06 Nov Progressive versus native apps: When was the last time you found a no-brainer solution to a media problem?

Here’s one you can take to the bank: progressive web apps.

Still think you need a native app?

Think again.

Still believe those stats about how we spend 500 per cent of our time in apps, not the mobile web?

Misleading.

Got US$100,000 lying around to build a native app for iOS and Android that almost no one will download and 90 per cent of those who do will delete after three months?

Doubt it.

Want to continue publishing expensive content in a walled garden for a relatively small audience where it can’t be shared or discovered by anyone except your subscribers?

Then, by all means, keep feeding your native app.

Remember Wired magazine’s September 2010 headline: “The Web Is Dead”?

They were wrong.

The arrival of what are called “Progressive Web Apps” (PWA) is beginning not only to level the playing field between native apps and web-based PWAs, but also to begin tilting the field in favour of the PWAs.

Let’s start, however, by acknowledging the initial power of native apps.

First of all, there are a billion of them.

Well, not quite: There are almost five million apps in the Apple App Store and the Google Play app store combined, according to data firm mobile app analytics platform AppFigures. By 2020, there will be five million apps in the App Store alone, according to app intelligence firm Sensor Tower.

And more apps are being created and sold every day.

Apple’s App Store recorded its biggest revenue month ever in December 2016, according to Phil Schiller, the company’s senior vice president of worldwide marketing.

The App Store made US$3 billion in revenue in December alone, from a combination of in-app purchases, paid downloads, and fees for subscriptions, Schiller told The Verge. In all of 2016,Apple made around US$8.57 billion in App Store revenue, he said. Most of the App Store revenue still comes from games, according to Schiller.

“Ever since the first iPhone came to market, having an application in an app store has been considered the Holy Grail of the entire publishing industry, whether we’re talking about news- papers or magazines,” Ciprian Borodescu, CEO at Appticles, a multi-channel mobile publishing platform, wrote on his company’s blog. “Most publishers, to this day, have religiously followed the path to app store publishing. Publish it and they will come!”

Well, yes and no.

If you have a hot, big-name game app or if you’re Facebook, yes, they’ll still come. But few magazine media companies are in that stratosphere. For most magazine media companies, the app boom, if it ever happened, is over.

“The app store’s middle class is small and shrinking,” wrote Casey Newton, Silicon Valley editor of the tech site, The Verge. “The easy money is gone. For all but a few developers, the app store itself now resembles a lottery: for every breakout hit like Candy Crush, hundreds or even thousands of apps languish in obscurity.

“Apps for massive social networks, on-demand services like Uber, and subscription businesses like Netflix and Spotify remain in high demand,” wrote Newton. “Then there’s gaming: Last year, 85 per cent of all app revenues went to games, according to App Annie.

“Meanwhile, a fatigue is setting in among customers… by 2014, the majority of Americans were downloading zero apps per month, accord- ing to ComScore,” wrote Newton. “And it turns out people simply don’t use most of the apps they do download. According to ComScore again, the average person spends 80 per cent of their time on mobile devices using only three to five apps.”

Nonetheless, the allure of being in the two big app stores still entices some media companies. “It’s easy to see how a lot of publishers end up with tens of thousands of dollars invested, months spent in developing and promoting the application, for a staggering 1 per cent converted into mobile app users from their already existing web traffic,” wrote Borodescu.

“I would argue that being in an app store has no major advantage because it has been shown that if you are not in the top 0.1 per cent of apps in the app store, you are not getting significant benefit from being there,” Ada Rose Edwards, developer advocate for Samsung, explained to Borodescu.

For media companies, there is a laundry list of reasons not to develop native apps:

- 94 per cent of app revenue comes from 1 per cent of publishers, according to measurement site SensorTower

- The average app loses 77 per cent of its Daily Active Users (DAUs) within the first 3 days after the install, according to mobile intelligence company Quettra, Within 30 days, it’s lost 90 per cent of DAUs. Within 90 days, it’s over 95 per cent. In other words, the average app loses almost its entire user base within a few months, according to Quettra

- Of the millions of apps in the Google Play store, only a few thousand sustain meaningful traffic, according to Quettra

- In-app purchases are where the money is — only 5.2 per cent of users spend money on in-app purchases, and the commerce is regulated by the platform, or the platforms take a percentage, according to global mobile marketing analytics company AppsFlyer

- 60 per cent of apps in the Google Play app store have never been downloaded, according to Google AdWords

- The average user downloads less than 3 apps per month; half of US smartphone users download zero apps per month, according to ComScore

- Native app install friction blocks 74 per cent of your potential customers before they can use your app, according to Chris Heilmann, Microsoft program manager for developer outreach, speaking at the Devternity development conference in Riga, Latvia in December 2016.

By some accounts, 20 per cent of users drop out of the app installation process for every click required to get an app installed and running, Heilmann said. For example, if 1,000 users are interested in your app, only 800 will take the initiative to visit the app store, only 640 will successfully find your app, only 512 will click to install, only 410 will accept permissions, only 328 will wait for it to download, and only 262 will actually use it, said Heilmann.

Native app critics argue that statistics like those indicate we have reached what Walt Mossberg, executive editor at tech site The Verge, calls “peak app”.

“I think the novelty of the app itself has worn off — we’ve reached peak app,” wrote Mossberg on TechRepublic. “Just as there are too many confusing, often redundant choices on the breakfast cereal shelves at the grocery store, there are too many duplicative and puzzling choices in the Apple and Google Play app stores.

“Given the plethora of (often bad) choices, we, as consumers, have given up on apps. I am not against apps as a software type. Just the opposite: I believe them to be crucial to mobile devices… And it’s still possible to create a sensation with a great app that introduces genuinely new experiences — like Pokémon Go,” wrote Mossberg. “But one reason Pokémon is so news- worthy is that such blockbuster apps are rarer and rarer. Unless an app becomes one of the three to five apps you use every day, “it could remain on your phone, gradually migrating to a place where it’s rarely seen or is always swiped past, until it’s finally deleted,” wrote Mossberg.

Native app defenders, however, point to all those statistics about how much more time is spent on apps versus the mobile web.

“Everyone likes to cite the factoid that mobile users spend 86 per cent of their time in apps, not the web,” wrote Adobe vice president of mobile Matt Asay on TechRepublic. “It’s a true statement. It’s also irrelevant.”

“Because, let’s face it: they’re not spending time in your app. For any given individual, nearly 70 per cent of the time they spend in apps is con- fined to their three most frequently used apps, according to Flurry data,” Asay wrote. “The odds of anyone using your app are pretty slim.”

“People look at the data around the amount of time people spend in apps versus the web and mistakenly think that means people aren’t visiting mobile websites, or aren’t doing things on mobile web,” Jason Grigsby, co-founder of website builder Cloud 4, told Fast Company.

“I hate that statistic… it’s just an asinine measure.”

“There is a large audience of people accessing the mobile web that you shouldn’t ignore — Comscore found that mobile web audiences are almost three times the size and growing twice as fast as app audiences,” said Grigsby.

Across the top 50 mobile web properties, only 12 have more traffic coming from apps than the browser, according to research by Morgan Stanley and ComScore.

And except for the highest-profile apps, consumers are increasingly resistant to downloading native software onto their devices, Max Lynch, co-founder and CEO of mobile app-builder Ionic, told FastCompany.

Even if you’ve gone to the expense of building a native app (at US$50,000-$100,000 for a single app in both iOS and Android), “keep in mind that building an app is the easy part,” wrote Asay. “Next, you have to acquire users — according to Fiksu, that will run you US$1.46 (iOS) to US$1.15 (Android) per app download. I’ve heard of some companies paying upwards of US$70 per app download.

“All of which sounds less appealing when you consider that roughly 52 per cent of apps lose half of their peak users after just three months,” again according to Flurry data, he wrote.

And then you have to spend money to retain them. “The cost of retaining users, ironically, is even more expensive than acquiring them in the first place, according to Fiksu data: US$2.16 per user,” wrote Asay.

To address all of these challenges, Google has spent years trying to make the mobile web apps as fast, useful, easy and seamless as native apps for iOS and Android, and less expensive to boot.

According to Google, a Progressive Web App “uses modern web capabilities to deliver an app-like user experience. They’re reliable, super fast, and engaging, behaving just like an app and thus bringing the best of mobile sites and native applications to users.”

A PWA in layman’s English?

Let me try: If you go to a website that has been set up as a PWA, you don’t even know it. There are cool coding devices called service workers that are storing elements on your device to cut down on loading time when your connection is slow or non-existent. The PWA site can be set up to work and look just like a native app.

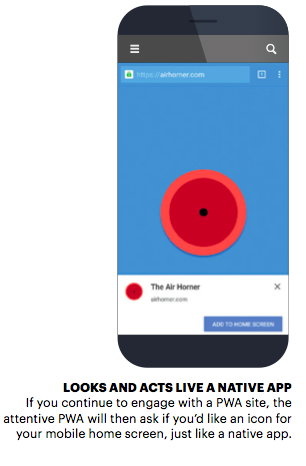

And it’s learning. If you keep visiting the same website, then the browser (Chrome, Firefox, etc.) hosting the PWA will “ask” you if you’d like to get push notifications from the site when important stuff happens.

If you continue to engage with the site, the attentive PWA will then ask if you’d like an icon for your mobile home screen, just like a native app. Presto, an app-like experience without the tedious, time-consuming, often frustrating visit to the app store ending in adding an app to your phone that eats up memory.

“The benefit of a PWA is that you evolve towards the app experience without the user ever having to be pushed towards an app store install, which has notoriously high bounce rates,” Tom Dale, a creator of Ember.js, a leading enterprise JavaScript frame work, told TechRepublic.“The ‘app,’ in other words, sneaks up on the user, giving her what she needs in increments, slowly becoming an app as that app experience is needed,” wrote Adobe’s Asay. “Users don’t have to make a heavy-weight choice upfront and don’t implicitly sign up for something dangerous just by clicking on a link. Sites that want to send you notifications or be on your home screen have to earn that right over time as you use them more and more. They progressively become apps.’”

Hence the term, “progressive” web apps.

“We’re all used to seeing those obnoxious messages when we visit Yelp or some random news source, urging us to install their native apps instead of loading the mobile website,” wrote Alex Russell, Google senior staff software developer, on Quora. “Most of us ignore these nags, because we don’t want to stop what we’re doing just to download an app we’re not even sure about. Progressive Web Apps at least get a chance to ingratiate themselves first. “You have a lot less friction,” Russell says. “And I think that’s really the story here.”

In a nutshell, “the really exciting thing about PWAs: they could make app development less necessary — your mobile website becomes your app,” wrote Peter Wailes, chief software architect at SEO company Builtvisible, on moz.com, “You will only need to develop a single ‘plat- form-agnostic’ version of your app and make it accessible to all potential users, no matter what device they are on,” wrote Antoni Zolciak, inbound marketing manager at tech solutions company InsaneLab on the company blog.

Advocates of PWAs, cite the following attributes as arguments for the ascendancy of PWAs as the primary interface between mobile users and content sites:

FAR LESS EXPENSIVE

“You’re looking at a minimum $100k commitment to build a proper app (usually a lot more),” wrote Eric Elliott, a software engineer for Adobe and author of two programming books, on his own blog. “If you want to cover the gamut with native apps, you can multiply that number almost by three. Instead of writing three different apps, one for An- droid, one for iOS, and one for the web, PWA app makers only need to build one app that works for all three.” (Editor’s note: iOS doesn’t accept service workers yet; more detail below.)

RESPONSIVE

Fit any form factor: desktop, mobile, tablet, or whatever is next.

CONNECTIVITY INDEPENDENT: THEY WORK ONLINE AND OFF

Thanks to our friends, the service workers, PWAs collect and store data, enabling the PWA to function offline or on low-quality networks.

FAMILIAR, APP-LIKE EXPERIENCE

PWAs are designed to mimic native apps, giving users the comfort of a familiar setting while retaining the full functionality of the web with dynamic data and database access. They can be designed to look just like a company’s existing native app and/or website.

EXTREMELY LOW DATA USE

Progressive Web Apps consume 92 per cent less data compared to a native app, allowing them to better address users with slower phones or limited storage, according to Owen Campbell-Moore, product manager at Google.

NO APP STORE SUBMISSIONS, INITIALLY OR FOR UPDATES

The app stores are increasing their regulatory hurdles that apps must clear, making the application and approval process for apps and app upgrades in Google Play, Windows Phone Apps, or Apple’s App Store a tedious and time-consuming process.

FRICTIONLESS REGULAR UPDATES

With PWAs, developers can update the app without submitting it and waiting for approval from one of the app stores, allowing for up- dates at a pace not possible with native apps today. And readers don’t have to download anything to get those updates; they are downloaded automatically when users relaunch the progressive app. And, thanks to the ability of PWAs to use push notifications, media companies can let users know that an update has arrived.

IMPROVED PERFORMANCE

Progressive Web Apps are super fast thanks to the tech caches which can serve text, stylesheets, images and other content instantly.

SAFE

All PWAs must use the popular protocol called HTTPS to ensure secure communication over computer networks and protect the privacy and integrity of the exchanged data.

DISCOVERABLE

Most media companies struggle to stand out among the 5 million available apps on the iOS App Store or Google Play Store. By contrast, PWAs can easily be found by organic or paid-search visitors, giving media companies a much greater chance of converting those visitors into PWA installs.

FAST, EASY INSTALL

Unlike native apps, a PWA does not require installation prior to using it. And also unlike native apps, PWAs don’t suffer the same “install friction” that stops 80 per cent of users who start the download process.

AUTOMATIC PROMPT TO INSTALL THE APP

Several browsers automatically prompt users to install the progressive web app icon after users have visited the PWA more than once. Those browsers send a call to action (CTA) in the browsers themselves, giving the installation request credibility, authority and reliability.

SHARABLE CONTENT; GREATER REACH

Content on a PWA is easily shared via a link compared to content on a native app which cannot be shared. “Like websites, PWAs can be accessed via URLs and are therefore indexable by search engines, meaning it’s possible to find the pages on Google and Bing, for instance,” wrote Mark Pedersen, an app developer at app agency Nodes. “This can be a huge advantage compared to mobile applications where all internal data is just that, internal.”

PUSH NOTICES

One of the most important features of native apps is the ability for media companies to send push notifications out to their app audiences. PWAs also have that ability and it’s turning out to be popular with readers. “Out of all the people downloading a progressive web app, almost 60 per cent gave the PWA permission to publish push notifications,” wrote Pedersen.

For magazine media with e-commerce built into their offerings, a PWA could mean an entirely new entry channel for sales, since push notifications directly displayed on phones are getting read far more often than either email newsletters or status updates on social media, according to Pedersen.

BUSINESS MODEL FREEDOM

“When you’re not in the app store, you’re not limited by the app store rules and you don’t have to pay the app store 30 per cent of sales,” wrote Cloud4’s Grigsby.

APP MAINTENANCE

Maintaining applications for multiple platforms is costly. “In the future, progressive web apps could reduce this cost by providing a single app that works on any platform,” wrote Grigsby.

There’s a lot to like about PWAs.

“With a progressive web app, you visit a URL and immediately get to try the app,” wrote Elliott. “If you continue to use it, you get prompted to install it to your home screen with one click. From that point on, it behaves like a native app. It can work offline, take photos, use WebGL for 3D games, access the GPU for hardware-accelerated processing, record audio, etc… The web platform has grown up. It’s time to take it seriously.”

There is one fly in the ointment, but it may not be a problem for long.

“Ironically, even though Apple pioneered many of the progressive web application technologies, iOS seems to be the only major obstacle to progressive web app adoption,” wrote Elliott in late 2016. “They don’t currently support service workers, and have only hinted at any interest in adding support.”

“Thankfully, there’s a Cordova plugin that adds service worker support to hybrid apps on iOS,” wrote Elliott.

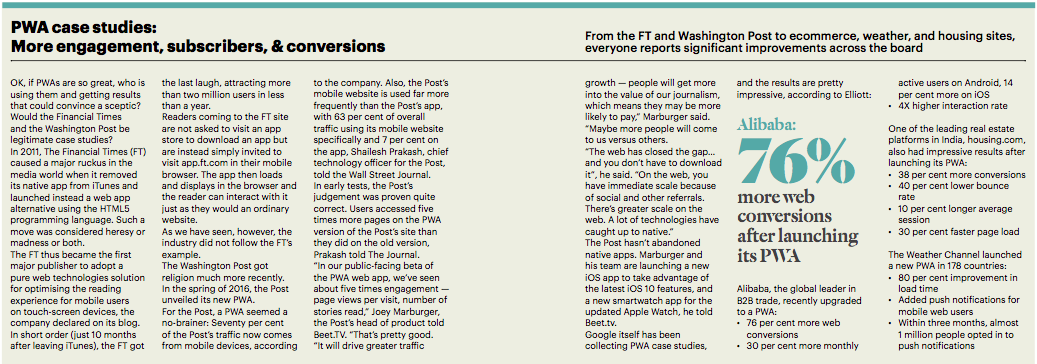

Even without iOS support of service workers, building a PWA can still increase adoption on iOS: AliExpress (Alibaba’s eBay) saw an 82 per cent increase in iOS conversion rate after building a PWA, according to Google.

“If you think the lack of Apple support should hold you back, remember that Android is now 86 per cent of the global mobile OS market,” cautioned Elliott.

Conclusion

A PWA is one of those no-brainers that come along once in a blue moon.

If you already have one or more native apps, maintain them, but build PWAs to capture the top-of-the-funnel users and convert them to the native app.

If you don’t have a native app, go straight to building a PWA.

You won’t regret it.

And I’d hazard a guess that you’ll get many more engaged users, none of whom will ask you why you don’t have a native app in the app store!

This article is one of many chapters published in our book, Innovations in News Media 2017 World Report.