WEB APPS

The native app boom is over and the progressive web app (PWA) is on the rise. Web apps look likely to become the new way of interacting with audiences, because they’re fast, responsive, and far less expensive than creating an app.

Progressive web apps don’t have to be downloaded, are easy to use, safe, and work on any device. They act and feel like native mobile apps, offering immersive, fullscreen experiences. Yet, PWAs are websites that can also work offline – because they’re built using service workers – bits of Javascript that run in the background of a browser that act as proxy servers, caching data and content and providing access when users have low or no connectivity. The Financial Times, for example, has a PWA at app.ft.com, which can be saved on a user’s device home screen and allows for offline reading.

As far as mobile experiences go, progressive web apps offer a smoother and more robust experience than mobile browsers, and offer additional features like push notifications. And, as users access more and more content on their mobile devices, speed is seen as not only a differentiator in the market, but also essential for good user experience. Wired, for example, launched a PWA in October 2017 to boost page speed, according to Condé Nast.

The Washington Post’s PWA is found at washingtonpost.com/pwa, functions like a native mobile app and loads mobile pages in under a second. “Readers want instant load times, and the combination of Google’s AMP and Progressive Web App technologies allows us to offer a gamechanging experience for the mobile web,” wrote Shailesh Prakash, Chief Product and Technology Officer for The Post.

VOICE

When was the last time you began a command or a question with the words, “OK, Google,” “Hey, Siri,” or “Alexa?”

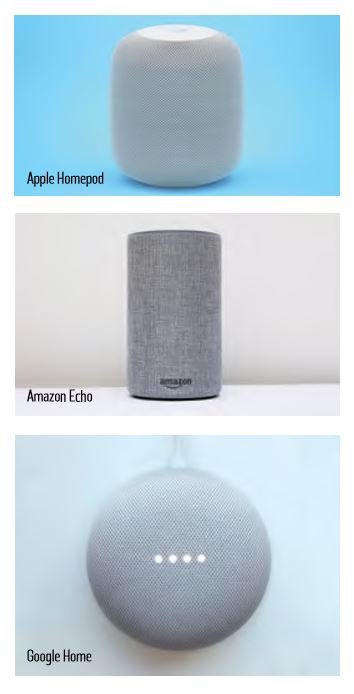

Adoption of voice devices has been steadily increasing. Amazon sold more than 20 million voice-enabled devices in 2017, and according to Google’s Keyword blog, the company sold more than 6.8 million Home speakers over the 2017 holiday season alone. And, voice-enabled devices aren’t limited to the West, as there multiple voice-activated personal assistants produced by Chinese companies Tencent, Baidu and Alibaba.

According to eMarketer, voice searches will make up 50 per cent of all searches globally by 2020. Voice-activated personal assistants include Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft’s Cortana, Google’s Home and Assistant, and Apple’s HomePod. People can get recipes, stock quotes, pizza, podcasts, or listen to news on voice platforms.

Demand for voice devices is expected to generate $3.5 billion by 2021, and brands that leverage voice platforms “will see rapid growth in digital commerce revenue,” according to Gartner’s top 2018 predictions.

“The Smart Audio Report,” recently published by National Public Radio and Edison Research, found that top activities for voice-enabled smart speakers included listening to and playing music, asking questions, getting the weather, listening to radio or getting the news.

For news publishers, voice platforms introduce yet another distribution channel to produce specifically-designed content for.

“Don’t think of voice as a platform – think of it as just the latest content command and control system. From keyboard, to mouse, to touch screen, to voice interface — just one more way for your audience to activate your content,” wrote media veteran Peter Houston for Publishing Executive.

For early adopters, the idea behind jumping on the voice bandwagon was about brand recognition, building habits with users and building new audiences. After all, speaking is intuitive and voice platforms are beginning to change behaviors and form habits.

For early adopters, the idea behind jumping on the voice bandwagon was about brand recognition, building habits with users and building new audiences. After all, speaking is intuitive and voice platforms are beginning to change behaviors and form habits.

Most major media companies have experimented with voice platforms, expanding the list of places and spaces to connect with their audiences. News publishers can develop skills – the name given to a function or app for Alexa – or actions – the name given to a function or app for Google Assistant.

Companies that have developed skills for Alexa include NPR, The Washington Post, and Harvard Business Review. Users can ask Alexa for a Wall Street Journal ‘Flash Briefing’ summary, catch up with The Economist’s Espresso, or get micro-news updates from BBC News, NPR, CNN, Tech Crunch, ABC News, CNBC, from Canada’s The Globe and Mail, or The New York Times, among others.

The Guardian launched a skill for Alexa in 2016, allowing users to ask The Guardian for headlines, the latest football scores, or film, book, music and restaurant reviews. “And you can also listen to our popular weekly podcasts. We cover a wide range of interests – Politics Weekly, Science Weekly, Football Weekly or Close Encounters,” wrote Chris Wilk, group product manager at The Guardian.

NEW TECH ON THE HORIZON

Other tech advances that might be of interest to news publishers include the growing array of smart devices, from wearable items to appliances such as refrigerators. The potential for news providers, however, is not yet clear.

For now, focusing on the conversational slant of chatbots and voice, the efficiencies offered by AI and on providing the best experience across platforms with a progressive web app is a good place to start.

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovation in News Media 2018 World Report.